DOI: 10.3726/9781916704459.003.0001

This book describes the juvenile justice system in South Carolina from the perspectives of those involved. Information in this book will be helpful to those studying the criminal justice system and adolescents. Stories in the book are compilations of individual experiences and do not reflect a particular person, rather they are the combination of multiple participants. Stories have been created through interviews with judges, sheriffs, probation and parole officers, lawyers, advocates, the formerly incarcerated, and written documents from incarcerated youth. The book is laid out in five chapters:

1. Entering the juvenile system

2. Incarceration in South Carolina: The system

3. Supporting incarcerated juveniles

4. Life inside

5. Recommendations for change

Each chapter follows this format:

Guiding question(s), Learning outcomes, Content, Summary, Discussion questions, Extension activities, Resources

Chapter 1 provides an overview of the juvenile justice system in South Carolina. Chapters 2 through 4 present more personal and individual stories based on interviews, observations, and research of the South Carolina juvenile justice system. Chapter 5 contains recommendations based on interviews, observations, and best practices.

Kimberly Nolan is a teaching professor in the Graduate School of Education, Northeastern University, specifically, the Doctor of Education program. She has been a full-time faculty member since 2013. Her research interests include school climate, experiential learning, action research, and student-centered schools. Dr Nolan is a leader within Northeastern’s Network of Experiential Learning Educators (NExT) in the Graduate School of Education and throughout the university. She is the lead faculty for Northeastern’s EdD program in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Dr Nolan has more than 20 years of experience in K-12 education, including experience as a middle school science teacher, K-12 assistant principal, and alternative high school principal. In addition, she has worked in the community college system as a faculty member and administrator.

As a young educator, I worked most passionately with “those” kids. “Those” kids are the ones lingering in the hallway after the bell, smoking on the corner before school, slumped in a chair in front of the principal’s office, staying out too late … the troublemakers. From my very first days running the after-school center in a Boston housing project, I strove to know the kids I worked with, even though I had very little in common with them. As a college senior, I drove into poorer parts of Boston from a wealthy, safe suburb to supervise 12- to 16-year-olds in after-school centers located in basements and long-forgotten lobbies of large, run-down housing buildings. I remember leaving the building in the dark hoping that my car was still there in the parking lot. When the kids got to know me, they would walk me to my car because, in the words of my charges, “Anybody can tell you don’t belong here.” I found this work rewarding and heartbreaking. Long-time students would disappear, and later I would learn they had been moved into a group home, arrested, shot, or experienced countless other traumatic events.

I moved on to become a middle school science teacher in the Bronx, in New York City. I had enough general science and math credits to get an emergency teaching license despite my total lack of training in education. Thus, I began my career as a teacher. To say the first year was difficult would be a complete understatement. But, by year two, I loved my job, and my assistant principal noted that I had good classroom management because I developed genuine relationships with my students. Difficult kids were frequently moved to my class after getting in trouble elsewhere. After four years of teaching, I had a master’s degree in education and a true license. I wanted more; I wanted to be an administrator. I went on to obtain a master’s in educational leadership and secured a job as dean of students at a middle school in rural New England. While working as an administrator, I earned my doctorate in education leadership and policy. I became an assistant principal at the middle school and later a principal at an alternative high school.

All the while, children with behavior issues became “my” kids. Time and time again, I found that “my” kids were not well understood. Their basic needs got in the way of education and classroom structure. Sleeping at their desk was not a sign of disrespect; it was necessary because they had been up all night with the police in their building for a drug raid. They were angry that they had to fight so hard just to get by. It made no sense to them that they had to sit still and take notes on a lecture that did not relate to them. They were hungry, tired, not sure what they would go home to, unsure as to where they would spend the night, so why did grammar matter? These students spent more time in my office, or the in-school suspension room attached to my office, than they did in class. They needed a safe space with adults they trusted. As the students got older, they spent less time in school and more time suspended or skipping class. Eventually, far too many of them vanished into the world of prison.

