DOI: 10.3726/9781916985353.003.0001

Human beings have always moved, not all human beings and not all the time, but it is as natural for humans to move as it is for them to be sedentary. Looking across millennia, that movement was often driven by necessity—the need to find food, hospitable lands for crops and livestock, markets for goods, and safety from conflict and persecution. This is particularly true for the Hazara people of Afghanistan and so we hope that this book will illustrate migration experiences common to peoples across the globe. Although we consider Hazarajat, the central area of Afghanistan, our ancestral home, over centuries Hazaras have been forced to leave and to return to Afghanistan.

Mobility and immobility, both chosen and forced, are equally part of our history, a history that is only now being written, and written by Hazara scholars. This is important as, until recently, the history of Afghanistan has been written either by non-Afghans or by dominant groups in Afghanistan that do not include the Hazara. For us, this book is an act of resistance to the discrimination we face. Migration is not just the act of a victim—it is people deciding to resist racialization and victimisation by seeking out places where they can achieve their full potential.

The authors of this book are Afghan scholars who have experienced migration and exile. We are all Hazara and have all grown up in Iran. Atefeh Kazemi is a PhD student in anthropology at McGill University, Montreal; Khadija Abbasi is a Teaching Fellow at SOAS, and currently in Manila and wrote her PhD at the Geneva Graduate Institute on the experiences of young transnational Hazaras; Reza Hussaini is a researcher, currently doing his PhD at City, University of London, but now in Sacramento; Abdullah Mohammadi is an M.A. graduate in Demography from the University of Tehran and currently works for the Mixed Migration Centre, and lives in Stockholm. Khadija has been through the UK asylum system, was granted refugee status, and now has British citizenship. Abdullah and Reza were evacuated from Kabul in August 2021. Reza and his family went first to Poland before being brought to the UK as he had a student visa. They then moved to the US. Atefeh was the last to leave Iran in August 2024.

We belong to a small but growing community of Hazara scholars who are adapting to academia in exile. Within this community, working across a range of disciplines and on a wide variety of topics, a subcommunity is focused on analysing the experiences and history of our people, and as we will show, migration plays a central role in that history. Although belonging to a minority that has experienced discrimination and persecution, and having experienced racism ourselves, we recognize that we four are privileged. Most Hazaras, including our parents, have not had access to higher education or white-collar jobs. Fewer still have managed to travel beyond the countries neighbouring Afghanistan. Our upward social mobility is recent, and we have all either shared or witnessed the restrictions experienced by those who have not had our opportunities.

Many Hazaras are migrants by birth, born in exile but with no access to the citizenship of our birthplaces when those birthplaces are Iran or Pakistan, condemned to die as migrants even if we never leave those countries. We have been labour migrants for decades, often highly skilled but condemned to unskilled labour. We have moved back and forth across neighbouring borders, shifting between legal and social categories—each of us writing here has been at different times, (and sometimes simultaneously) students, workers, refugees, asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, or returned migrants. We have ‘returned’ to Afghanistan but been unable to return to our village or province, and so remain displaced within Afghanistan.

The stories here illustrate this complexity. They overlap in places as we share some similar experiences. In the rest of this chapter, we provide the context and history necessary to understand each of the stories.

