DOI: 10.3726/9781916985353.003.0002

The first time I met Saber1 was in our house when I was around 17 or 18 years old, living with my parents in Qom, Iran. Saber was a young man, around 21 or 22 years old, dressed in typical Afghan attire, and just arrived from Afghanistan. He was supposed to stay at our house for a couple of weeks. I remember those two weeks very well; our house became the centre of family gatherings, and people, both relatives and strangers, came and went from early morning until late at night. Saber was at the heart of these gatherings, continuously talking, shaking hands, laughing, and again talking and talking and talking. Despite his youth, everyone spoke to him with respect, even the elderly, addressing him as ‘Saber Khan’! One day, someone knocked on the door. When I opened it, I saw a man and a woman waiting impatiently in the winter cold outside. The man said, ‘We’ve come to see Saber-e Rahbalad (Saber, the Guide).’ It was the first time I heard the word Rahbalad, and I didn’t understand its meaning. So, with an obvious hesitation in my tone, I invited them in. From that day on, Saber’s presence would be felt with friends, relatives, and strangers coming to our house for a couple of weeks every two or three years. As I grew older, I learned that Saber’s job was to bring people from Afghanistan to Iran and take back goods, merchandise, and letters to Afghanistan. However, he was no longer a Rahbalad—people now called him a Qachaqbar (smuggler).

Some years later, during those years, when Afghan refugee youth in Iran were not allowed to attend high school and university, I left Iran for Afghanistan. Tired of the gruelling life with no prospect for the future, I, who had never stepped outside of Qom until then, took a leap of faith and decided to go to Afghanistan, to my father’s homeland, hoping I could create a different future for myself.

First I went to Mashhad and, after staying with one of my cousins for a few days, I introduced myself to the police at the Chahar Cheshmeh camp as an undocumented individual intending to return to Afghanistan. I stayed at the camp for a week until one Saturday, along with about two hundred other Afghans, I was sent to the Islam Qala border. When I crossed the border, I walked with the crowd towards the taxis heading to Herat, but before I reached the station, someone called my name. I turned around and saw Saber smiling and approaching me. He greeted me, hugged me, and simply said, ‘Welcome, Bola Jan (dear cousin)!’ He then explained that the other cousin in Mashhad had informed him in advance that I had introduced myself to the police and would soon be deported to a country I had never seen before. Apparently, he had been coming to the border to find me every day for a week between 2 and 5 PM, the time when the deportees were crossing the border. I found him still cheerful, talkative, and full of life. I was his guest for three days before going to Kabul.

A year after my arrival in Kabul, a family emergency arose in Qom, necessitating my return to Iran. Despite my efforts, I was unable to obtain an Iranian visa through official channels. I contacted Saber and explained my predicament, to which he responded with calm assurance: ‘Don’t worry, Bola Jan. If you come to Herat by this Friday, I’ll take you back to your parents by the next Friday.’ Thus, my journey from Herat to Qom was facilitated by Saber-e Qachaqbar. This journey, along with subsequent meetings with Saber over the years, provided me with insights into his life and profession. These interactions allowed me to engage with other smugglers and understand the broader context of their activities. In 2016, after completing my university education, I joined a research institute focusing on the Afghan displacement experience. Since then, the smuggling of migrants has remained a central area of my focus. In this chapter, I will recount some of the conversations I had with Saber, exploring how he became a smuggler. Additionally, I will present some observations on the dynamics of migrant smuggling within the Afghan context.

Afghanistan has a long tradition of movement and migration, highlighting how Afghan populations have historically utilised migration in various forms (Klaus, 2006). Nomads move to access better pasturelands, businessmen migrate for trade, and pilgrims travel to religious sites, both Shia and Sunni. Migration, in addition, has long served as a survival strategy for Afghans (Monsutti, 2008), particularly during times of crisis. This is especially evident in the country’s recent history, marked by decades of war, political instability, and economic hardship. Over the past 40 years, many Afghans have sought refuge in neighbouring countries like Pakistan and Iran and farther afield in Europe and Australia. The large-scale displacement began with the Soviet invasion in 1979 and continued through the civil wars of the 1990s and the rise of the Taliban. Each phase of conflict and instability has pushed more Afghans to migrate in search of safety and better opportunities. However, challenges in accessing regular migration pathways have persisted. Securing visas is often difficult and costly, involving significant bureaucratic hurdles. These barriers, combined with the pressing need to escape deteriorating conditions, have made Afghanistan a lucrative market for smuggling networks. Smugglers provide services such as transportation, shelter, and assistance in crossing borders. Their role has become so ingrained in the Afghan migration culture that they are often seen as more than just service providers. In many cases, smugglers adopt the persona of saviours, essential figures who facilitate the possibility of finding refuge and a new life in a safe place (Mohammadi et al., 2019).

