DOI: 10.3726/9781916704459.003.0002

Guiding Question: How do children enter the juvenile justice system?

- Understand how children enter the justice system.

- Understand who enters the system.

- Understand the backstory of children entering the system.

How do kids go from living a regular life as a teenager to entering the justice system? It can happen in three basic ways: children are arrested in the community for a crime, children are referred to the system for a crime, or police are called to the home by parents. Once a child enters the system, they may be detained pending trial or left in the community until trial. Nationally, juvenile justice spans the spectrum from very punitive to restorative. As a country, the United States allows each state to determine independently how to respond to juveniles and to criminal infractions as a whole. As a result, what happens to an offender is very dependent on their age and the state in which they offend. Each state sets the age for treating people as juveniles versus adults, and each state determines where different people are incarcerated. Overall, the United States has a juvenile incarceration rate of three times that of any other developed nation (Widra and Herring, 2021). This chapter will describe the national picture of juvenile justice and dive deeper into four common scenarios of children in the South Carolina juvenile justice system. Each scenario is followed by background information from the literature to situate the reader’s understanding of the issues on a national and state level.

Biology tells us that adolescents are not developmentally prepared to make adult decisions, yet these juveniles are being incarcerated, in many cases as adults (Cavanagh, 2022). It is developmentally appropriate for youth to engage in risky behaviors. Research shows that this phenomenon has an important developmental function: these early risk-taking experiences prepare us for adulthood, leading us to be more willing to take on important new challenges later in life, such as starting a job or leaving home (Human Impact Partners, 2017). Charging youth as adults directly ignores this science of adolescent development. Children undergo two transitions when they are incarcerated as adults: a developmental transition from child to adult and an institutional transition from living in the community to being incarcerated, according to Altschuler and Brash (2004). Juveniles need help to work through both transitions. If there is hope for success, this is the time for intervention. Historically, it has been proven that education and skills training of incarcerated individuals reduces recidivism rates by 13% and is cost effective. Every dollar spent on correctional education saves $5 in three-year reincarceration costs, according to the RAND Corporation’s 2014 annual report.

A student’s time incarcerated is a time to increase their learning and skill development to get them closer to grade level or to the level of entering a career. The youth in the juvenile justice system face many barriers to completing their education while they are held in facilities (and once they are released). Unfortunately, 66% of youth do not return to school after being released from secure custody (Federal Interagency Reentry Council, 2012). We need more proactive programming to prepare our youth to reenter society and meet or exceed community expectations. As RAND (2015) suggests, we cannot afford not to.

What happens to juveniles when they enter the juvenile prison system? In most cases, juveniles receive little education and/or skills training while incarcerated, if any. Their academic and social skills decrease after they are held for committing an offense, putting them at a further disadvantage. Aizer and Doyle (2015) suggest that juvenile incarceration results in significantly lower high school completion rates and higher adult incarceration rates. This should signal that something needs to be done to route juveniles away from the system of incarceration, and, when that is not possible, more resources need to be allocated to those incarcerated.

In South Carolina, the national concerns of high juvenile incarceration, high recidivism, and low educational skills are also apparent. Children held in these state facilities are treated as inmates, much as their adult counterparts are treated, despite their age and developmental stage. Many lawsuits have been filed against the SCDJJ, most recently a civil suit from the ACLU of South Carolina. According to a lawsuit filed in April 2022 in the U.S. District Court, District of South Carolina, children held in SCDJJ facilities are routinely subjected to violence, months-long isolation in solitary confinement, and a lack of meaningful educational or mental health services. These inmates, students, are frequently denied adequate schooling due to overcrowding, lack of staff, and safety issues. When youth are incarcerated, they need intense work in academic and social skills to enable them to return to and succeed in a setting where they were previously unsuccessful. Students entering the system are usually already behind and frequently considered to be of low intelligence and have poor academic achievement (Altschuler and Brash, 2004). They need more help than they had before they were incarcerated, rather than less.