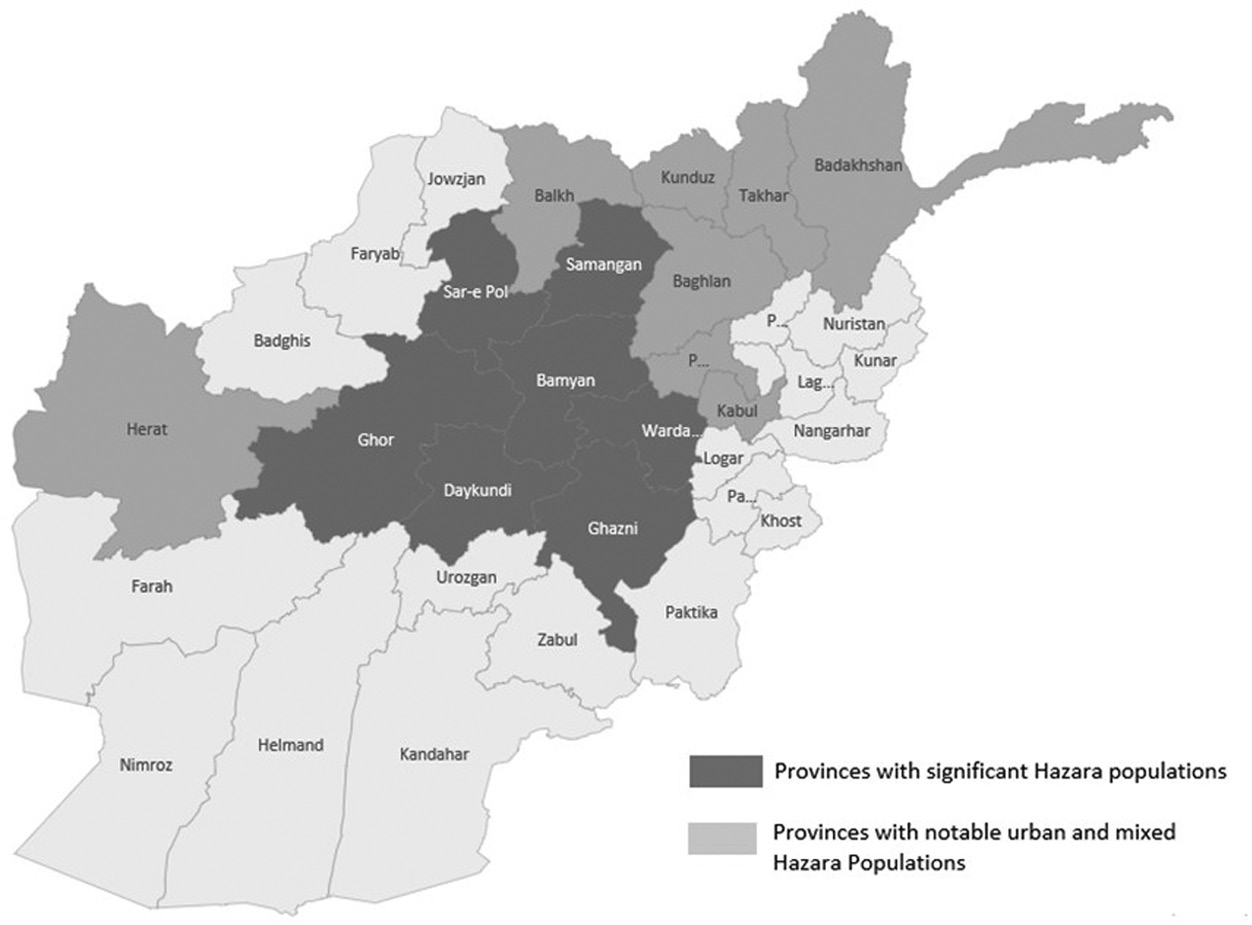

Today, the Hazara can be found in many Afghan provinces, and there are significant populations of Hazaras in Kabul, Herat, and Mazar, but our homeland is regarded as Hazarajat in central Afghanistan. Hazarajat today includes the provinces of Bamiyan and Daikundi, and several adjacent districts in the provinces of Ghazni, Uruzgan, Wardak, Parwan, Baghlan, Samangan and Sar-e Pul. Migration has long been a survival strategy for Afghans (Monsutti, 2005), including Hazaras, though there is also a population of Hazaras, especially in rural areas of Afghanistan like Bamiyan, who have never moved. But all of us, within our family circles, have relatives who have left the country, in most cases due to poverty or persecution, and more recently, prolonged drought in Hazarajat drove thousands to leave for the cities. To understand the forced migration of the Hazaras, we outline the history of Hazaras in Afghan society, which has been a history of persecution, flight and resistance. This history shows clearly that academic categories cannot capture the complexity of forced migration.

Map of Afghanistan showing provinces, ethnic spread and neighbouring states

There is no majority ethnic group in Afghanistan, but the largest minority groups are the Pashtuns, Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Hazaras. There has not been a complete census in Afghanistan since 1979, so we only have rough estimates of a population that has been marked by high birth rates, high mortality, and high migration. There are different estimates that suggest the Pashtuns make up 40–47 per cent of the population, Tajiks 12–27 per cent, and Uzbeks approximately 9 per cent, with other ethnicities, such as Turkmen, Aimak, and Balouch, each accounting for less than 5 per cent. Today, the Hazaras make up about 20 per cent of the population of Afghanistan but before the genocide, (see below) we were the largest ethnic group in Afghanistan (Mousavi, 2018). These populations are not spread evenly across the country, and some provinces are dominated by one ethnic group. In our case, these were the central provinces of Afghanistan, but as we show below, our position in Hazarajat has been undermined.