Do not mistake my empathy and love of at-risk kids with a tolerance for bad behavior. I expect and, most of the time, have earned superior behavior from children—it is earned not given. Early in my career in NYC, I took a weeklong trip to upstate NY to an environmental center with 100 kids and 3 teachers. I think the only reason my assistant principal agreed to the trip was because he didn’t think I could raise the money or get the extra chaperones; he was clear that schools like ours did not do overnight field trips with these kids. There were no behavioral incidents other than a little homesickness and general joy. Thank you, Dad, for chaperoning and braving the “wilderness” with me and my crazy idea.

This story of high expectations coupled with mutual respect and providing kids with the opportunity to be successful has been the backdrop of my educational philosophy. Some wonder why don’t I go back to a middle school or high school setting if I care so much? The sad truth is that educators working with poorer districts get paid the least and receive the least support. The burnout rate is high, and the hours are never-ending. As a mother, I chose a job that was more flexible, more stable, and left me emotionally able to be present at home. As an educator, I volunteer on the boards of nonprofits that work with “those” kids. Currently, I volunteer at a local juvenile prison with a group that works with incarcerated children on communication skills, and I am a guardian ad litem. This work with incarcerated youth has led me back to my passion for giving voice to and advocating for children in need. I am hoping this book sheds light on the real struggles and successes, however few, of the system that takes “my” kids.

This book explores the root causes of juvenile incarceration and issues within the juvenile system. I am not in any way suggesting that bad behavior should be tolerated, rather that the system should truly be restorative and aimed at improving lives. I have made a conscious choice to refer to the juvenile inmates and juveniles associated with the justice system as “children” because I strongly believe they are still children, both biologically and mentally.