John, a 15-year-old White male, is repeatedly cited and subsequently arrested for selling marijuana near his house. John lives in a neighborhood of low-income houses and families struggling to get by. He is one of many teens who are out late at night and have inconsistent attendance at school. During his arrest, John is found to have a knife in his possession. Given the drug charge, weapon, and his history with police, John is sent to the evaluation center pending sentencing or release. He is transported in a police car in handcuffs to the facility where he is processed in. When he is called to court 20 days later, he explains that he has five siblings and his mom works as many jobs as she can get. John’s mother is having to choose between paying rent and putting food on the table. Despite her work at a fast-food restaurant and other odd jobs, she is unable to provide the necessities for her children. As the oldest, John needs to help feed and meet the basic needs of his siblings. School and other activities are secondary. John’s revelation in court gets some recommendations for food banks and he is sent home on probation, time served.

The USDA defines food insecurity as “limited or uncertain access to adequate food” (USDA, 2023). The two parts of the definition are important to separate out: one is quantity, and the other is quality. Unlimited access to Cheetos is not food security. Without proper nutrition, teens are jeopardizing their physical development (malnutrition, diabetes, obesity, lowered immunity, cardiac disease), education (missed school, delayed brain development, behavior that results in being removed from class), and mental health (anxiety, depression, stress, substance abuse, behavior disorders). Food insecurity does not receive as much attention as generalized poverty but takes a huge toll on teenagers.

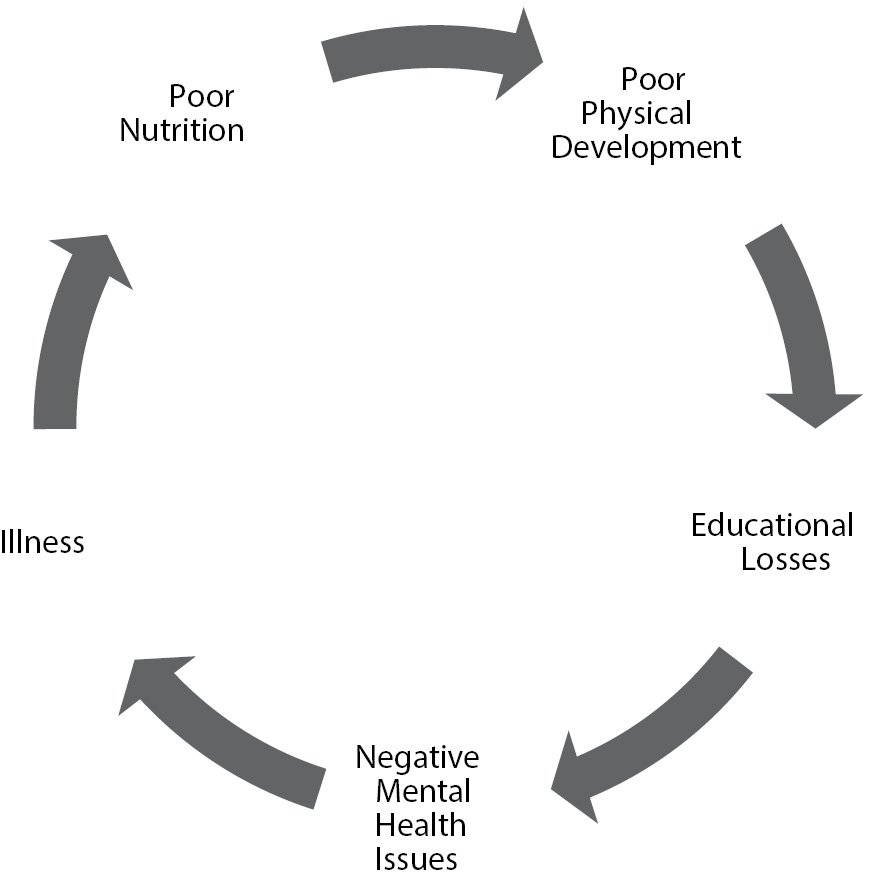

Food insecurity leads to physical developmental issues including diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and many others. Obesity is linked to diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and cancer. The physical impact of food insecurity then leads to negative educational results. Young brains are more vulnerable to the impact of nutrient deficiency than those of adults. According to the Journal of Pediatrics (Cusick and Georgieff, 2016), brain development supported by good nutrition influences positive impulse control, attention, mental health, and social-emotional skills. The cycle starting with poor nutrition from food insecurity can lead to illness and lack of development physically, mentally, and educationally and ends in illness and other negative results (Castle, 2019).