Hazaras are physically distinct from Afghanistan’s other ethnic groups (though we are physically similar to Uzbeks and Turkmen), with features more usually found in East Asia. We are often racialized based on our physiognomy, which makes it easy to identify and target us, not just in Afghanistan, but also in Iran and Pakistan where most Hazaras have sought refuge. We have often been subjected to racialized mockery and stereotyping, including derogatory remarks about our physical appearance or perceived differences in cultural practices, which have served to marginalize and dehumanize us. Khadija was once asked by a classmate if she could see well with her ‘narrow’ eyes. Our physical features have been intertwined with racial assumptions made about us—that we are fit only for physical labour, that we are incapable of intellectual labour, and undeserving of autonomy and power, such that Hazaras in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan are treated differently. This racialization, and the racism it engenders and justifies, is a theme that we explore below and in our individual chapters. Schuster (2010) has argued that migration and racism are intimately linked, and our experience is a testament to that linkage.

Most other ethnic groups, including the dominant Pashtuns, belong to the Sunni branch of Islam, while Hazaras are Shia, and considered Rafizi (heretics), an accusation used even today to justify our persecution in Afghanistan. A minority of Hazaras belong to the Ismaili sect, and some are Sunni, but whatever our religion, we stand out physically and are easy targets. However, the precarious position occupied by the Hazaras today can be traced back to the actions of one person in particular. In the nineteenth century, we accounted for nearly two-thirds of the population (Minority Rights Group International, 2008). There had been earlier tensions between Hazaras and Pashtuns; then with the approval and support of the British government, Abdur Rahman Khan (1880–1901), ruler of Afghanistan, set out to Pashtunise Afghanistan by confiscating land from non-Pashtuns and settling Pashtuns across the country (Bleuer, 2012).

As noted by Bleuer, ‘since Abdur Rahman’s rise to power, almost every Afghan ruler until 1979 had a policy of attempting to “homogenise” the peoples of Afghanistan. As part of this process …[of] “Pashtunisation,” the Afghan government used Pashtun nationalist ideology, land confiscation, discriminatory taxation policies, and forced resettlement that favoured the Pashtuns’ (2012, 70). Abdur Rahman Khan moved all ethnic groups, including Pashtuns, around the country to consolidate his power and create Pashtun domination in strategic areas. In Hazarajat, parts of which had been independent, this Pashtunising policy alongside heavy taxes, sectarian conflict, corruption, and violence of the government forces led to a rebellion in 1892.

Abdur Rahman Khan declared jihad against the Shias and sent a large army (supported by British military advisers) to put down the rebellion. They captured Urozgān, where the rebellion originated, and massacred the local population: ‘thousands of Hazara men, women, and children were sold as slaves in the markets of Kabul and Qandahar, while numerous towers of human heads were made from the defeated rebels as a warning to others who might challenge the rule of the Amir’ (Mousavi, 1998, cited by Monsutti, 2003). Between 1888 and 1893, more than half of the Hazara population was massacred or fled to neighbouring countries and farther afield and their lands were confiscated, and distributed among non-Hazaras (Mousavi, 2018; Ibrahimi, 2017). The memory of these events and the massacres that have followed, which amounted to a genocide, are a source of ongoing trauma for the Hazara people. It has coloured our relationship with a Pashtun-dominated Afghan state that has continued to single us out for harassment and persecution, even as relations with individual members of the dominant minorities have sometimes been supportive and warm.

When distinctions are made between political refugees and economic or labour migrants, it is important to understand that such distinctions do not make sense for Hazaras (and many other groups) when discrimination and persecution have economic consequences. The poverty driving Hazaras to seek work in Iran was a direct result of discrimination and persecution. The grant of Hazara lands to Pashtun nomads by Abdur Rahman Khan meant that the Hazaras who stayed often became tenants on their own land. Later, attempts were made to impose discriminatory taxes on Hazaras. Both of these strategies have returned under the second Taliban regime. The enforced impoverishment of Hazara people obliged many to become seasonal migrants to Kabul, Herat, and Mazar, and to Mashhad in Iran and Quetta in Pakistan. Hazaras worked as day labourers in construction or as porters in the markets, where once again racialization by the host states and societies confined us to particular areas and occupations, as Atefeh shows in Chapter 3. Refugees need to work to survive and support their families, but this is often used as an excuse to label us economic migrants, thereby exempting us from the protection that refugee status might afford us (Schuster, 2016).