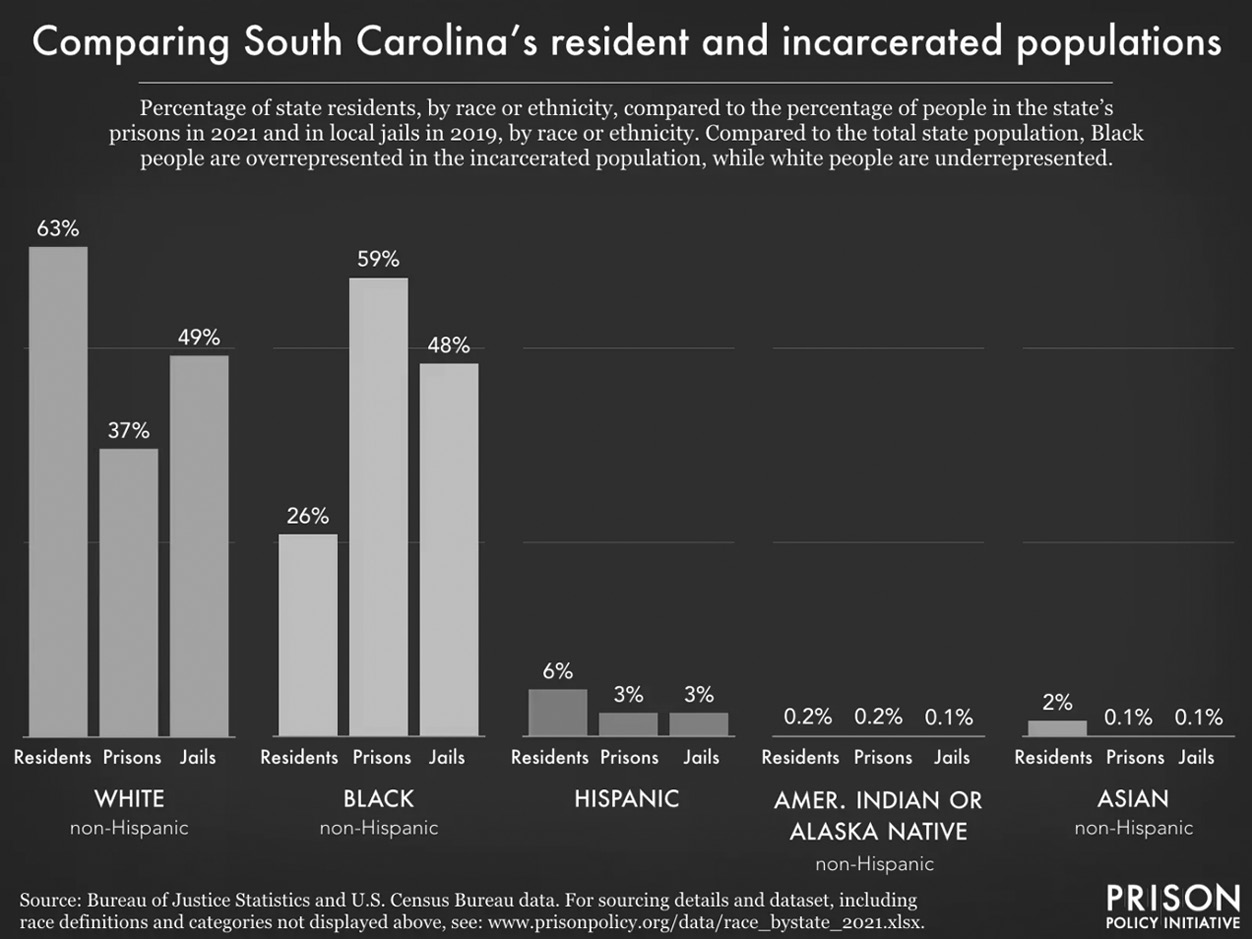

South Carolina, located in the southeastern part of the United States, had a population of 5.08 million in 2021 (Census Data USA). The median household income was $58,234, and 14.5% of the population lived below the poverty line. This Republican state was 63% White and 26% Black, according to Census Data USA. The education level of the population of the state was 3.4% GED or equivalent, 20.5% high school diploma, 14% bachelor’s degree, 5.9% master’s degree, and 0.88% doctorate.

Note: Up-to-date juvenile data is difficult to locate since reporting on minors is heavily regulated and different states use different definitions