Food insecurity is not just a lack of food, but a lack of safe, nutritious food. This means food that is not spoiled or out of date, food that is healthy, not just cheap junk food. For example, a fast-food hamburger is cheaper than a salad with grilled chicken. The reliance on cheap, poor-quality food is part of the issue (USDA, 2023).

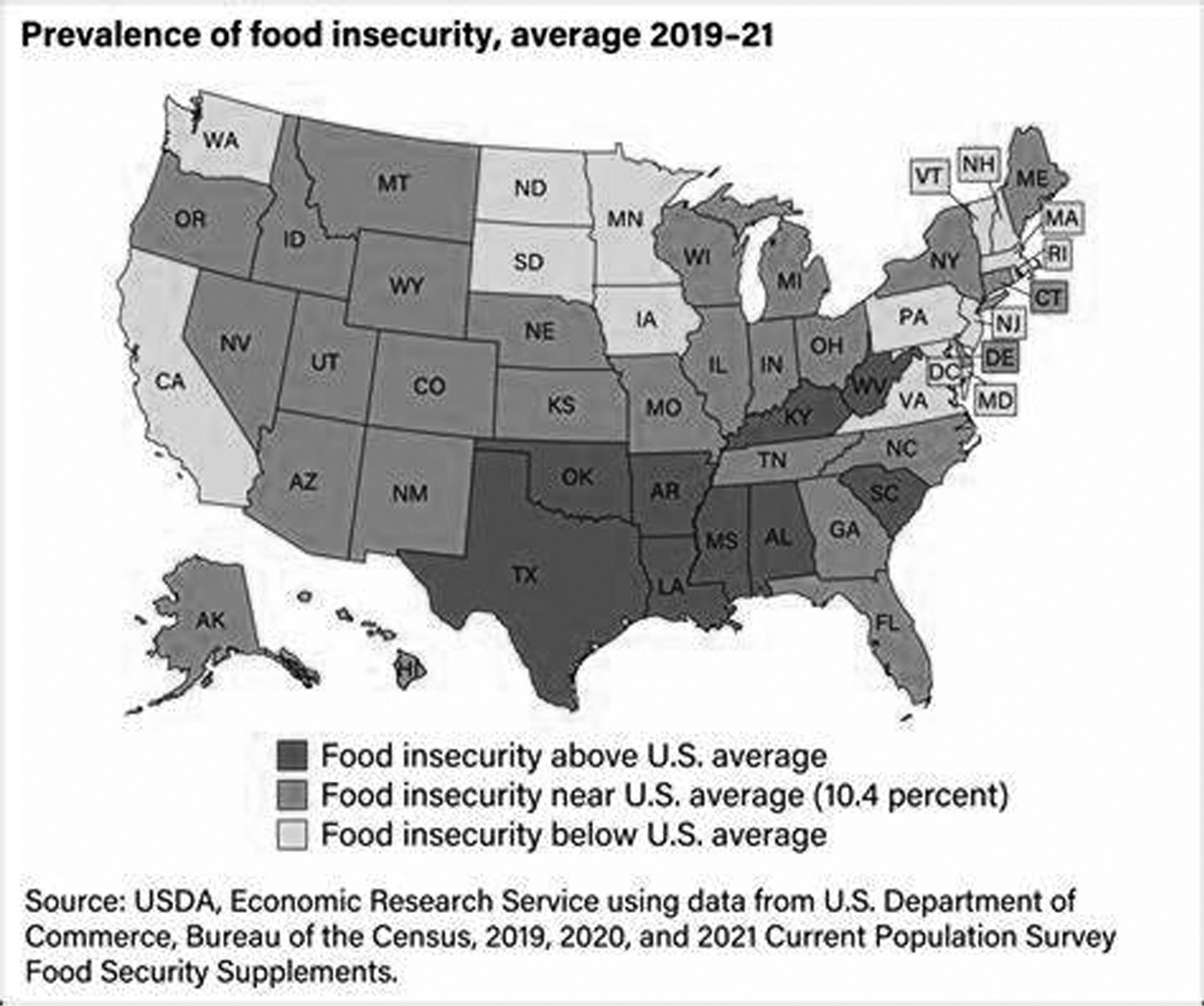

According to the Feeding America report, in 2016, 6.8 million Americans between the ages of 10 and 17 were food insecure, meaning they did not have enough to eat and the threat of running out of food at any time was a reality (Pokin, Scott and Galvez, 2016). According to Coleman-Jenson et al. (2018), approximately 16% of U.S. households are food insecure with limited or uncertain access to safe, nutritious food.

Food insecurity and poverty significantly impact how teens behave. This is a general discussion of food insecurity and teens (not John’s story specifically).

Food-insecure teens who don’t get enough to eat sometimes resort to extreme measures to cope with hunger—from saving school lunches for the weekend or going hungry so younger siblings can eat to stealing or trading sex for money to buy food. (Popkin, Scott and Galvez, 2016, p. 1)

Not all food-insecure teens resort to risky behavior, but teens living with food insecurity and taking on the role of trying to feed younger siblings frequently do resort to criminal activity.

The move to criminal activity comes after teens fail to find legitimate jobs—or legitimate jobs that pay enough to help their families. Teens describe augmenting their minimum-paying jobs starting with smaller crimes such as going through a store’s self-checkout and not scanning all their items. When this is not enough, teens resort to stealing larger items to sell on the street. Many teens take up selling drugs to make ends meet. Teens frequently balance school, work, and drug sales to help feed their families. Many teens don’t give up school because that could get them in trouble with the police, but, ironically, they are selling drugs at school. Research put out by the Partnership to End Addiction frequently recognizes that 60% of high school students can get drugs at school, and marijuana is the most commonly sold drug in U.S. high schools (Salmassi, 2012).

