DOI: 10.3726/9781916704459.003.0004

Guiding Questions: Who works with children in the juvenile justice system? Why did they choose this occupation?

- Understand who works with incarcerated children.

- Understand the beliefs of those who work with the children.

- Understand the obstacles faced by these adults.

To examine who works with juveniles at DJJ, the author interviewed more than 20 adults associated with the juvenile justice system in South Carolina. Qualitative interviews were coded, and themes were identified based on the data gathered in the interviews. Participants interviewed were law officers working with juveniles, legal advocates, justice advocates, and DJJ staff or contracted staff working on the education or legal side of the DJJ system as teachers, community outreach and career development staff, and school administrators. These professionals were primarily at the mid-to-late career stage. One participant had been in their position for more than 30 years, having never had a job outside of SCDJJ. More than one participant either had their doctorate or was in the process of earning it. Multiple participants held master’s degrees in education, business, or psychology. Participants describe an overwhelming “calling” to their jobs rather than a need for a job. These are adults who have chosen “to shape the lives of children” despite difficult working conditions, low pay, and safety issues. Everyone interviewed described their “passion for kids” and their desire to help. The adult participants were an overwhelmingly positive, highly educated, and dedicated group of adults.

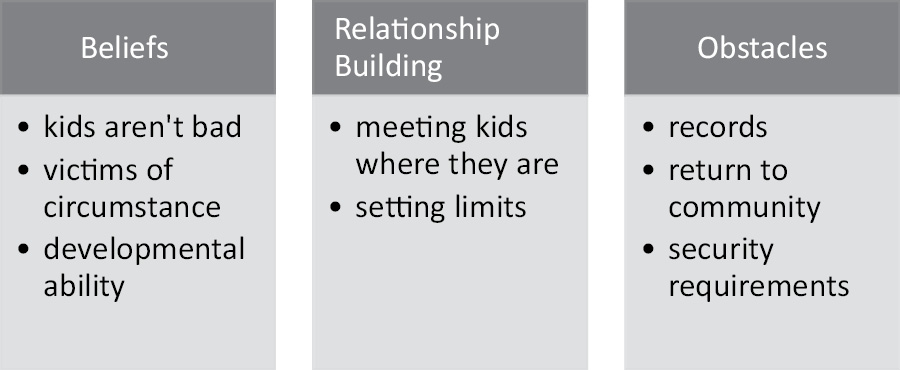

From these interviews, three themes emerged: beliefs, relationship building, and obstacles. Within each theme, several subthemes were common among the participants. Within the theme of beliefs, participants noted that kids aren’t bad, but frequently they are the victims of circumstances and are developmentally unable to make adult decisions. Kids deserve a second chance; staff are overwhelmingly positive about kids’ abilities to turn things around and believe that success is necessary. In the theme of relationship building, participants viewed forming individual relationships with the kids they encounter as key to their ability to create success. Everyone creates relationships in their own way and with their own values. The key is having relationships. Facing obstacles was theme three, and its subthemes spanned the spectrum from not being able to get students’ school records to security requirements to the inability to get students through the educational system despite DJJ being its own school district.

Those interviewed shared an overwhelming belief that kids are not bad. Most conversations started with statements such as …

- “These aren’t bad kids.”

- “These are good kids in bad situations.”

- “There was no way this kid could have made it based on their home situation.”

- “These kids are victims.”

- “These kids are kids who were expected to handle adult problems.”

- “These kids are not developmentally able to make adult choices because they are kids.”