Smuggling also has deep historical roots in Afghanistan, linked to traditional forms of migration for pilgrimage, trade, and education. Nomads, traders, and pilgrims have long relied on guides or Rahbalads, whose role extended beyond simple navigation; they were responsible for the safety and well-being of those they led. This tradition has carried over into the modern context of migrant smuggling, where individuals like Saber see themselves as continuing a legacy of providing critical assistance in times of need. In fact, the last four decades of political and economic instability have just reinforced the role of smugglers.

Over the last six years, I spoke to many Afghan smugglers in Zaranj, Herat, Kandahar, and Kabul and what I observed is that while the official narrative might associate smuggling with ‘illegality’ and ‘exploitation’, within Afghan society, there is often a more nuanced understanding of this phenomenon. Terms like Rahbalad (guide) carry positive connotations, referring to those who help people in desperate times. Similarly, the term Qachaqbar (smuggler) is used in a relatively neutral manner, devoid of the heavily negative implications it might have elsewhere (Majidi, 2018). This linguistic nuance reflects a broader cultural acceptance of the role smugglers play in Afghan society. Many Afghan smugglers see themselves as providing a necessary service that the government fails to offer. They argue that in the absence of state support and amid widespread corruption, their work is essential for helping people escape dire circumstances. This self-perception is shared by Afghan communities, who view smugglers not as criminals but as practical solutions to a failing system. The story of Saber-e Qachaqbar is a good example.

Following the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan in 1989 and the start of conflicts among various jihadist groups, a civil war erupted throughout the country. Different parties gained control over different zones, mostly along ethnic lines. A similar situation prevailed in some major cities. For instance, in 1992, after the fall of Najibullah’s government, different political groups poured into Kabul, each seizing control of a part of the city. Kabul turned into a segmented city controlled by different political parties organised along ethnic lines: Pashtun, Tajik, Uzbek and Hazara.

One of the first consequences of this territorialization was the movement restrictions imposed by different parties. If someone intended to travel, for example, from Bamiyan to Kabul, a distance of 180km, they had to obtain passage permits from at least three parties. For those who wanted to travel farther and leave the country for any reason, it was very challenging to get all the permits, so Rahbalads provided an essential service. Many Hazara, often travelling in groups, relied on these Rahbalads. They were more than just guides; they were lifelines in a war-torn country where official pathways were blocked or too dangerous.

According to Saber, Rahbalads were primarily individuals involved in trade, accompanying their caravans of pilgrims and travellers to neighbouring countries. Their role extended beyond mere guidance; they were leaders of caravans, responsible for the safety and well-being of the people travelling with them on risky paths.

During this period, Saber and his family were living in Bamiyan. His father was originally a trader and one of the local Rahbalads, someone who from an early age travelled frequently to Kabul, bringing goods and food supplies to Bamiyan. Alongside domestic travels, he also travelled to Pakistan and Iran for trade and had a shop in Quetta.

My father usually travelled every year between Bamiyan, Kabul, and Quetta, and sometimes twice a year. He had a car and would take local products, such as butter, qurut (dried cheese), rugs, and skins from Bamiyan to Kabul. He also transported patients to Kabul for medical treatment. After Kabul, he would load up with other goods and head across the border with Pakistan towards Quetta.

Alongside his business, Saber’s father was involved in political activities and had connections with Hizb-e Wahdat, the Hazara political group that controlled Bamiyan and the west of Kabul at that time. Almost all political parties and factions had offices not only in Afghanistan but in Pakistan and Iran as well. These offices served as representatives for Afghan migrants in those countries and as political liaisons with host country authorities. However, due to the lack of communication networks at that time, communication between these offices was not straightforward, and messages and letters were carried and circulated by individuals. These letters were not given to just anyone. Due to potential risks and sensitive information, only trusted individuals could carry these messages.

Saber’s father was one of those trusted individuals. Saber remembers how his father used to deliver letters on some of his journeys to Quetta. His father even took him along sometimes since the presence of a child made them less suspicious:

He sometimes took me with him on these journeys, and I would see that in Kabul, before heading to Quetta, he spent 2–3 days visiting relatives and acquaintances, and some other individuals. During these visits, some letters with addresses were given to my father, which he took with him to Quetta and delivered to their acquaintances. Later, I found out that some of those letters were political letters that my father brought from Bamiyan and Kabul to Quetta.

The return journeys were similar, with many letters entrusted to his father, not only political letters but also letters from relatives, friends, and strangers who wanted to send messages to their loved ones in Afghanistan. This letter delivery was almost a regular and routine practice since at that time there were no phones or computers that allowed everyone to contact their family and loved ones within minutes.