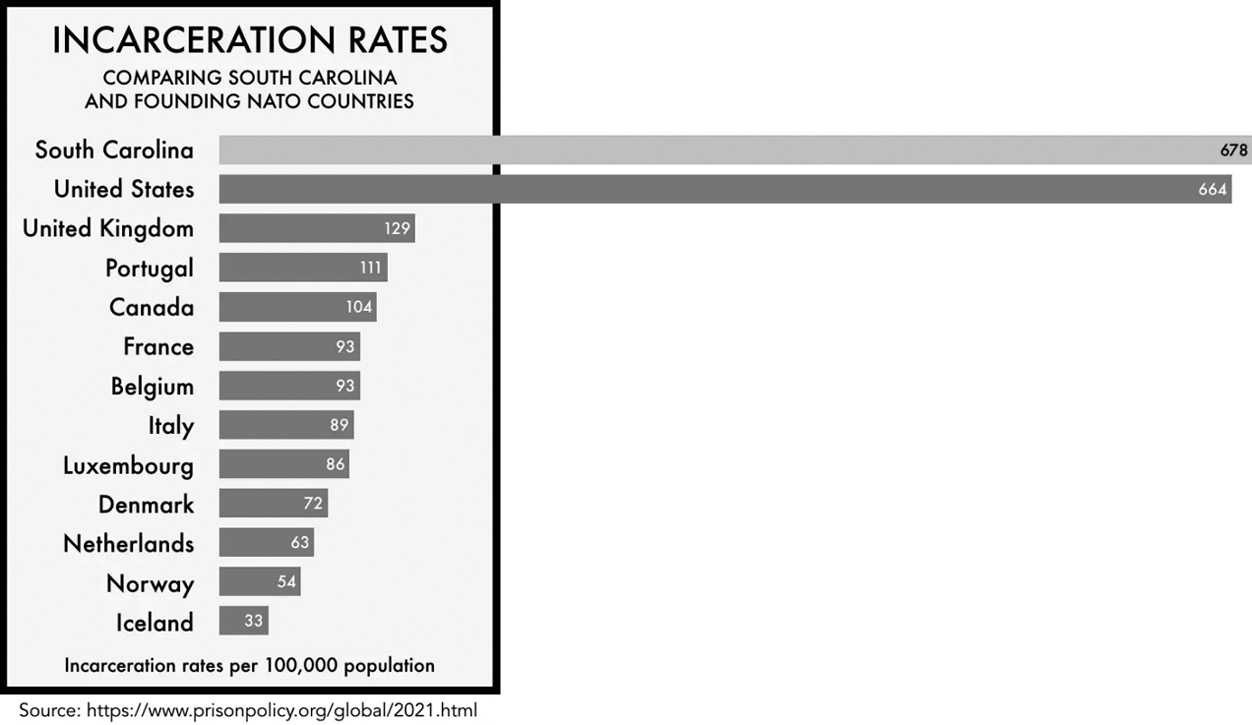

As seen in the chart, the overall incarceration rate (adults and juveniles) in the United States was 664 per 100,000 people in 2021, and South Carolina’s rate was even higher at 678.

As seen above, the percentage of Black South Carolinians in prison was disproportionately higher than that of the general population in 2021. Black citizens of South Carolina were incarcerated at a rate 3.8 times higher than White citizens (Prison Policy; Widra and Herring, 2021). South Carolina ranked #34 among U.S. states for White incarceration rates and #44 for Black incarceration rates.