The forced displacement of Hazaras (and other Afghans) accelerated first due to the severe drought of 1978, and then the Soviet intervention in 1979, which led to a decade of conflict between the Soviet forces and the Afghan resistance fighters or Mujahedin (Kakar 1995). We Hazaras are not a homogeneous group; some of us supported the communist government and others the Mujahedin . Much of the fighting in Hazarajat was between different Hazara groups (Ibrahimi, 2017). In June 1979, following an unarmed uprising by Shia in the Chindawol area of Kabul, the Communist government launched an attack. Over two days, many were killed, while others were taken away and their deaths were only confirmed by a Dutch War Crimes Investigation years later in 2012.

It is estimated that 1.5 million Afghans died in that decade and millions fled to Iran and Pakistan, though a few found their way to other countries, including Britain and Germany. Hazaras mostly fled to places with already existing Hazara communities, such as Mashhad in Iran and Quetta in Pakistan. Up until this point, migration outside the country had mostly been by men, with families left behind in Afghanistan (Hussaini et al., 2021). But the war between the Soviets and the Mujahedin saw whole families, and in some cases villages, displaced. Although Hazaratown, a Hazara ghetto in Quetta, expanded at this time, at least half of those Afghans who went to Pakistan were confined to refugee camps, especially around Peshawar.