Accompanying his father on journeys gradually acquainted Saber with the intricacies of trade and travel. He learned that products like dairy products, edible oil, and rugs from Bamiyan had many customers in Kabul. Additionally, items like skins, carpets, and dried fruits from Kabul sold well in Quetta. Bringing home appliances, batteries, textiles, as well as certain food supplies from Quetta to Kabul and Bamiyan proved to be lucrative for them. Saber also became well-acquainted with the routes; he learned where to stop at nights, where they expected to face a checkpoint, what to say at various checkpoints, to whom they should give bribes or what permits to show at each checkpoint, and how to conceal letters:

When we had sensitive letters, it wasn’t just writing them on paper and maybe hiding them in a pocket or inside the vehicle. If someone at a checkpoint became suspicious and wanted to interrogate us, then they would turn the entire vehicle upside down and search all our pockets. So one thing that my father sometimes did was to write very sensitive letters on a piece of cloth, tying it around my waist. Once they even wrote a letter on the undershirt I was wearing. I was a teenager, and rarely did someone touch a teenager like me, especially in the presence of my father.

During these journeys, Saber noticed the respect people had for his father. This respect wasn’t just due to his relative prosperity but also because of his role in connecting separated families and people—acting as a bridge between two worlds. He was a kind of messenger:

Everyone loved my father. Whenever we were in Kabul or Quetta, mornings, afternoons, and evenings were filled with invitations. My father was highly esteemed. People knew that he was risking his life for them.

Gradually, Saber realised that he, too, had a share in this respect, and people looked at him differently. No one treated him like an ordinary teenager, and they addressed him as ‘Agha Saber (Mr. Saber).’ However, these journeys were not easy for a teenager. Witnessing his father being insulted by authorities, and in some instances, being beaten, left a bitter memory for Saber. However, just as Saber witnessed the growth of his father’s business, he also observed the development of his own skills in managing challenges and risks along the journey. When I asked him what skills he is talking about, he mentioned learning Pashto language as an example, a skill that proved to be beneficial in many places en route:

Learning Pashto in our profession is vital because, ultimately, we have to pass through Pashtun territories. If we speak with them in their own language, they treat us much better, and if the person is not hostile, even a sense of friendship may develop between you.

When I asked Saber about the first time he independently undertook a journey, he referred to his first trip without his father’s presence. It was a time when his father had gone to Quetta earlier, and a sensitive political issue happened in Kabul that necessitated sending an urgent letter to Hizb-e Wahdat’s office in Quetta. Since no one else was available, one of the Hizb’s officials asked him to accept this responsibility. Under the guise of a family trip, he, accompanied by two men, two women, and five children, accepted the responsibility of delivering the letter to Quetta. He performed this task and repeated such journeys to Quetta and later to Iran several times.

Travelling during that period was not like today. Since border control and passport systems were not as strict, convoys of vehicles could cross the long borders between Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran. Additionally, the open-door policies of both countries regarding Afghan refugees meant that these journeys, although lengthy, exhausting, and perilous, could yield results. Therefore, the term ‘illegal’ as used today did not have the same connotation for people regarding these movements. According to Saber, ‘at that time, the land was God’s land, and no one asked whether you had a passport or not. At the Pakistan border, when officials asked where you came from, we said Afghanistan, and they just recorded our names, took some money and had no further concerns.’ If there were checkpoints and guards asked for bribes, it was the task of a Rahbalad to handle this and manage the entire arrangements from the start to the end of journey.

The years 1998 and 1999 were difficult times for Saber and his father. The Taliban had almost taken control of the whole country, persecuting religious and ethnic groups including Hazaras. Another phase of mass displacement began from Hazarajat. Hazaras were faced with discrimination, threats, and extrajudicial killings throughout the country. In this context, the elders in Yakawlang district in Bamiyan, where Saber was living, formed a Shura (local council) to discuss their options. In this council, a decision was made to send the young men and teenage boys to Iran as they were most exposed to danger should they remain in Afghanistan. Saber recalls from the council that after much discussion about the future and possibilities, ‘almost everyone agreed that dark days awaited the people, and the best course of action was to send the youth and family members to Iran or Pakistan’.

After the decision was made, the discussion turned to how to send them. The debate began about which route to take and with whose assistance. Two elders requested his father’s opinion and asked him to accept this responsibility to act as a guide, leading the people to safety. His father accepted, and it was decided that he would make a journey to Herat to coordinate the journey arrangements with his fellow Rahbalad there, and two months later, they would set out. However, on the way back from Herat to Bamiyan, he was arrested and detained by the Taliban militia. Faced with this unforeseen problem, the council sought a new solution and, after much deliberation, realised they had no option but to turn to Saber to assume his father’s role. Saber explains:

I had to assume the responsibility and take our villagers to Iran. My father had already done all the coordination; all I had to do was to take the people to Herat and from there to the border with the help of my father’s colleagues.

The decision to migrate, especially under such perilous conditions, was not taken lightly by the community. It involved extensive discussions and consensus-building within the Shura, reflecting a deeply ingrained practice among the Hazaras. The Shura played a critical role in decision-making on social matters during crisis periods. This collective approach ensured that decisions were made in the best interest of the community, considering all potential risks and benefits. This sense of duty among Hazara community leaders was extended to ensuring that those who migrate are in the hands of trusted and capable Rahbalads who are not just guides but also protectors and leaders.