Girls are more likely than boys to resort to selling themselves to earn money for their families. Interviews with teen girls show that they do not consider themselves to be prostitutes; rather, they are trading: “if I had sex with you, you have to buy me dinner tonight … that’s better than taking money because if they take money, they will be labeled a prostitute” (Popkin, Scott and Galvez, 2016, p. 16). Girls actively seek older men who seem to have money to “date” so they can get things such as food, money, jewelry, and so on. Boys were more likely to steal and sell drugs and exchange sex for resources.

From school to the justice system in an hour: a student at Spring Valley High School was asked by a teacher to put her phone away, and she refused. A school administrator asked her to leave the classroom, and she refused. The school resource officer (SRO) was called. Then, in a now-infamous 15-second video taken by other students in the classroom and posted on social media, anyone can see the student get arrested. Heavy.com news outlet and many others reported on the video that shows a White officer grabbing the Black student by the arm as she sits at her desk. The officer asks her to leave the classroom with him, and when she refuses, he pulls on her arm, moving the desk and the girl, and then grabs hold of her shoulder and neck area. As she falls backward, she throws her arm up and hits the officer in the jaw. He turns over the desk, throwing it and the girl, he then drags her toward the door, pulling the desk along with her. Once she is out of the chair, he jumps on top of her to handcuff her. The girl’s lawyer, Todd Rutherford, said she was injured. She has a cast on her arm, and she suffered back and neck injuries, along with a rug burn to her face. According to the attorney, the unnamed girl recently entered foster care after the death of her mother. The 16-year-old student was arrested for disturbing the peace.

Richland County Sheriff, Leon Lott, confirmed in multiple news outlets that charges were not dropped even though he announced that Deputy Fields was put on suspension and later let go. Another student who tried to intervene on the girl’s behalf was also arrested for disturbing the peace.

Another student identified as Tony Robinson told WLTX-TV, “I’ve never seen anything so nasty looking, so sick to the point that other students are turning away.” Robinson described the students as “scared for their lives” and added, “That’s supposed to be someone that’s going to protect us. Not somebody to be scared of.”