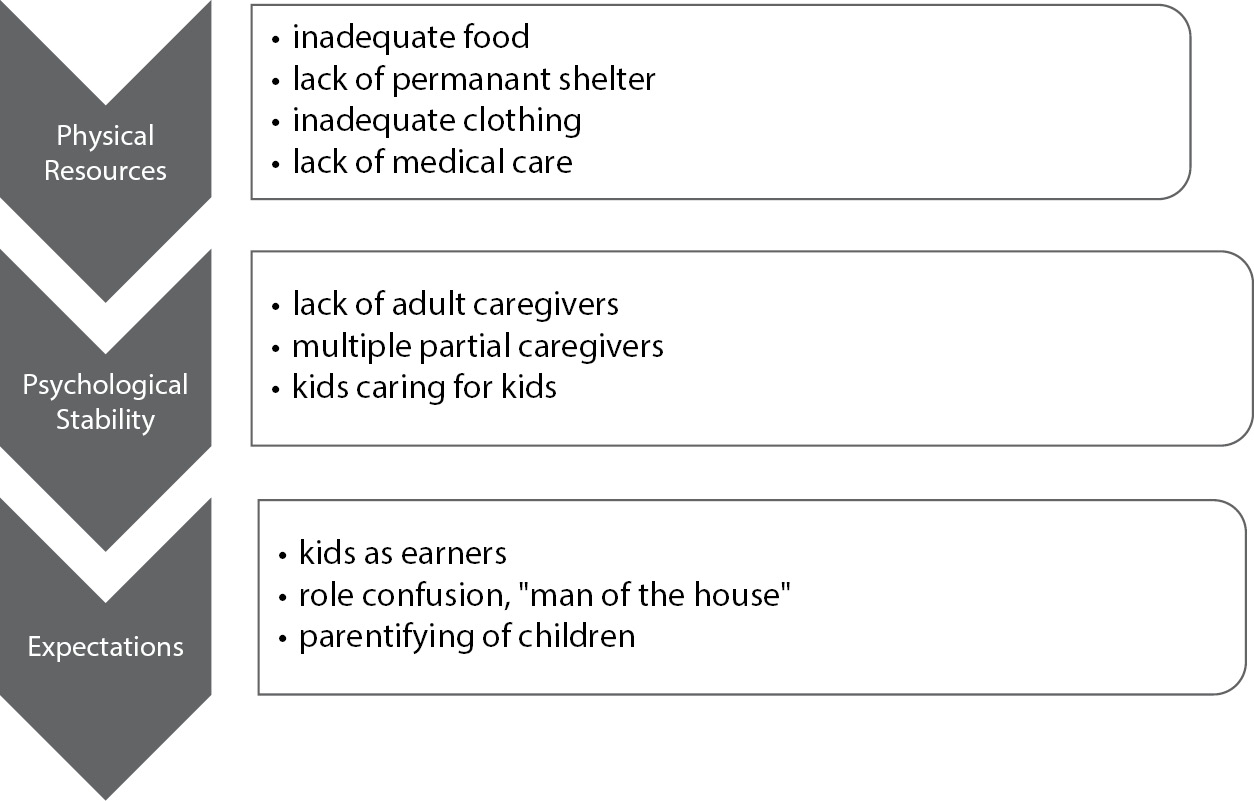

The basic story told by the adults working with incarcerated children is one of an inadequate homelife: insufficient physical resources (food, safe shelter, permanent shelter), ongoing psychological neglect or abuse (no adults regularly caring for children, multiple partial caregivers, kids caring for other kids, abuse, role confusion when boys are asked to be the “man of the house”), and inappropriate expectations (kids being asked to contribute to the family’s earning rather than going to school, caring for siblings). These three factors, combined with adolescent development, led to recurring stories for many kids who are in the system.

Table: Homelife Challenges

Missing tangible resources and generational poverty are the beginning of most of these stories. Generational poverty is a widely used term to describe families that live below the poverty line for two generations or more. Participants told stories about kids living in cars, on friends’ porches, in parks, and couch surfing with their young siblings. This uncertain life led to stealing food or money for needs (medicine, clothes, etc.) and later arrest. Kids frequently engaged in fights to protect themselves or their siblings from predators in these constantly changing living situations. Some entered gangs to gain protection and were arrested for initiation or gang activity once they were in the lifestyle.

Many children in the juvenile system lack psychological stability. Children who come from parents who have faced or are facing their own issues are prevalently involved in psychological abuse or neglect. Some kids were left with “family” while their parents were incarcerated, and sometimes this family was a gang affiliation that indoctrinated the child further into gang life. Other kids were “sold/traded” by parents who were addicts and needed drugs but had no income. According to the South Carolina Human Trafficking Task Force, 399 children were identified as being trafficked in 2022. Still others were born to the victims of domestic abuse, rape, or incest. The children then suffered mistreatment because they reminded the parents of their physical trauma. Children coming from these environments can suffer from post-traumatic stress, psychological and emotional disorders, and attachment disorders (Muller, 2016).

Children as young as 10 to 12 years old are being asked to take on adult responsibilities, and these unrealistic expectations put kids in situations that lead to risky and dangerous behaviors. Many children were described as “having to run a household” at the age of 13 or 14. In girls’ cases, this usually meant taking siblings to school, picking them up from school, foraging for food and feeding siblings, and finding a place to stay for the night. In boys’ cases, this meant keeping siblings “in line”, keeping the family group physically safe, and stealing money or food. This “man of the house” role led to extreme conflict for many boys when the mother took in a boyfriend who then expected the boy (previously the man of the house) to follow his rules. This cycle of going from “man of the house” to “girlfriend’s kid” seemed typical for many of the boys the participants spoke about.

Adolescents are less able than adults to consider the consequences of their actions than plan for the future, control their impulses, and regulate their emotions (Denworth, 2021). Adolescents seek peer approval and respect, which makes them susceptible to peer pressure. Approximately 700,000 U.S. youth are arrested and entered into the juvenile justice system annually. Part of the underlying cause for this arrest rate is that adolescence is a time of increased risk-taking, including illegal behavior (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2020).