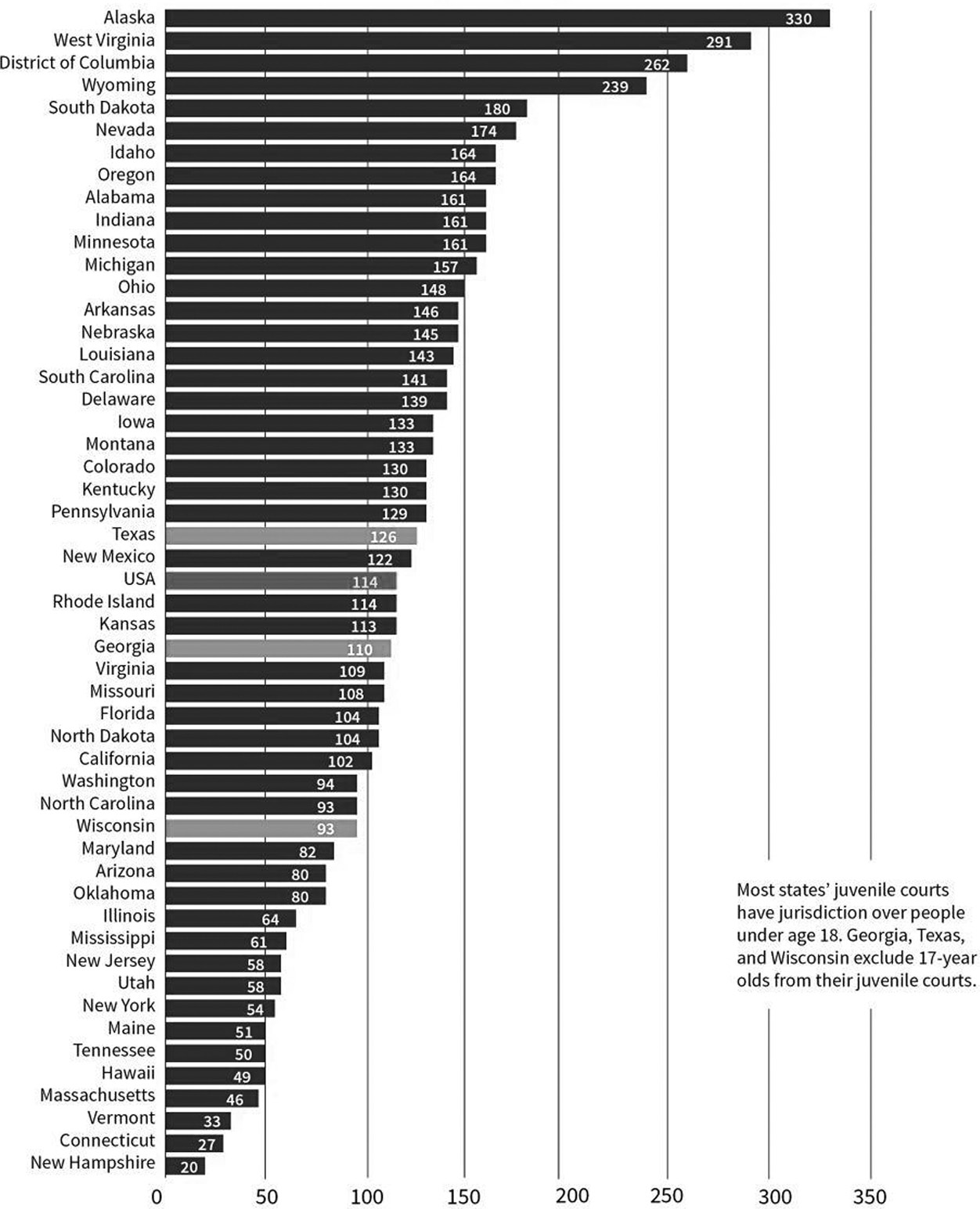

Looking at the juvenile population in South Carolina, the incarceration rate was 84 per 100,000 persons (ranking #33 among all states) compared to the U.S. average of 114 per 100,000. This average was skewed by very high incarceration rates in states such as Alaska, which had 330 per 100,000. Current juvenile statistics are difficult to obtain since states do not have the same juvenile laws and systems. Each state treats juveniles slightly differently.

Note: Youth Placement rate by state (2019). Placement rate per 100,000 juveniles.

In South Carolina, a juvenile is someone who is age 18 or younger. Someone 18 years or younger can be “waived up” to adult court based on the waiver chart § 63-19-1210. The following is a summary of the waivers:

A family court judge has the authority to waive a child who is:

- any age and charged with murder. State v. Corey D., 529 S.E.2d 20 (S.C. 2000); State v. Lamb, 649 S.E.2d 486 (S.C. 2007).

- 17 and charged with a misdemeanor, a Class E or F felony, or a felony that would carry a maximum term of imprisonment of ten years or less for an adult, after a full investigation. § 63-19-1210(4).

- 14, 15, or 16 years of age and charged with an offense that would be a Class A, B, C, or D felony or a felony that provides for a maximum term of imprisonment of 15 years or more for an adult, after full investigation and a hearing. § 63-19-1210(5).

- 14 years or older and charged with carrying a weapon on school property, unlawful carrying of a handgun, or unlawful distribution of drugs within a half-mile of a school, after a full investigation and a hearing. § 63-19-1210(9).

- A child under 14 years is prohibited under § 16-3-659 from being transferred to general sessions court on a criminal sexual conduct charge. Slocumb v. State, 522 S.E.2d 809 (S.C. 1999).

