DOI: 10.3726/9781916704459.003.0005

Guiding Question: What is it like to be inside the juvenile detention system?

- Understand what kids experience.

- Understand what kids are telling adults.

Talking directly to incarcerated children is difficult and could feel coercive to children. To “hear” what kids are thinking and feeling, this chapter relies on adult participants conveying what they have heard or seen from kids, interviews from post-incarcerated youth, and surveys given during E.A.R.N. programming. E.A.R.N. the Right is a nonprofit group that teaches communication skills to students through a six-hour program offered at some DJJ camps and evaluation centers. The adults are able to relay what is happening with children and what children are talking about without upsetting the children in custody. Children’s voice is heard through the adults they trust enough to talk to.

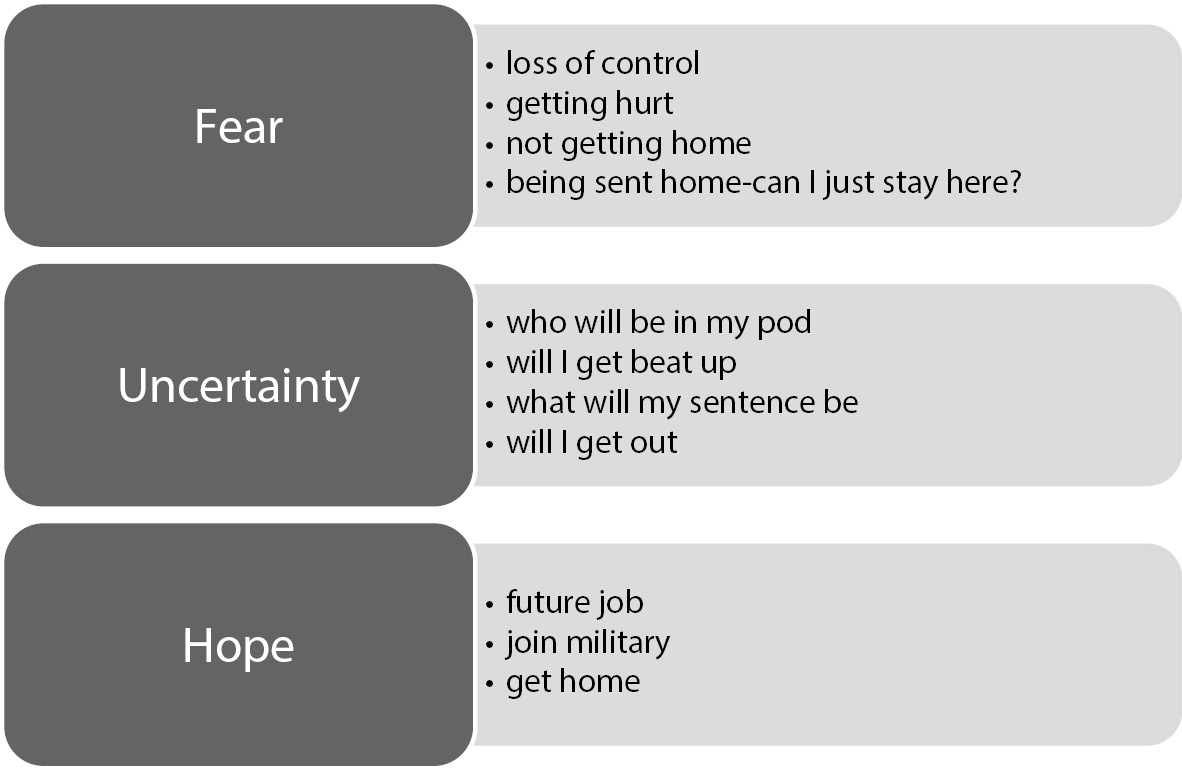

First, it is important to hear kids’ stories from the adults who advocate for them. The interviews from the previous chapter were coded to separate themes from the youth stories that participants had heard. The interviews revealed three themes: fear, uncertainty, and hope for the future.

When a youth enters the system, they start in a state of fear, especially if it is their first time in the system. Children lose all control of their daily lives when incarcerated, and this is worsened by their age since they are unable to make decisions on their own behalf medically, legally, and in all other aspects. These children have no control over where they go, even post-incarceration, since they are still juveniles. Either the state or their parent or guardian will make decisions.

Fear about post-incarceration placement is significant since it is out of the decision-making scope of juveniles. Many children are desperate to get out of the physical system and “go home”. They crave their family and their home. They talk about home-cooked meals, their bed, sleeping safely, and showering at home. Other less-fortunate juveniles are worried about being sent home. The fear they experience inside is more predictable than the fear they face at home. Some youth talk about the inside as a place where “at least” they are getting fed and know where they will wake up in the morning.

Given the volatility of an uncertain future and the lack of children’s developmental growth, it is no surprise that juvenile detention facilities are more volatile than adult prisons. Many of the interviewed adults discussed the volatility of juveniles based on age, brain development, future uncertainty, and general inexperience with the system. Some of the juveniles know they have a determinate sentence and therefore will move to adult prison on their eighteenth birthday, so they have no incentive to behave while in juvenile facilities. This lack of incentive makes the older, more serious offenders more violent and more likely to physically harm other inmates. Physical safety is a huge concern for incarcerated youth. Children tell staff and teachers that they are concerned about getting hurt in the housing pods where there is less supervision.