Considering the inadequate home life and the children’s lack of full development, participants expressed that these kids need a second chance. There is a clear delineation in the minds of participants between second chances and letting kids “get away with their crimes”. Not one participant expressed a desire to ignore the crime and some form of consequence. It was the type of consequence that was often discussed. Most participants believed that kids getting into trouble need education and mentoring rather than prison. Prevention programs were talked about frequently—programs designed to catch these kids before they made a big mistake. Kids behind the fence were likely to spend 34 to 64 months in juvenile prison, and many were sent directly to adult prison on their eighteenth birthday. This long-term incarceration is not rehabilitative; it is institutionalizing kids and making it harder for them to return to the community with any degree of success—if they ever get the opportunity. Among participants, there is a belief that with resources and education, kids can make a change for the better. Participants agreed that to change their trajectory, kids need literacy skills, career skills, mental health counseling, and in most cases a fresh start in a new community with positive adult mentors.

Everyone who was interviewed talked about creating relationships with kids. One administrator talked about inviting each child into their office and asking about them, their interests, and their goals. Forming relationships in a locked facility poses new challenges, though. The administrator who met with each child realized quickly that kids had no access to pens while incarcerated. In the administrator’s office, kids kept touching and taking pens. The administrator had to call security before the kids went back to their pods to be sure they had not taken any pens, which are considered contraband. The importance of taking individual time with kids was a universal theme. Participants talked about getting to know individual kids and their needs. Working with families to create pathways after incarceration was also mentioned often.

One administrator talked about trying to find an aunt or uncle in another part of the state so the child could start fresh with no gang obligations. Sending the boy home to his “old” situation would be pointless. Gang members would grab him within a block of prison, and he would be back in the life, with no choices, no options. Much of the recidivism rate comes down to a family’s ability to get kids out of the situation they were in before incarceration. Had the family been able to move, they often would have done it prior. Families want the best for their kids, but many times they are not able to provide it because of the circumstances they were brought into, and this speaks to intergenerational poverty.

Meeting students where they are is a common theme. Children misbehave in school when they can’t perform academically, which leads to them being removed from class and beginning the school-to-prison pipeline. Frequently, students are referred to DJJ for school fights, which can lead to third-degree assault charges. Once the child is referred to DJJ, they can be expelled from school, removing the problem from the school district.

Students often arrive at DJJ “overage and under credit”. This means that they have failed classes or have not been in school for an extended period. The average age of students entering DJJ is 16, approximately juniors, and the average number of credits they enter with is 5. The number of credits to graduate in South Carolina is 24, so at the end of ninth grade, students should have at least 6 credits at the average age of 14 to 15, and they should have 18 credits by the end of junior year. In addition, many students arrive with unmet federally required special education plans, both Section 504 and individualized education plan (IEP) requirements, meaning that, by federal law, they are entitled to receive educational services they have not been receiving. Students with 504s and IEPs have educational needs associated with conditions spanning from ADHD to autism. Federal law, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), dictates that students receive services that most of these students referred to DJJ have not been receiving. While this is an obstacle, it is also a relationship-building moment. Rather than focusing on what has not been done and whose fault it is, interview participants see this as an opportunity to meet students where they are and build from there.

Building relationships is not just reaching kids and helping them where they are, it is reasonably setting appropriate limits. Multiple staff talked about caring enough to set limits. Kids know when you are just giving them a pass and letting them run wild because it takes too much energy to set limits and deal with the pushback. One staff member said, “Just letting kids do anything is a cop-out. They know you just don’t care enough to deal with them.” This approach to putting in the time to set appropriate limits speaks to relationship building because it helps kids feel cared for and important enough for an adult’s time. Kids respect adults who take the time to earn respect and set limits. For example, one staff member talked about making kids earn privileges through a bracelet system at one DJJ camp. The bracelets are colored and show what level of privilege each kid has. It is hard to take away privileges because kids get angry and frustrated. But, if kids are disrespectful or do not complete a task and they lose their level of privilege, this consequence tells kids, “I care enough to set limits.”

The relationship building does not end at the door; DJJ has a policy of putting eyes on kids within 48 hours. Rather than send kids out with the attitude of “We are done with you”, they say, “We will see you in 48 hours—you are still ours.” This message of continued care and expectations is meant to carry over to their time, post-incarceration, in the community. Unfortunately, kids are going out into unsupervised and volatile situations, and they often return to DJJ or adult prison. The recidivism rate is 34.2% according to the DJJ Data Resource Guide 2022–2023.

In addition to recidivism rates, participants noted three main obstacles: lack of school records, inability to return students to community schools, and security requirements. All three challenges lead to difficulties in delivering free and appropriate education as mandated by federal law (Free and Appropriate Public Education). As an accredited school system, DJJ is held to the same standards as all other local schools despite their special circumstances.