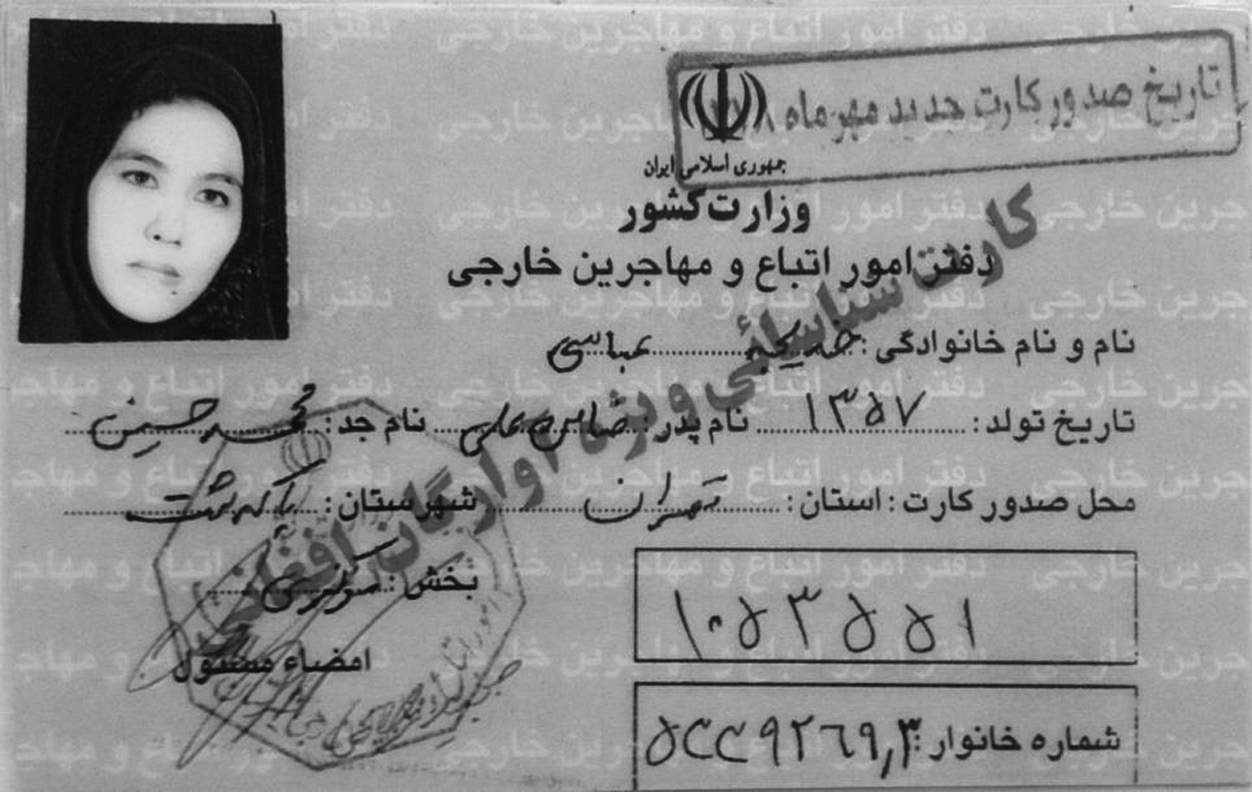

In Iran, the situation was different. Ayatollah Khomeini, who had just taken over leadership of Iran, welcomed Shia refugees from the Soviet occupiers as Muhajir, religious refugees fleeing what was seen as a Soviet attack on Islamic ways of life. However, although some Afghans in Iran are recognised as refugees by UNHCR, the Iranian Republic has never recognised us as refugees according to the 1951 Convention, to which it is a signatory. The concept of Hijrat initially ensured that as Shias in Iran we could rely on the religious duties of our hosts to protect those who had fled for religious reasons (Safri, 2011). As noted by Safri, ‘by describing the Afghans as refugees who struggled to maintain religious faith in the face of a Soviet campaign seeking its eradication, both Pakistan and Iran simultaneously positioned themselves as performing a righteous function’ (2011: 589). Although Iran had signed the Geneva Convention and the New York Protocol, the government chose to designate Afghans as Muhajir, rather than refugees, giving them Blue Cards (identity cards).

Most Iranian scholars (Adelkhah and Olszewska, 2007; Abbasi-Shavazi et al., 2008; Vossughi and Mohseni, 2016) emphasise the generous welcome given to Afghan refugees, citing the words of Ayatollah Khomeini ‘Islam has no borders’, the social benefits Afghans were allowed to access, such as subsidised health care and free primary and secondary education, and the economic costs to the state: 1.5 million refugees, mostly Hazaras, were allowed to settle in Iranian cities, including Tehran, Mashhad, Isfahan, and Qom, though since then the number of zones forbidden to us has increased to 16 provinces, and many cities. The restrictions imposed on us within cities have trapped us in ghettos such as Golshahr in Mashhad, Pakdasht in Tehran, Shahr Qaem in Qom, or Zeinabiyye in Isfahan. In the third chapter, Atefeh focuses on the collective experience of Hazara youth growing up in Golshahr, most of whom are Iran-born, and explores how they perceive themselves as muhajirs in Iran, where the term ‘muhajir’ was stripped of its initial religious connotation by the 1990s.

Hazaras growing up in Iran emphasise the economic contribution we made to different sectors, which explains that early welcome. The discovery of oil in Iran (and in the Gulf States) created a massive demand for labour, in particular manual labour (Safri, 2011). Safri (2011) and Monsutti (2008) both point out that Afghans had to apply for work permits that only allowed them to work in mines, brick factories, and construction. We responded to labour shortages because we were not confined to camps but were self-settled around the country, often following the demand for labour. Although economic changes in Iran led to an economic downturn and increased unemployment, Hazara men were welcomed into the army, where we fought alongside Iranians in the Iran-Iraq war (1980–1988).

However, the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union, together with the death of Ayatollah Khomeini, saw a shift in the attitude of the Iranian government towards Afghan refugees. There were posters in Afghan neighbourhoods telling us it was time to go ‘home’. The pressure increased as the 1990–1991 Gulf War sent a quarter of the Iraqi population across the border to Iran. Iran was hosting 3 million Afghan and 1.5 million Iraqi refugees, who were less visible than we Hazaras. But it had become impossible for most of us to return to Afghanistan (approximately 600,000 Afghans, not all Hazaras, did return), not least because of the civil war that erupted.

Following the removal of Najibullah, the Communist president of Afghanistan, civil war broke out in 1992. After the Mujahidin (resistance fighters) took power that year, fighting between the different factions broke out. Violent attacks occurred in Kabul between the different forces, killing many Hazaras, including unarmed civilians, and many Hazara women were raped (Ahmad). In February 1993, hundreds of Hazara residents in the Afshar district of West Kabul were massacred by government forces under the direction of Burhanuddin Rabbani and Ahmed Shah Massoud, joined by Abdul Rasul Sayyaf and his Ittehad-i-Islami group. The fighting saw the utter devastation of large areas of Kabul, particularly those inhabited by Hazaras (Afghanistan Justice Report 2005).

Once again, Afghanistan saw the displacement of millions of people, much of it internal, but significant numbers migrating once again to Iran and Pakistan, while some made longer journeys to Europe, Australia, and the US. We also learned at this time that it was not only our neighbours who did not want us—Europe’s asylum policies were becoming more restrictive and new laws were introduced in Britain and Germany.

In spite of factors causing continued displacement within and from Afghanistan, host states increased the pressure on refugees to return. At the same time, during a period of increased unemployment in Iran, the Blue Cards were declared invalid and there was a shift from the term Muhajir to that of Awaregan (displaced person), which did not have the same positive connotation.