Taking on the responsibility that his father had left behind was not an easy task for Saber. The journey from Bamiyan to Herat and then across the border into Iran required meticulous planning and coordination. The first step was gathering the group of villagers who had decided to make the perilous journey. This involved meetings and careful discussions with each family to ensure that everyone understood the risks and responsibilities involved. The journey from Bamiyan to Herat took three days. He had to arrange one pickup and a minibus to take the group to Herat. To minimise the risks, they put the boys among the families in the minibus to make sure they were not very visible. Saber also had to pay bribes at every checkpoint along the route. After reaching the limits of vehicular access, the group continued the rest of their journey on foot, traversing mountains and villages. However, what most proved invaluable was his ability to negotiate with local elders and checkpoints guards in Pashto:

I tried to be friendly as much as possible and speak to them in Pashto. Pashtuns and Talibs are very proud of their language, and when someone speaks to them in their language, they become very happy… To avoid trouble and conflict, you should try to show yourself as a friend of the Pashtun people. Besides that, for instance, if you address any of the soldiers as ‘Mullah Sahib’ they will be pleased and it will at least prevent them from starting a conflict with you from the beginning.

Upon reaching Herat, Saber met with his father’s colleague, who was an experienced Rahbalad himself. He provided crucial support and advice, helping Saber to reconsider the route and ensure the safety of the group. They discussed the best routes to take, the checkpoints to avoid, and the bribes that might be necessary to smooth their passage. The network of Rahbalad was extensive and helped Saber to build strong relationships with many people along the route.

The next phase of the journey involved crossing into Iran via Pakistan, a task that required the assistance of two other Rahbalads at the border, one Hazara and one Baluch. The detour was critical due to the high presence of Taliban patrols along the Afghanistan-Iran border and the fear of militia groups and criminal gangs which made a direct crossing too dangerous. The Hazara Rahbalad, who was well-known in the community for his reliability and connections, helped to arrange safe passage through the most dangerous parts of the route. He coordinated with the Baloch Rahbalad, who had extensive knowledge of the border areas and could navigate the group through the difficult terrain. The Baloch Rahbalad’s role was particularly crucial when it came to crossing the actual border to Pakistan and from there to Iran. He guided them through the barren deserts and rugged mountains, often using little-known paths to avoid detection by militia. The journey was exhausting, and the group had to move quickly, with little rest, to minimise the risk of being caught. They had to ensure that everyone stayed together, especially the children and elderly, who were more vulnerable:

If someone got lost on those routes then their fate was in God’s hand as we didn’t have the time to stop and search for the lost otherwise more people’s lives would be at risk.

Upon crossing into Iran, the group still had a long way to go to reach Tehran.