The eight “Kent Factors” are used to determine whether a waiver will be granted. The court must consider eight factors enumerated in Kent v. United States, 383 U.S. 541 (1966), before granting a motion to transfer jurisdiction, and the serious nature of the offense is a major factor in the transfer decision, see State v. Pittman, 647 S.E.2d 144 (S.C. 2007) and State v. Corey D.,529 S.E.2d 20, 26 (S.C. 2000). The eight factors of Kent are as follows:

1. Seriousness of alleged offense and whether a waiver is necessary to protect the public;

2. Whether the alleged offense was committed in an aggressive, violent, premeditated, or willful manner;

3. Whether the alleged offense was against persons or property, greater weight was being given to offenses against persons especially if an injury resulted;

4. Whether there is sufficient evidence for a grand jury to return an indictment;

5. Whether there are adult co-defendants that make it more desirable to present the entire case in one court;

6. Child’s level of sophistication and maturity;

7. Child’s prior criminal record; and

8. Prospects for adequate protection of the public and likelihood of reasonable rehabilitation of child using services currently available to the court.

The decision to “waive” children up to adult court strips some of the protections from the family court such as a focus on restorative justice. This puts children in a position to face harsher and more punitive punishments. When cases are moved to adult court, the reformative values of family court are lost.

The South Carolina Department of Juvenile Justice (SCDJJ) is responsible for providing custodial care and rehabilitation for the state’s children who are incarcerated, on probation or parole, or in community placement for a criminal or status offense. DJJ also provides a variety of prevention and intervention programs for at-risk youth. SCDJJ defines its role as follows:

DJJ has many facilities throughout the state with different purposes. The Juvenile Detention Center is a pretrial detention facility to hold juveniles pending trial. Evaluation centers hold juveniles for court-ordered evaluations after a child has been adjudicated. The Broad River Road Complex (BRRC) is for long-term commitment to serve a longer determinate or indeterminate sentence. In addition, there are alternative placements throughout the state, although it is important to note that fewer than 38% of all juveniles needing placement can be accommodated at these alternative placements. There are 218 available beds for males and only 20 beds for females in alternative placements in the entire state. The daily average population of DJJ beds is 621 (SCDJJ Data Resource Guide 2020–2021, p. 2). According to the 2020–2021 Data Resource Guide, 127 alternative beds (undefined by DJJ) are being used, serving 20% of the juvenile population in DJJ.

DJJ’s Juvenile Detention Center is a centralized pretrial detention facility serving juveniles from most of South Carolina’s 46 counties. (Several counties, including Richland and Charleston, operate their short-term detention facilities.) The Detention Center is a secure, short-term facility providing custodial care and acute treatment to male and female juveniles ages 11 to 19 who are detained by law enforcement agencies for alleged offenses committed prior to their eighteenth birthday, according to the DJJ website. A child may be in a detention center for a day, while others can be held for years, depending on the charges and how backed up the courts are. It is important to note that children cannot bond out or post bail while waiting for court like adults can. Youth ordered to cooperate with a psychiatric and educational evaluation may also be ordered by the family courts to be detained before disposition. Youth awaiting trial on serious and violent charges reside at DJJ’s Juvenile Detention Center to ensure public safety and their immediate availability for court proceedings.

In the current configuration of DJJ, there are three regional evaluation centers: Coastal, Midlands, and Upstate. Each of the agency’s evaluation centers provides court-ordered evaluations for adjudicated youth (those found guilty) prior to the final disposition of their cases. The evaluation centers provide comprehensive psychological, social, and educational assessments to guide the court’s disposition of cases. Evaluation centers also house youth in admissions status, meaning youth who are court-ordered to be committed to DJJ for a determinate or indeterminate sentence. Youth in admissions status are screened by a multidisciplinary team to determine an appropriate treatment and housing assignment. By law, the length of stay for youth undergoing a secure evaluation cannot exceed 45 days (see DJJ website).

The Broad River Road Complex in Columbia is the agency’s long-term commitment facility. The more than 200-acre complex offers programs for boys and girls of different backgrounds and needs, including programs for youth with behavioral issues and special needs.

BRRC is also the home base to DJJ’s fully accredited school district, which provides continued education for youth, preparing students for postsecondary education and beyond. The Empowerment & Enrichment Academy of South Carolina (formerly Birchwood School) is where boys and girls attend middle and high school and can also earn their GEDs. This campus also includes DJJ’s Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps (JROTC) program, a cooperative effort between DJJ’s school district and the U.S. army, and various enriching vocational programs.