Khadija’s Blue Card on which the diagonal line says: The identification card for the Afghan Awaragan

According to Safri (2011: 593), 1.3 million Afghans were repatriated from Iran between 1992 and 1995, despite continuing conflict and insecurity in Afghanistan. This coincided with a more general shift in the mid-1990s, including by UNHCR, from a preference for resettling refugees to one of repatriation, and it was no longer necessary for that repatriation to be voluntary (Chimni, 2004). Instead, it was now the state’s right to decide whether it was safe enough to return refugees to their state of origin. As Chimni points out, states from the Global North had no grounds to criticise states such as Iran or Pakistan who were hosting and repatriating many more refugees than they were, but there was little evidence that they were against this policy, even as more Afghans were leaving in response to the brutality of the Taliban regime (Langenkampf, 2003). The shift towards temporary protection and to keeping refugees in their regions, as well as to ‘imposed return’ (abandoning the ‘voluntary’ element), had serious implications for Afghans, especially after the fall of the Taliban. From this time on, it became extremely difficult for people to seek asylum in the Global North without the help of smugglers, as Abdullah describes in Chapter 2.

The period following the fall of the Taliban regime saw massive changes in Afghanistan: the arrival of foreign armies, thousands of aid workers and NGOs, new opportunities, a continuing conflict, and ebbs and flows of migration in and out of the country. New opportunities, such as access to education and different, more skilled employment opportunities arose for Hazara people. We became increasingly visible as business people, parliamentarians, civil society activists, and in the media. However, we were still subject to discrimination as described by Reza in Chapter 4 and Khadija in Chapter 5 and had often to set up our own schools, universities, businesses, and media companies. For those of us who travelled to Afghanistan from Iran hoping to find a home and end our exile, it was a shock to see how Hazaras were treated in our watan, our homeland. We found ourselves discriminated against not just because of our physical appearance and religion, but because we came with Iranian accents and manners.

Immediately after the US attacks in December 2001, the borders of Afghanistan had been sealed by its neighbours, so that the number of refugees was relatively low—about 200,000—while the number of IDPs soared from 1.2 to 2 million. Most IDPs were in poorly serviced camps, with little access to food or medical support and with no institutional protector similar to UNHCR for refugees (Cohen, 2002). Adding to the IDP population were returnees. Safri (2011) points out that very quickly Afghans were expected to ‘return’ to Afghanistan and those who remained in Iran and Pakistan after the fall of the Taliban were reconstructed as ‘labour’ or ‘undocumented’ migrants instead of refugees. Afghans returned rapidly from Iran and Pakistan—too rapidly according to UNHCR, so that in 2002, the new government was completely overwhelmed, and the country was unable to cope. Within the first two years, more than 5 million people had returned to Afghanistan, but most were unable to return to their homes in rural areas—approximately 50 per cent settled in and around Kabul.

Afghanistan continued to experience instability and insecurity. In December 2009, Obama tried to break the stalemate by ordering a surge in the number of troops, but two years later began to reduce the numbers significantly. 2014 was a difficult year. With the reduction in foreign troops, insecurity had worsened, not helped by the inconclusive presidential elections. US Senator John Kerry visited Kabul and negotiated a power-sharing government with Ashraf Ghani as President and his rival Abdullah Abdullah as Chief Executive of the government. However, negotiations between the two over who would allocate which Ministry contributed to ongoing instability. This had an impact on security and saw international companies and NGOs withdrawing from Afghanistan, which in turn weakened the economy, increased unemployment, and strengthened the Taliban. This period saw increased attacks and casualties.

Internationally, war in Syria was driving millions of refugees northwards, mostly to Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, but also to Europe. When Angela Merkel responded by saying that these arrivals were manageable, Afghans who had found life more and more difficult in neighboring countries sought solutions outside the region. However, Europe’s warm welcome was short-lived, and the reception quickly turned hostile. In March 2016, the EU signed a deal with Turkey, according to which Turkey agreed to prevent Syrians and Afghans from travelling on to Europe in exchange for 3 billion euros in aid and easier access to the EU for Turkish citizens. A few months later, the EU succeeded in bullying the Afghan government into signing the Joint Way Forward by threatening to withhold 1.5 billion euros in development aid (Hussaini and Schuster, 2022). To access the aid, the Afghan government was forced to agree to accept forced returns and prevent ‘illegal’ migration.