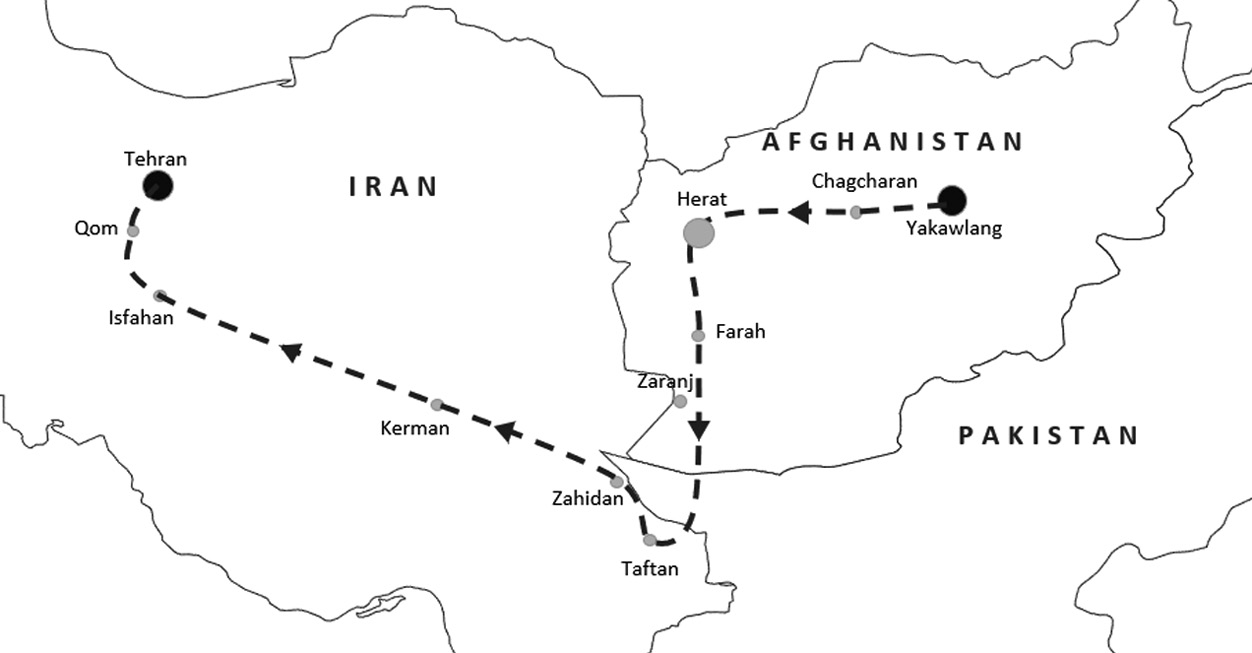

The route that Saber took to take the group to Iran

They had to navigate through different cities, avoiding border patrols and police. Saber and the Hazara Rahbalad took charge during this phase, using their connections to find safe houses and arrange transport. The journey from the border to Taftan through Pakistan territory and farther to Zahidan was all on foot, a test of endurance and willpower. The group faced hunger, thirst, and the constant threat of capture:

Our journey was in the summer, so the weather was very hot, especially in Taftan and Zahedan. Many people suffered from heatstroke. There was a shortage of water. The wells along the way had water, but drinking it made us sick. Almost all the children got diarrhoea and became ill.

However, after ten days and frequent stops along the way, they reached Qom and then Tehran:

We delivered most of the group to their families and relatives in Isfahan, Qom, Tehran, and later in Mashhad. When we reached, for example, Qom, we would go to one of the relatives’ houses, and everyone would get off there. Then we would inform people from our village in that city that the group had arrived in Qom and was at a certain person’s house. After that, people would come to see if their parents, siblings, or close relatives were in the group or not. If they were, they would take them to their own homes... Each time someone was taken, it felt like a burden was lifted off my shoulders.

Saber’s successful navigation of this journey and his ability to safely lead his group to Iran earned him significant respect and recognition within the community. This was no small feat, as becoming a recognized Rahbalad required not only skill and bravery but also a strong network and an impeccable reputation. Trust was paramount, and Saber had proven himself to be trustworthy.

The ethnic network played a crucial role in this recognition. These networks extended across borders, connecting communities in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran. The interconnectedness provided a support system for those on the move, offering places of refuge, assistance, and information along the way. Saber leveraged these networks to facilitate the journey. In each major stop along the route, there were trusted individuals and families who provided shelter and support. These connections were not just practical but also emotional, offering a sense of continuity and community even in the most challenging circumstances. The strong ties within this network also meant that news of Saber’s successful journey spread quickly. Word-of-mouth recommendations were powerful, and soon more people sought Saber’s assistance for their journeys. His reputation as a reliable and honourable Rahbalad grew, further embedding him within the network of trusted guides.

In addition to the support from ethnic networks, Saber also benefited from his father’s reputation. Among the Hazaras, relationships and reputations were built over generations, and Saber’s family had a long history of serving the community. His father’s legacy as a respected Rahbalad provided a strong foundation for Saber to build upon, and his successful journey further solidified his standing. Of course, his own qualities contributed to his recognition too. His ability to speak Pashto, his knowledge of the routes, and his skill in negotiating with various actors along the routes were all critical. His calm demeanour and decisive actions under pressure, which I personally witnessed on my journey with him, reassured those he guided, fostering a deep sense of trust.

After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, Saber moved to Herat and settled there with his family. His father opened a small grocery shop and, beside that, started to work as a Hawaladar as a side job. In a country where formal banking systems were either unreliable or inaccessible to most, Hawala networks provided a crucial service, enabling the transfer of money over long distances and across borders. Saber’s father’s connections and trust within these networks were invaluable, establishing a foundation for their economic activities.

Saber, alongside helping his father, ventured into the food business by opening a small restaurant in a Hazara neighbourhood in Herat. His customers were predominantly Afghans travelling to and from the Iranian border. Many were returnees or those seeking a better life in Iran. The difficulty and expense of obtaining visas made regular migration channels prohibitive, pushing many towards irregular means. Saber, busy with restaurant work, put his work as a Rahbalad aside and travelled only once a year to visit relatives and friends. He remembers that ‘people were coming to me to cross the border, but the [restaurant] business was good and I didn’t have any time, so I referred them to others.’

The years 2005–2006 marked a significant change in the dynamics of border crossings between Afghanistan and Iran. Increased border security and the construction of walls on parts of the Iranian side of the border made traditional routes more perilous and less feasible for smugglers. Consequently, the smuggling networks shifted their operations towards the southwest, using Pakistan as a transit route. Zaranj, the capital of Nimruz province, emerged as a crucial hub for these networks due to its strategic location and the porous nature of its border.

By 2010, Saber faced increasing difficulties in Herat. Corruption was rampant, and local authorities, along with criminal gangs, frequently extorted money from business owners. The extortion became so burdensome that Saber found himself with little to no profit after paying off these demands:

Life had become very tough in Herat... Not only me but any trader or anyone whose situation seemed a bit better was targeted by them… In the last few years, I paid them so much in bribes and extortion monthly that there was nothing left for myself at the end of the month. For people like me who had nobody to back them, there was no future in Herat.