In addition, Niya Kenny, another student, got involved when she tried to defend the unnamed girl. This resulted in Kenny being charged with disturbing the school and arrested as well. Kenny told WLTX-TV that Fields was yelling at her when she spoke up to defend her classmate (Cleary, 2021). I was praying out loud for the girl”, Kenny told the news station. “I just couldn’t believe this was happening.” Kenny, 18, was charged with disturbing the school, a misdemeanor, and released on $1,000 bond (Cleary, 2021).

This incident was turned into a larger documentary titled On These Grounds (Simonpillai, 2021) . In the documentary, Vivian Anderson, an advocate for Black girls, led the charge to raise awareness of police impact in schools and created a group called Every Black Girl. She has worked to empower Black girls to speak up and fight against injustice.

Those in favor of police in schools cite the counternarrative Why Meadow Died. Fields attended a session with one of the authors of this book, Max Eden. Fields expressed his opinion that the school-to-prison pipeline was a myth. Eden describes that taking away the power of teachers and SROs is making schools more dangerous in his book. Fields discussed his belief in stopping bad behavior in schools throughout the documentary On These Grounds. Many believe that there is a direct line between being in trouble in school and winding up in prison as an adult. On These Grounds portrays the relationship between race and school discipline.

Richland County has the largest school resource officer (SRO) program in South Carolina SROs are sworn law enforcement officers assigned to a school. Some officers work full-time in one school, while others split their time between school and other duties. They work with school administrators to ensure school safety. It is critical that SROs are trained in child development and understand that children are not tiny adults; rather, they have not fully developed cognitively. Hopefully, SROs are creating relationships with students so they can mentor and support children.

However, placing SROs in schools remains controversial. In 2020, there were an estimated 20,000 SROs in schools (Justice Policy Institute, 2020). Critics, such as the Center for Public Justice, claim that law enforcement in schools is perpetuating the school-to-prison pipeline by making it more likely that children of color are arrested because of police proximity to students. Discipline that should be managed by school officials has become an arrestable offense, and this creates a hostile environment for already at-risk youth. Minor school infractions are introducing students to the justice system, which could stay with them for a lifetime. Nationally, 7% of youth arrests happen at school (Justice Policy Institute, 2020), and many believe these arrests would not have happened if there were no police officers in the school. Critics of SROs think money would better be spent on counselors and other programs.

This quote from the ACLU executive summary on the white paper Bullies in Blue , published in April 2017 (French-Marcelin, 2017), shows the negative impacts of SROs:

Every day in our nation’s schools, children as young as five are charged with “crimes” for everyday misbehavior: throwing a paper airplane, kicking a trashcan, and wearing sagging pants. 2013-14 school year, the most recent year for which statistics are available, schools reported over 223,000 referrals to law enforcement. A 13-year-old Texas boy who attempted to pay for school lunch with a $2 bill that turned out to be fake faced prison time on charges of felony forgery. In Virginia, a middle school student was charged with assault and battery with a weapon for throwing a baby carrot at her teacher. (p. 8)

The criminalization of youth has created schools which are not places of saftey, but places where non criminal behavior can lead to arrest.

Author’s note: As a former assistant principal and principal, I have worked with more than one SRO. My experiences were extremely positive. We worked as part of large administrative teams with clear communication and purpose. My SRO counterparts were able to support me as I made home visits and entered physically dangerous situations. Only in cases in which I would have called law enforcement into the school did the SROs take over; until that point discipline was handled by the school. We had a collective interest in “big picture” safety. The SROs focused on community safety, not minor infractions that could be handled by calling parents or letting administrators use the school conduct policy. We created an environment where kids could make mistakes and make reasonable repairs to their community rather than involving them in the justice system. The SROs with whom I worked engaged students at lunch, coached teams, and supported students in the community. These SROs became trusted adults who worked with me and the students to come up with solutions. The research on SROs is still inconclusive.