In 2017, a new President, Donald Trump, took office in the US and began negotiating with the Taliban, and in February 2020, the US and the Taliban announced the Doha Agreement, under which the US agreed to withdraw all U.S. forces from Afghanistan by May 2021. By the time Biden took office in January 2021 and confirmed the withdrawal of the remaining 2,500 troops, the Taliban were already in control of half of Afghanistan. It was assumed that the Afghanistan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF) would take over responsibility for security, though in reality, it was acknowledged that the Taliban would probably re-take power within a year of withdrawal. Instead, they swept back into power in August, entering Kabul on Sunday, August 15, 2021.

The shock in the capital was profound. In the days before their arrival, people were flooding into the city, ATMs were emptied, and the skies were filled with the clatter of helicopters as foreigners fled. The day the Taliban arrived, tens of thousands of people gathered at the airport hoping to flee. In Chapter 4, Reza describes the trauma of those days. The evacuation was officially completed by the end of August, and people could no longer leave by air.

For those left behind, the situation deteriorated rapidly. Our habitual destinations of Iran and Pakistan closed their borders. The Hazara community, already marginalised and persecuted, faced heightened threats under the Taliban regime. The Taliban’s history of targeting Hazaras for their ethnic and religious identity raised immediate concerns for their safety. As a result, thousands of Hazaras sought refuge in neighbouring countries, primarily Iran and Pakistan, despite the closed borders and perilous journeys. Checkpoints multiplied, and at each one, we were required to hand over bribes, cash, jewellery, or some other valuables. Beatings and sexual harassment were commonplace. The desperation of those fleeing persecution and economic collapse led to significant numbers of undocumented crossings. By early 2022, it was estimated that around 300,000 Afghans, including a large proportion of Hazaras, had fled to Iran. In Pakistan, the influx was smaller but still substantial, with thousands of Hazaras seeking refuge, particularly in areas with existing Hazara communities such as Quetta. Despite mass deportations from those countries, people continue to cross into Iran and Pakistan, driven as much by the collapsing economy as the gender apartheid of the Taliban regime. Once again, we find ourselves in precarious and unstable situations, fearing deportation and fearful for those left behind.

This new phase of displacement of Hazaras, driven by both the immediate threat of violence and the broader economic collapse under the Taliban regime, is a continuation of a long history of forced migration and persecution. The new Taliban regime has done nothing to assure the protection of marginalised groups, and reports of targeted attacks against Hazaras continue to surface.

For the Hazaras who managed to evacuate to Western countries, the challenges are different. Many face difficulties in navigating asylum systems, securing stable housing and employment, and dealing with the psychological trauma of their sudden displacement and the loss of their homeland. Additionally, there is a deep sense of survivor’s guilt among those who have reached safety, coupled with a profound concern for family and friends left behind.

Migration is a norm for many Hazaras, who share experiences of migration for survival, security, marriage, labour and education, and often for a combination of all of these reasons (Monsutti, 2005). It is often seen as a necessary and normal, though painful, experience for both the migrant and those left behind (Aranda, 2007). The impact of migration on Hazaras, individually and collectively, in Afghanistan and in exile has been profound and multi-faceted, impacting every aspect of life from economic opportunities to cultural identities.

While structural barriers, discriminatory policies and limited opportunities in Afghanistan have historically restricted Hazaras to low-paying, unskilled labour, migration has often been the only avenue to escape poverty and provide for families. In host countries like Iran and Pakistan, as well as further afield in Europe and Australia, Hazara migrants frequently take on labour-intensive jobs that local populations are unwilling to perform. While these jobs are often exploitative and low-paying, they offer a lifeline to those who would otherwise face destitution. In countries with more supportive refugee policies, such as in parts of Europe and Australia, Hazara migrants have been able to access education and higher-paying jobs, contributing significantly to their host economies. The remittances sent back home are vital for the survival of families in Afghanistan, where economic opportunities remain scarce. Monsutti (2012) in his book, War and Migration, explains the role of migration and remittances as a survival strategy among Hazaras.

Migration has also deeply affected the social and cultural fabric of the Hazara communities. In host countries, Hazara communities have often formed tight-knit diasporas, maintaining cultural practices and languages while adapting to new environments. These diasporas provide crucial social support networks, helping new arrivals navigate the challenges of settling in a new country. However, migration can also lead to cultural dilution and identity challenges. Younger generations born in host countries may struggle with dual identities, balancing the cultural expectations of their parents with the norms of the society they are growing up in. In Afghanistan, many of the second-generation born in exile have experienced discrimination upon return due to their distinct behaviours and values adopted from host countries. Despite these challenges, the Hazara diaspora has managed to preserve a strong sense of identity and community. Cultural organisations and religious centres play a vital role in this preservation. Literature also plays an important role here.