Uncertainty is linked to the fear; the two are cyclical. The uncertainty of not knowing who will be in the housing pod leads to fear. The housing pod is a pivotal group of peers and affects day-to-day living and safety, when violent or combative children enter a housing pod it creates an increased potential injury to the others. Safety is a major part of the uncertainty.

Youth also worry about their future. Those who have not yet been sentenced worry about what the judge will decide. Where will I be sent? How long will I be there? Where will I go next? When will I get out? The uncertainty is illustrated in the following story. A boy, John (pseudonym), was out for a night with friends. His friends decided to find a rival group’s party and try to get in. When they got to the party, they were not let in, and they left after a fistfight. One of the friends went and got guns from an older sibling. John and his friends carried out a drive-by shooting of the party, injuring party guests. One guest ended up in a long-term coma. John was arrested for being part of a drive-by shooting resulting in injuries. The incident was considered attempted murder. He was convicted and sent to Birchwood for a period. After doing well at Birchwood, John was transitioned to a camp setting as a step in the transition back into the community. One day the deputies arrived at camp and rearrested him. The victim of the shooting, who had been in a coma, died. John’s charge was now murder, and, given his current age, he awaited a new sentence among the adult population.

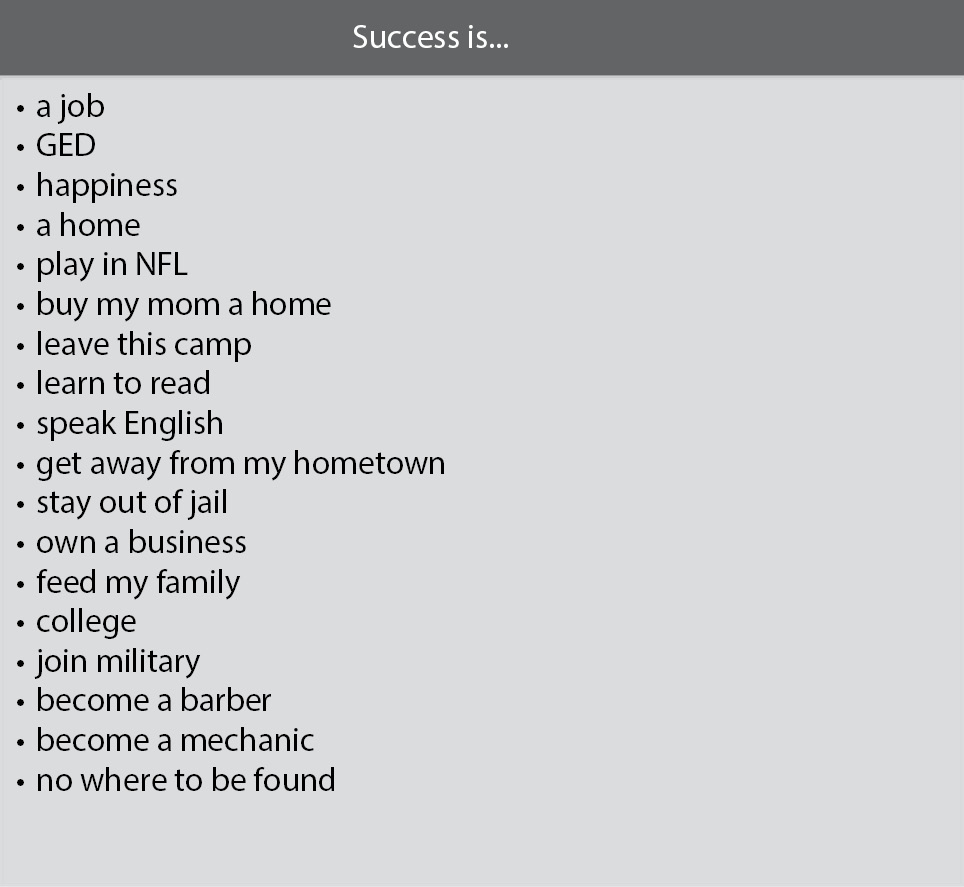

In juxtaposition to the fear and uncertainty, there is also hope among the incarcerated youth. They hope for the time they will get out. Many aspire to join the military or get a professional license such as a CDL or electrician certification. Students who have earned a GED or diploma while incarcerated are thinking about college or a trade. For the students who can keep hope for the future, the adult advocates in their lives hope for their success. Success is universal: not returning to the system.

When students engage in E.A.R.N. the Right, they fill out surveys about their desire to enter the program and how it will help them. The students who can engage in the program are a skewed sample of the entire population within DJJ. These are students who are at a camp or an evaluation center, not at Birchwood (behind the fence). Students who are allowed to attend the program are not disruptive, and they follow the facility rules. While in the program, students are supervised by facility staff.

