by Cindy Horst

We are all confronted on a daily basis with ongoing wars and occupations as well as increasing polarization and inequality. Rather than strengthening the power of art and dialogue, decisionmakers turn to securitization and militarization – strengthening fear, hatred and despair instead of trust, solidarity and hope. This approach runs the real risk of creating increasingly extreme positions on the one hand, or apathy on the other. In today’s world, a 15-year-old quote from historian, political scientist and playwright Howard Zinn remains highly relevant:

“To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness. What we choose to emphasize in this complex history will determine our lives. If we see only the worst, it destroys our capacity to do something. If we remember those times and places— and there are so many— where people have behaved magnificently, this gives us energy to act, and at least the possibility of sending this spinning top of a world in a different direction. And if we do act, in however small a way, we don’t have to wait for some grand utopian future” (Zinn 2009: 14).

If there is anything my almost three decades of life history-based research with people with lived experience of war and oppression has taught me, it is that war, oppression and exile can trigger civic and political participation. Those who have experienced the worst in mankind can develop a political awareness and a strong sense of responsibility to act in the face of injustice. As ‘Forough’, a social activist of Iranian descent in Norway explains her motivation to engage: ‘We take part because we have to. After all, I am very privileged […] When I get how things connect together then I just can’t not do something’.

While many people around the world can relate to the sense of responsibility that Forough expresses here, in recent years there seems to be an increasing understanding of urgency matched with a feeling of despair in light of the ‘dark times’ we hear and see about – or experience ourselves. So how do we remain hopeful to maintain ‘the energy to act’, in however small a way?

Creative Resistance tells the story of Monirah, Halleh and Diala – three extraordinary women who found a path to hope through action in the face of violence. Monirah Hashemi is an actor, playwright and director who worked with theatre and film to address a range of social justice issues in Afghanistan and now in exile in Sweden. When she talks about her artistic practice, she explains how theatre and film were never going to be for entertainment. ‘For me, it would be the most important tool. For me, art would be the torch, a kind of guiding torch, a light that I can take to make the path clear for myself. But in that way, of going that direction, many other women can also use that torch’.

Halleh Ghorashi is a professor at the Free University Amsterdam. As a teenager she took part in the 1978-79 Iranian Revolution and ten years later she had to flee and arrived in the Netherlands. She compares the othering she has experienced in Iran with the stereotypes she faces on a daily basis in the Netherlands. Such stereotypes are based on images we have of each other that become so normalized in our daily life that we don’t think to question them. Halleh is actively engaged in working against this reality, and says ‘The only way to go about it is to invest in interpersonal relationships and make them more thoughtful. Those thoughtful relationships create waves of influence, can travel all around the world and inspire others to do the same thing’.

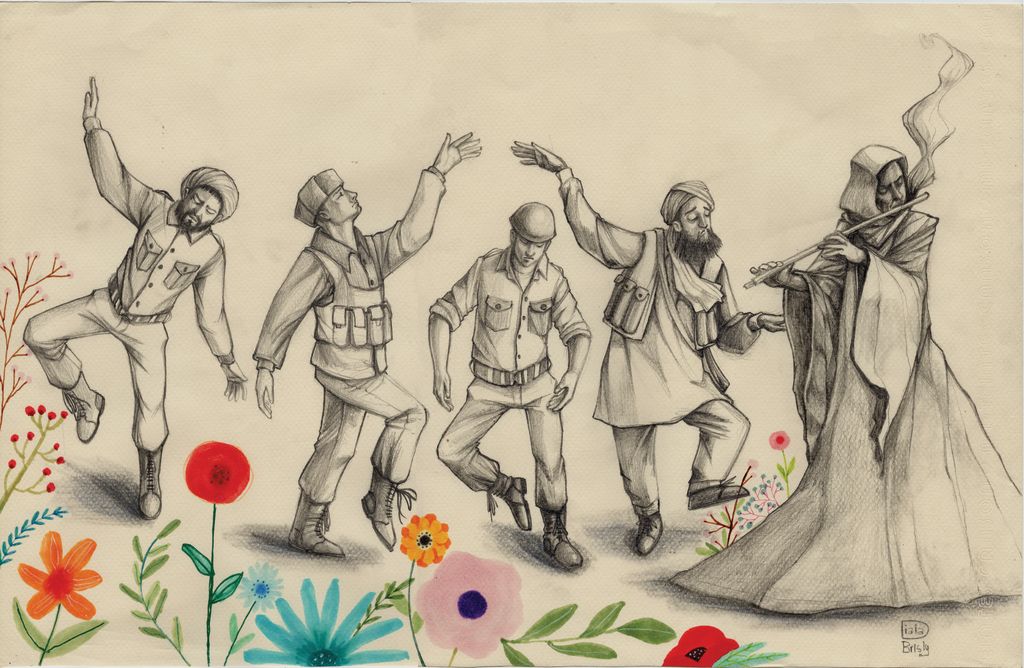

Diala Brisly is a Syrian artist living in France whose artistic practice spans a variety of media, including animation, painting, comic books, illustration and murals. She was active in the Syrian revolution, and like Halleh had to leave her country in order to survive and be able to continue her social justice work. Part of her artistic practice focuses on working with children affected by war. Reflecting on the impact of her work, Diala says: ‘I know maybe it’s a drop in the ocean, but it’s better than nothing. […] We had way bigger dreams than we could achieve, and when you feel like you can’t really achieve what you are doing, you feel depressed. So I decided to make my goals smaller so I can at least be rational and achieve them. So now I think, even if we can work with a few kids and change a few kids’ lives, it’s better than nothing’.

Many of us are inspired to act in solidarity with those in other places who face violence and oppression and/or recognize the need to act in our own neighbourhoods and society. We might feel a sense of urgency and despair, of isolation and alienation. This makes it all the more important to recognize ‘the many times and places where people have behaved magnificently’, and to be inspired by and build strategic networks with those people.

As Halleh puts it in a TedX talk: ‘We do not start with a revolution when the power is so subtle and invisible. We start investing in each other and giving the relationship and the conversations we have more color and multiplicity. And maybe […] then we can have some kind of revolution by just deconstructing the blind spots in our own thoughts’. Monirah, Halleh and Diala all in their own ways stress the importance of building community. Diala argues: ‘We can’t really let these people control everything. We have to resist. At least we can resist, you know’ […] I want to be a drop in the ocean with other drops in the ocean. Because there are a lot of people still trying. I am not alone’.

Individuals exist in and through relationships with others. We need to shift from an individual to a relational ethics – learning from those communities that live in recognition of our shared fate on earth. If we manage to make this shift, it will no longer be surprising that people show response-ability to those in distress, since ‘their own existence as subjects depends on the dignity of all and the continuance of the social order. What becomes surprising and in need of explanation instead is why sometimes people see others’ suffering as none of their business’ (Edkinds 2003: 256).

How can hope flourish from the devastation of war, oppression, and forced migration?

For the people featured in this book, this is not a philosophical question – it is a lived reality. Drawn from first-hand experience of violent conflict and displacement, the stories in this book belong to three extraordinary individuals who found a path to hope through action in the face of violence.

Ideal reading for academics, artists, and activists who are working around issues of social justice, Creative Resistance highlights the extraordinary actions of ordinary people in dark times.

We want our books to be available to as many people as possible. If you’d like to purchase an individual copy, please email us and we’ll give you a discount code:

HEADER IMAGE CREDIT: Pied Piper, Diala Brisly. Used with permission.