He decided to move to Zaranj, a city he knew well and where he had established connections. A friend suggested a partnership in purchasing a hotel, seeing the potential for profit in catering to the needs of migrants and smugglers. Saber consulted with his father and agreed to the venture. They bought a hotel, which quickly became a bustling centre of activity, serving as a resting place and a meeting point for migrants and smugglers alike.

Describing Zaranj, Saber painted a vivid picture of a city thriving on smuggling, ‘a city that has covered its face in dust like an unfortunate construction worker. But beneath this dust, it’s all money and wealth,’ he said. The city’s economy is intricately linked to the smuggling of a variety of goods—motorbikes, fuel, drugs, household items, carpets, and medicine. However, migrant smuggling was among the most profitable trade, with Zaranj serving as the gateway for Afghans seeking to enter Iran irregularly. According to Saber, the city’s survival depended on smuggling: ‘everyone from any class or any business somehow passes their days with smuggling.’ When I visited Zaranj in 2018, I understood what Saber meant. The local economy is intertwined with this illicit trade—drivers transport migrants, shopkeepers sell goods to them, hotel owners rent rooms, and restaurants provide food. Even the police and government officials are complicit, taking bribes from smugglers and migrants. As Saber explained: ‘If they remove smuggling from Zaranj, nothing will be left but ruins and an empty plain.’

When I asked him about the legality of smuggling and people’s perceptions of smugglers in Zaranj, Saber laughed and said:

This is Afghanistan, which law? The law of the Afghan government that is corrupt from top to bottom? Or the law of the Iranian government that only knows oppression against Afghans?

He questioned the legitimacy of a government that failed to provide security or work for its people, arguing that such a government had no right to impose laws or define rights and duties. As he put it:

People determine what is right and what is wrong. They say Haji Rahman [Saber’s father] is a good person and Karzai is a corrupted one and the government says Karzai is good, Haji Rahman is bad. On the Judgment Day, who do you think God will prefer: Karzai or my father?

Saber’s rhetorical question underscored the deep mistrust in formal state institutions and the alternative moral system that had emerged in their place. When I asked if he considered himself a Qachaqbar, Saber’s response was both practical and philosophical: ‘Well, some people call me Rahbalad, some call me a merchant, and others call me a Qachaqbar. Whatever name they call me, they still need me.’

Saber’s role was far from easy. Managing a hotel in Zaranj is a complex and risky endeavour, involving constant interaction with migrants, smugglers, police, government officials, and other players. ‘You just see the hotel, but it’s a city in total chaos,’ he said, highlighting the daily challenges and responsibilities he faced. He believes that trust and a good name is the key for a successful business in Zaranj and this trust was not lightly given:

If I were a bad person, they wouldn’t trust me to take their namoos [wives and daughters] and children through mountains and deserts. See, they trust me as someone who stands by his word and doesn’t betray their honour. This is not a small talk. If the government says our job is illegal, who cares about the government? Who listens to this government?

Despite the challenges, Saber continues his work. The last time I spoke with him was in May 2024 via a WhatsApp call. I asked him how he was doing, and he said that his hotel was busy, and the number of Afghans travelling through Zaranj had increased since the return of the Taliban to power. When I asked him about the changes in the last three years, he replied with his usual humour: ‘Khar haman khar ast, faghat palanesh avaz shodeh’ (the ass is the same old one, just its saddle has changed). He was trying to convey that it doesn’t matter who is in power, whether it is Ashraf Ghani or the Taliban, the miseries and hardships of Afghanistan remain. As long as these difficulties persist, Afghans will be forced to migrate. My final question to him during our WhatsApp call was whether he had any plans to migrate himself. He responded:

Migration requires courage and youth. I’m past that stage. I’m getting old and there is nothing for me in Ghorbat (exile). I’ve built a lifetime of reputation and respect here. Why would I go where no one knows me and I am no one?

I believe this statement encapsulates the depth of his connection as a Qachaqbar to his people and the complex realities of Afghan migration. It also reflects a broader theme in the Afghan migration: the struggle to maintain dignity and survive in the face of hardship and adversity, highlighting the deeply embedded realities of smuggling in Afghanistan, where personal and communal identities are intricately tied to the land and its enduring challenges.

Through conversations with Saber and other Afghan smugglers, it became clear that the realities of Afghan migration are far more complex than official narratives typically convey. Afghan smuggling networks operate within a web of social, economic, and cultural factors that both drives and sustains them, revealing a picture that diverges from stereotypical portrayals of smugglers as mere exploiters of vulnerable populations. Instead, they are often seen as essential actors within their communities, providing services that, in the absence of state support, are necessary for survival and dignity. While rooted in the Afghan context, these insights resonate with migration dynamics in other regions facing similar challenges (Majidi, 2018). For ethnic communities like the Hazaras, smuggling networks have become embedded within their social and economic structures that offer resilience in the face of external pressures. Smugglers like Saber are not isolated criminals but integral members of their communities who uphold values and provide a measure of stability where the state structures fall short. This section offers a closer look at some of these insights, reflecting on broader implications for understanding irregular migration from Afghanistan.