Alana calls the police repeatedly because her daughter Tia keeps locking herself in her room. The first few times, the police come and get the girl out of the room and tell her to behave. Alana then decides she wants her daughter charged as an incorrigible youth. On the next call to the police, she tells the police she can’t handle her daughter anymore and she doesn’t want her in her home. The police take Tia to the detention center pending a hearing; this would be an appropriate use of an emergency foster placement, were there an adequate number. In family court several days later, Tia claims she has been locking herself in her room because her mother has been inviting men to the house at night to prostitute herself for drugs. When the house would get busy, men would try to get into Tia’s room. Tia is remanded to Department of Social Services (DSS) custody, which we see in the next story is not always a solution. Tia is not ultimately sentenced to prison time in addition to time in the detention center waiting to go to court.

Child abuse and neglect are underreported in the United States, with neglect being less reported than abuse since it is harder for teachers and other mandated reporters to spot. At least one in seven children has experienced child abuse or neglect in the past year in the United States. In 2020, 1,750 children died of abuse and neglect in the United States (CDC, 2022). Six broad types of neglect have been accepted as common categories, while each state has slightly different definitions of these: physical, medical, environmental, emotional, educational, and inadequate supervision (DePanfilis, 2006).

Physical neglect includes abandonment of the child, refusal to maintain custody of the child, leaving the child in the care of others, hunger, lack of clothing, and other disregard for the child’s safety such as driving intoxicated with the child in the car. Medical neglect is the denial of medical care or the delay in seeking medical care, either yearly preventative care or when the child is sick. Environmental neglect is the failure to protect children from hazards in the local environment and in the home, for example, allowing children to play in the street instead of taking them to a playground. Neighborhood safety is also in this category but rarely addressed since the entire neighborhood would need intervention. Emotional neglect is the lack of affection, spousal abuse of one of the parents in the home, caregivers’ drug and alcohol use, and isolation of the child. Educational neglect includes truancy and inattention to special education needs as a national standard.

The neglect seen in Tia’s story above is inadequate supervision; the girl was left unsupervised in the company of inappropriate adults. This failure to protect a child is clear. It could be added that this example includes environmental neglect given the presence of inappropriate adults and illegal activity in the house.

Seven foster children were arrested at the South Carolina DSS office. The children were charged with aggravated assault by a mob and remanded to DJJ custody. The disturbance occurred just after 8:00 p.m. The children, along with others, have been living in the DSS office. There has been an increase in the number of children sleeping on air mattresses in DSS offices across the state in the last year due to a lack of foster homes. When the end of the day comes, children need to be placed in homes or emergency placements for the night, and these have not been available. These seven children are sleeping on couches or on the floor in sleeping bags until the office opens in the morning. A staff member is left to supervise overnight but clearly could be overwhelmed by the number of displaced children they are supervising. Children removed from their homes are already coming from difficult situations, and now they are left overnight in an office.

In July 2023, foster kids spent a collective 132 nights in state offices (Thomson, 2023). Officials reported a shortage of approximately 2,000 foster homes as of August 2023. The seven teens in this story are being held at the detention center awaiting a court date in family court.

Many of the children unable to be placed in a foster home are suffering from a mental health diagnosis. From April to June 2023, 79% of 109 children sleeping in DSS offices had a confirmed diagnosis (Thompson, 2023). Declining mental health continues to be an issue in foster placement, and there are not enough mental health specialists in the state. The state’s lone 24-hour crisis-stabilization unit is only for adults. Parents are refusing to take their children back from custody due to the unavailability of mental health resources. This leaves children in the system bouncing from placement to placement to office air mattresses, which leads to a further decline in mental health. It is not surprising that these children become agitated while staying overnight in an office with upwards of ten other children in the same situation. South Carolina is in urgent need of foster homes.

Children enter the juvenile justice system in many ways, and several of them are consequently stuck cycling through the system. In Chapter 2, the current system is explained.

1. What have you learned about the juvenile justice system?

2. How could these scenarios have turned out differently?

3. Where do you stand on law enforcement in schools? Why?

1. Watch the documentary On These Grounds and write a reflection.

2. Interview a member of law enforcement who works with juveniles.

3. Watch a documentary such as What Happens When a School Decides to Arrest a Juvenile? (https://youtu.be/AVGgkwmMiac). Write a reflection.

4. Interview an SRO or a school administrator about police in schools.