When students enter the DJJ system, it is frequently difficult to track down their previous educational records. Many students have not been attending school with any regularity since middle school, making it difficult to locate their last school. When records are obtained, they often show low earned credit and special education plans that are incomplete or out of date. Previous schools have been unable to provide the legally mandated services necessary since students have not been in school, which immediately puts DJJ out of federal compliance. Starting out of compliance puts DJJ at a huge disadvantage in getting kids back on track. For example, if a student who was on an IEP enters DJJ, they are entitled to the services laid out in the plan. If the plan is out of date, a new IEP needs to be called and new evaluations done. Students must receive the services called for in the new IEP, such as 60 minutes a day of individual reading instruction, untimed tests, and having all tests read aloud to them. This is not unusual accommodation but requires a greater effort in a secure facility. As noted in obstacle three below, security takes priority over education.

A second obstacle faced by incarcerated kids is their inability to return to public school. In South Carolina, when kids are involved with the DJJ system, they must wait 365 days to return to public school. According to S.C. law 59-63-210, schools can expel students for any crime. An arrest alone can lead to expulsion, and if a child is incarcerated, the 365-day period for potential readmission begins upon their release. In addition to denying students access to education, this sends the message that they are not welcome back in the community. One example of this was a student who, after two and a half years of incarceration, had earned all but 12 credits toward a high school diploma. He was not allowed back in his home public school for one calendar year (365 days). His crime was committed in the community, not in the school; he had no recorded behavior issues in school; and he had received straight As until being incarcerated. The only way to get the boy a diploma was for DJJ to create an online program for him so he could earn his last credits. He completed his degree from a neighboring state in the custody of his grandmother. He started a four-year college as a residential student within months of earning his diploma, and he is doing well. (This student will remain anonymous.)

Security requirements are perhaps the biggest set of obstacles faced by the DJJ educational staff. Despite the legal obligation to provide education and meet special education law service requirements, security takes precedence at a secure facility. The movement of kids determines how education is delivered. If there is tension between two pods, kids in those pods cannot go to the school section of the building together. Thus, their time in school may be cut in half, with each pod taking half of the day. Since pods can’t pass in the building, there is lost time between securing groups.

If there are not enough security officers to move kids who are considered dangerous, then the educators need to go to the kids’ pod to teach. Teaching in the pod does not offer the same security for staff that teaching in the school section does. Teaching in the pod is equivalent to teaching a student in their own home, in that the students know the surroundings and could have hidden weapons. The climate while teaching in the pod is also different since you are in the kids’ “homes” rather than the teacher’s classroom. The physical design of the pod also eliminates safety measures for staff. The tables are bolted in the middle of the common room, so teachers cannot have their backs to the wall and cannot arrange furniture to ensure that kids are looking at the walls so they cannot communicate with each other. The teacher cannot easily see what each student is doing. In addition, the pod common areas accommodate more students than the smaller classrooms do, making it harder to provide physical safety to educators. In the school setting, there are fewer students, smaller spaces that can be locked down, more adults, and, in some cases, part of a rapid response team is stationed nearby.

Another challenge for education staff is teaching students in isolation. When a student is put into isolation for behavioral issues, they are still legally entitled to receive education services. In the case of a student with an IEP that says they need 60 minutes of direct instruction in reading, a teacher must go to isolation and provide 60 minutes of direct instruction; work cannot just be sent to the student in isolation. Sending work to a student in isolation creates security issues since students are not allowed to have basic school items without direct supervision. This tension between security and education creates a complicated system. The system itself becomes an obstacle to educating children who, for the most part, entered the system already behind and disengaged.

Despite the obstacles, the DJJ school superintendent works from a belief that “Success is the only option.” Failing will only send kids back to the community even more unprepared to succeed. To incarcerate and thereby institutionalize a child and then send them back to the place where they already failed, with no new skills, is dooming them to increasingly worse outcomes. The only way to change the cycle of incarceration is to educate children.

Those who choose to work with incarcerated youth talk about their basic beliefs in children’s underlying good qualities, building strong relationships with youth, and the obstacles they face when working within the system. These educators recognize that many of these children come from an inadequate home life. Children are coming into the system lacking physical resources, psychological stability, and clear expectations. Chapter 4 will examine what it is like to be incarcerated.

1. As a nation, we incarcerate more youth than any other developed country. Why?

2. Why are relationships the common denominator in creating success within the system?

3. How do we keep youth from being incarcerated?

1. Research the school-to-prison pipeline and write an op-ed for a local paper.

2. Watch the video on mass incarceration and reflect on your reaction to the statistics.

3. Research resources for teens in your state. Write an article or flier to help teens in need find the right resources.