In Afghanistan, smuggling operates within a unique cultural framework where figures like smugglers have been often regarded as guides rather than criminals. Unlike the stereotypical image of a smuggler as a predatory actor exploiting the vulnerable, Afghan smugglers—especially among marginalised groups like the Hazaras—are seen as community figures who provide essential support in times of need. Historically, Rahbalads were responsible for guiding and protecting traders, pilgrims, and families through difficult terrain, offering not only navigation but also protection from external threats. While the modus operandi of these networks has evolved over the past two decades—such as the shift from the term Rahbalad (guide) to Qachaqbar (smuggler)—their role in the eyes of the community remains largely unchanged, as they continue to be perceived as guides who offer pathways to safety and opportunity in a landscape rife with danger and instability.

Saber’s journey reflects this deeply rooted perception. Despite the hardships of his work, people continue to turn to him for help, trusting him to transport their families across borders. In his community, Saber embodies qualities that Afghan society holds in high regard: loyalty, resourcefulness, and a sense of moral duty to those he assists. This perception stands in stark contrast to international and state narratives, where smugglers are portrayed as grasping opportunists. For Afghan communities, however, Saber and others like him are regarded as more than mere facilitators—they are seen as figures who through their work uphold important values of honour and trust, despite the personal risks involved.

This alternative cultural framework challenges the dominant narrative that smuggling is solely an act of exploitation. In the Afghan context, smugglers are not just facilitators of migration but custodians of cultural and communal values, helping to maintain family unity, dignity, and survival. Within the Hazara community, smugglers have also played a crucial role in preserving kinship ties across borders. For families who face persecution and limited access to formal migration pathways, smugglers have been not merely service providers but are respected as key figures upholding the community’s dignity and resilience. By connecting people with kin, protecting the vulnerable, and navigating uncertain terrain, smugglers like Saber are embedded in a cultural tradition that values survival, honour, and mutual support.

The economic impact of smuggling in certain Afghan regions, particularly border towns like Zaranj, is profound. In these areas, the local economy depends heavily on the steady flow of migrants and the associated demand for goods and services. In Zaranj, for instance, smuggling is a critical driver of local livelihoods, providing income for many individuals, from drivers and shopkeepers to hotel owners and food vendors. Smuggling sustains the community and has become woven into the region’s economic fabric, allowing families to earn a living in ways they might otherwise be unable to achieve in a region with limited formal employment opportunities.

During my time in Zaranj, it became evident how deeply smuggling influences everyday life. The city’s economy is shaped by a demand for services that cater to migrants: transportation, lodging, food, and even informal money transfer services are all tailored to facilitate the migration process. For people like Saber, running a hotel and connecting migrants with trusted routes offers a steady income that not only supports his family but also sustains the local economy. Businesses in Zaranj rely on the smuggling trade to such an extent that any disruption to this activity would likely destabilise the community and create significant hardship for those who depend on this economy.

Furthermore, international anti-smuggling policies, which seek to curb migration flows, rarely take into account these economic dependencies (MMC, 2021). Measures that target smuggling without addressing the economic realities risk causing more harm than good, leading to deeper poverty and insecurity. With few alternative economic prospects, local populations may be driven to adopt even riskier survival strategies, intensifying the need for migration rather than curbing it. This dependency has a ripple effect on the community, where smuggling acts as an economic stabiliser, ensuring that local residents can access income in a region largely overlooked by state economic planning. For Saber and his community, smuggling is not a criminal enterprise; it is an economic lifeline that sustains entire families, if not neighbourhoods, and provides stability amid an unpredictable economic landscape.

The contrast between community and state narratives on smuggling reveals fundamental differences in how legitimacy and morality are defined. Official narratives frequently depict smuggling as an inherently criminal act associated with exploitation, framing smugglers as individuals who prey on vulnerable migrants, stripping them of agency and security. However, within Afghan communities, particularly among those who directly benefit from smugglers’ services, these figures are viewed in a far more positive light. Smugglers like Saber are seen as honourable and trustworthy individuals who fulfil a role that governments fail to provide, enabling safe passage, family reunification, and access to opportunities that would otherwise be out of reach.

In Afghan society, legitimacy is rooted less in state-imposed laws and more in the values of trust and reliability within the community. This is especially true in rural and marginalised communities where the state is perceived as an external force. Saber’s story exemplifies this divergence in perception: while authorities might label his work as illegal, his community sees him as a necessary actor providing a vital service for survival. His community’s trust is based not on his adherence to the law but on his reputation as a Rahbalad rather than a Qachaqbar —a guide who upholds promises, ensures safety, and facilitates paths to better futures. This community-based legitimacy not only challenges the state’s criminalization of smuggling but also reflects broader tensions between community autonomy and state authority (Nimkar and Mohammadi, 2023). For Afghan communities, as long as the state fails to offer viable migration pathways, smuggling will continue to be seen as a morally acceptable, even essential, survival mechanism that aligns with communal values and shared goals.