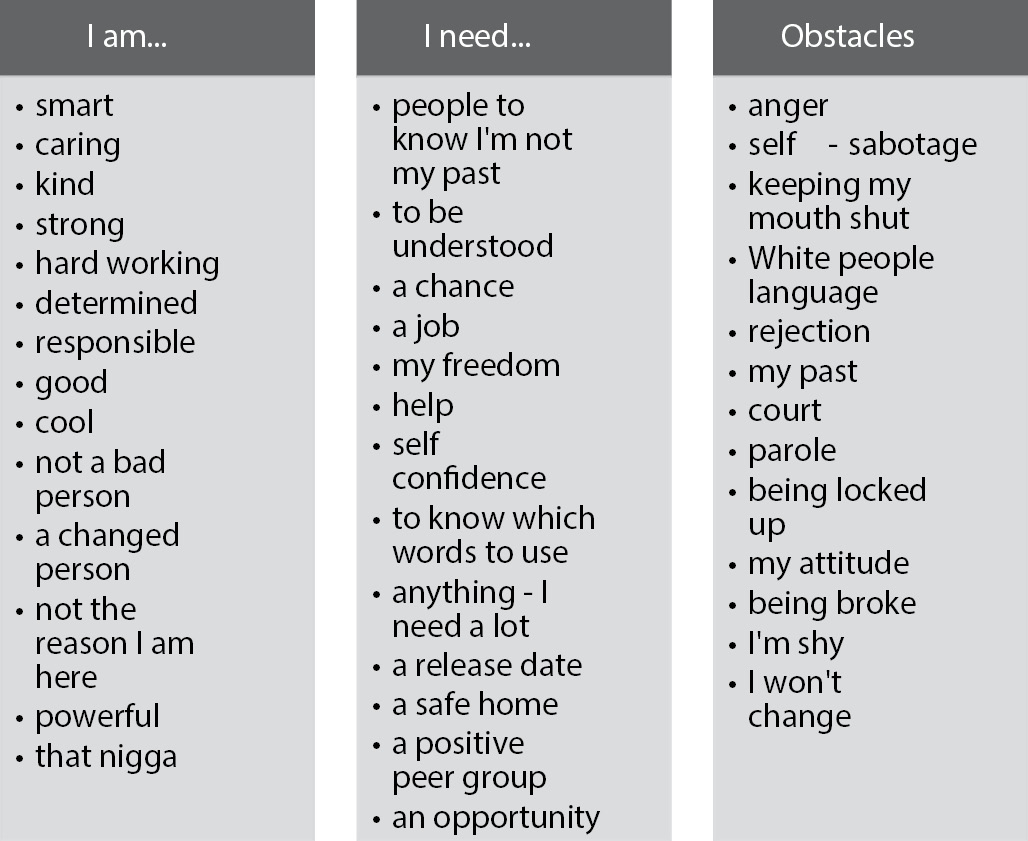

Students seem to be struggling to be heard and be seen for who they are and who they want to be. Three of the most powerful categories of survey responses are around the idea of “I am”, “I need”, and “I want to be”.

Students define themselves as “good”, and there is an overwhelming feeling that they need to show people they are good. This need to prove themselves seems to weigh heavily on how they want to be seen. They often use value-laden words like “strong, kind, powerful, good” to describe what they are trying to be, even though these are not concrete goals. Most students are trying to distance themselves from their mistakes.

Their needs range from general freedom to specifics like a safe home. Students want a chance to change and to improve their lives. Students see themselves as part of their obstacle to success, citing their anger, shyness, past, and inability to change. It is interesting to note that about half of the obstacles cited are self-characteristics, even though many are working to change these qualities. There is a palpable fear that they will not be able to improve.

Parts of the surveys also ask about success: what it is, what it looks like, and how to get it. Students report that…

Success looks different for everyone, and some don’t see it in their future.

Those who choose to work with incarcerated youth talk about their basic beliefs in children’s goodness, building strong relationships with youth, and the obstacles they face when working within the system. They recognize that many children come from inadequate home environments. Children are coming into the system lacking physical recourses, psychological stability, and without clear expectations. Chapter 5 will focus on recommendations for improving outcomes for incarcerated children.

1. What are your reactions to what youth are saying?

2. How do you define success?

3. How do programs like E.A.R.N. the Right impact incarcerated children?

4. What does the recidivism rate say to you?

1. Watch the video “The Making of a Juvenile Delinquent” (hhttps://youtu.be/JWrJTt1I2WQ?si=Xfn2IdD4ryi81R1d). May 2023. or a similar story about the road to detention. How can we change the future of kids and keep them out of the system?

2. Research the recidivism rate in your state. What efforts are being made to reduce it?

3. Watch the video “Incarcerated Children Are Still Children” (https://youtu.be/jjlEpkQYqSw?si=0A03QrKk1Re9jfvb). Review the section on the cost of incarcerating a child for a year versus the cost of a Harvard education (starting at minute 8:00). Based on the statistic quoted that one year in juvenile detention is more expensive than a prestigious four-year degree, including room and board, what would you recommend?