The psychological toll of forced migration on the Hazaras, especially among those evacuated in August 2021, cannot be overstated. The trauma of displacement, the experience of violence and persecution, and the constant fear for the safety of family members left behind contribute to high levels of stress and mental health issues among Hazara refugees. For those who arrived in host countries via irregular journeys, the uncertainty of asylum processes and the threat of deportation add to this burden.

As explained above, survivor’s guilt is also a common experience among those who were evacuated from Kabul airport in August 2021. The relief of being safe is often accompanied by a deep sense of guilt for those left behind, exacerbated by the dire conditions in Afghanistan under Taliban rule. Many Hazara refugees also face discrimination and racism in host countries, namely, Iran and Pakistan, compounding their sense of isolation and marginalisation.

Another prominent consequence of migration among Hazaras has been the increased political engagement of their diaspora, especially in countries with established communities. Hazara migrants and refugees have become advocates for human rights, both in Afghanistan and in their host countries. For example, we have witnessed different communities of Hazaras in European states reaching out to lobby states and parliamentarians, forming advocacy groups, and raising international awareness about the plight of the Hazara people in Afghanistan. While in the current situation within Afghanistan, Hazaras are almost completely deprived of their political rights, we are expecting that the Hazara diaspora will play a crucial role in shaping political discourse in the future.

And, finally, access to education has been one of the most transformative aspects of migration for the Hazara community. In host countries, Hazara children and young adults have had opportunities that would have been unimaginable in Afghanistan. This access to education has empowered a new generation of Hazara scholars, professionals, and activists who are contributing to their communities and beyond. For many Hazaras, education is seen as the key to breaking the cycle of poverty and discrimination.

These are the histories of individuals and are not representative of the whole Hazara population—not all use smugglers, not everyone returned or wanted to return, the experiences of Hazaras in Iran differed in degree from those in Pakistan, people experienced more or less discrimination, the experience of Afghanistan was not the same for everyone who left Iran, and the journey to the West was also very different for different people.

The following four chapters address different aspects of the Hazara migration experience. Abdullah tells the story of his cousin, a guide who helps Hazaras to leave Afghanistan for Iran and Pakistan, challenging the dominant narratives of smugglers. Smugglers may be criminals, exploiting the desperation and vulnerability of those forced to flee, but those smugglers are a product of increasingly restrictive policies that seek to impose immobility, especially on poor populations. But historically in Afghanistan, Rahbalad (guides) were used to assist those who needed to move to find a place of safety and, as such, treated with respect. This chapter explains the important role people like Abdullah’s cousin play for Hazara migrants.

Atefeh describes growing up as a migrant in the Golshahr area of Mashhad, Iran. For Atefeh and her generation, Golshahr is where the duality of being born and socialised in Iran and being excluded as a muhajir is deeply interwoven with narratives of hope, hopelessness, and struggles for survival and resilience. She describes how Golshahr was both a source of safety and restriction and what it was like as a Hazara woman to venture out into mainstream Iranian society, and the humiliation and rejection she experienced. In this chapter, she refers to the attempts of young Hazaras to resist racialisation, to insist on their right to be more than unskilled labourers.

At different points, Afghans were encouraged to leave Iran and ‘return’ to Afghanistan, especially after the fall of the Taliban in 2001, even though they may have been born or raised in Iran and never left Iran. As Reza explains, those making this journey to a country at once familiar and alien did so with a mixture of hope and trepidation, and this often led to bitter disappointment and disillusionment. While in Iran, we were singled out because of how we look—unlike Pashtuns or Tajiks, we did not blend in and were referred to disparagingly as Afghani. Now in Afghanistan, we were mocked for our Iranian accents, dress, and manners and referred to as ‘Iranigak’, i.e., little Iranians. For many of us, it became clear that to have a future, we needed to move further away.

Although Khadija had done a master’s degree in the UK before she decided to return to ask for asylum, the reaction to her change of status as well as the torture of the asylum process and detention was a profound shock. In Chapter 5, Khadija explains why she made her claim, her asylum journey, and what it was like to find herself in a third exile, where this time hostility and discrimination are tied to the legal status of being an asylum seeker.

The final chapter draws out the lessons to be learnt from these different stories, lessons that can be applied to other groups of displaced people in different contexts, before we suggest some small projects that you might undertake.