Corruption within Afghan state institutions significantly affects both the operations of smugglers and community perceptions of their legitimacy. Along Afghan migration routes, bribery is rampant, with smugglers frequently paying off officials to secure safe passage. This systemic corruption not only allows smuggling operations to thrive but also erodes public trust in the government. For smugglers like Saber, repeated demands for bribes at every checkpoint reinforce the view that the state acts less as a protective authority for Afghan citizens and more as a barrier that must be bypassed. Consequently, smugglers see themselves as essential service providers stepping into roles that the state should, ideally, fulfil. This environment of corruption serves as both a challenge and a justification for smugglers. The constant bribery demands create an added ‘cost of doing business,’ which Saber and others pay in exchange for performing critical roles that protect vulnerable people. This perspective distances smugglers from state-defined criminality, framing their work not as exploitative but as a necessary response to the state’s failure to offer safe migration paths. To smugglers, the corruption they navigate legitimises their role, as they continue providing services that are otherwise unavailable through formal channels.

Corruption also shapes public perceptions of smuggling, reinforcing the community’s view of smugglers as legitimate actors in a system plagued by state complicity and inefficiency. When communities witness police and officials accepting bribes, they perceive the state as ineffective and untrustworthy. For many, the state’s inability to enforce fair practices or provide secure migration pathways severely undermines its authority, leaving communities with few choices but to rely on smugglers. This strengthens the view of smugglers as alternative providers of essential services, such as safe passage, guidance, and economic opportunity. Saber’s rhetorical question about which authority—the state or the community—has the moral high ground echoes this sentiment. To him, as to many others, smugglers who honour their promises and uphold community values hold a legitimacy greater than that of a state compromised by corruption.

In Afghanistan, the perceived legitimacy of smuggling is largely shaped by moral frameworks deeply rooted in community values, kinship, and trust. While formal State perspectives often reduce smuggling to a legal issue, Afghan communities assess it based on its outcomes. If a smuggler like Saber successfully helps someone escape persecution, reunites a family, or provides a means of economic survival, his actions are viewed as morally justified, regardless of their legal standing. This moral legitimacy is intertwined with the concepts of trust and honour—values that are central to Afghan society and earned through consistent, reliable service. Trust is especially important in these networks, as smugglers who fulfil their promises and protect their clients’ well-being build a reputation that becomes their most valuable asset (see: Nimkar and Mohammadi, 2023).

Saber’s story illustrates how such trust is developed over years of service, through strong connections and a reputation for safeguarding clients’ dignity. His ability to communicate in Pashto and navigate different cultural and political landscapes enhances his credibility, fostering relationships across ethnic divides that might otherwise be inaccessible. In Afghan communities, trust in a smuggler is often stronger than trust in the state, particularly among the Hazaras, where longstanding ethnic networks support migration both as a survival strategy and as a means to preserve dignity in the face of state neglect. For many, smugglers like Saber become respected figures who uphold the community’s honour and protect values that formal systems fail to safeguard. This socially embedded trust framework, which holds smugglers to high standards of conduct, positions smuggling as a morally legitimate endeavour, embedded within Afghan society’s resilience and adaptability.

Contrary to assumptions that smugglers play a primary role in encouraging migration, Afghan smugglers more often serve as facilitators of already-made decisions. For families in crisis, the choice to migrate is not taken lightly and often follows lengthy discussions involving family members and community elders. For those facing persecution, economic hardship, or the desire to reunite with family members abroad, migration is a strategy for survival—sometimes a forced response to immediate threats and other times a spontaneous decision when unexpected opportunities arise. In this context, smugglers act as facilitators who provide the knowledge, resources, and logistical support necessary for a safe journey.

Once the decision to migrate has been made, reliance on smugglers like Saber becomes indispensable. Saber’s extensive experience and knowledge of routes, border procedures, and local customs make him a valuable ally for migrants navigating perilous journeys. This dependency reflects the lack of formal support systems in Afghanistan, where the state’s absence pushes migrants toward informal networks. The necessity of relying on smugglers for safety, food, and shelter makes their role critical in the migration journey, as smugglers offer both guidance and a degree of security.

Saber’s role demonstrates that smugglers often do more than provide a route; they become temporary protectors, guiding families through unfamiliar terrain and offering assurance. The dependency on smugglers is therefore not solely a matter of logistics but a deliberate choice, rooted in the recognition of their role as guardians of survival in an unpredictable environment. For many Afghan migrants, smugglers represent not a vulnerability but a partnership—a way to navigate complex, high-risk journeys with a level of dignity and security that they would not otherwise possess.