In addition to school and vocational options, BRRC offers social work and psychology services, treatment planning, psychiatry services, a full infirmary for health care needs, gyms, open fields, a game room incentive building, recreation, and various types of rehabilitative programs and work programs.

Generations, Richland Country, Males, 26 beds (this is not listed on the website but was provided by DJJ in a personal communication, 2024)

According to the 2019 DJJ report card, 11,849 cases were referred to South Carolina DJJ. The number one charge referred to was third-degree assault and battery followed by marijuana possession, truancy, runaway, and contempt of court. Below is a table showing the four stages of system involvement. Referrals are youth who enter the DJJ system when they are taken into custody by law enforcement or when they are charged by a solicitor or school. Detained youth are those facing charges or those being held at a facility being formally referred. Of those cases referred, some youth are detained pending court. The average detainment is 22 days; the longest (sent to court in 2020) was 879 days (approximately 2.5 years). Evaluations happen at one of the three evaluation centers or in the community. Youth are not supposed to be held in evaluation centers for more than 45 days before trial. Commitments are those who have gone to court and received sentences.

2019/2020

Referred to DJJ |

Detained |

Evaluation |

Commitment |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Total |

1107 |

136 |

71 |

46 |

Sex |

||||

Male |

70% (n=775) |

79% (n=107) |

81% (n=58) |

84% (n=39) |

Female |

30% (n=332) |

21% (n=29) |

19% (n=13) |

16% (n=7) |

Race |

||||

Black |

55% (n=609) |

72% (n=98) |

61% (n=44) |

65% (n=30) |

White |

39% (n=432) |

21% (n=29) |

33% (n=23) |

28% (n=13) |

Other |

6% (n=66) |

7% (n=9) |

6% (n=4) |

7% (n=3) |

Age |

||||

13 and under |

16% (n=177) |

7% (n=9) |

11% (n=9) |

22% (n=9) |

14–16 |

57% (n=631) |

64% (n=88) |

68% (n=48) |

56% (n=25) |

17+ |

26% (n=288) |

29% (n=39) |

19% (n=14) |

29% (n=12) |

Referred to DJJ |

Detained |

Evaluation |

Commitment |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Most Common Offenses |

Assault 3rd Degree Marijuana Possession Truancy Runaway Contempt |

Assault 3rd Degree Weapon Carrying Pistol Runaway Armed Robbery |

Contempt of Court Assault 3rd Degree Weapon Assault 2nd Degree Carrying Pistol |

Probation Violation Felony Contempt of Court Probation Violation Misdemeanors Probation Violation Felony Weapons |

Status Offenses—only minors can be charged with these:

Per the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) with the U.S. Department of Justice, states should not detain children on status offenses. South Carolina currently incarcerates children on status offenses. Advocacy groups such as the Children’s Law Center are working to change detention for status offenses.

What disparities do you notice in the data displayed in terms of race, gender, and age? Why are 70% of referrals males and 84% of commitment males? What would explain why 55% of referrals are for Black children and 65% of commitments are for Black children?

Nationwide, there is no definition or statistics for juvenile recidivism, according to OJJDP. Snyder and Sickmund (2006) showed a 55% rearrest rate and a 24% return to confinement for juveniles within one year of release. The national average for adult recidivism is 37.1% (wisevoter.com).

Recidivism rates, with recidivism defined by SCDJJ as youth who are adjudicated for a new offense within one year of completing arbitration, probation, or commitment (SCDJJ Data Resource Guide 2022–2023), were 35.6% from 2019 to 2022 per DOJ data. Hernandez (2023) reported that South Carolina had an adult recidivism rate of 21%, the lowest in the country. Since there is no standard national definition for recidivism, this rate needs to be further explored.

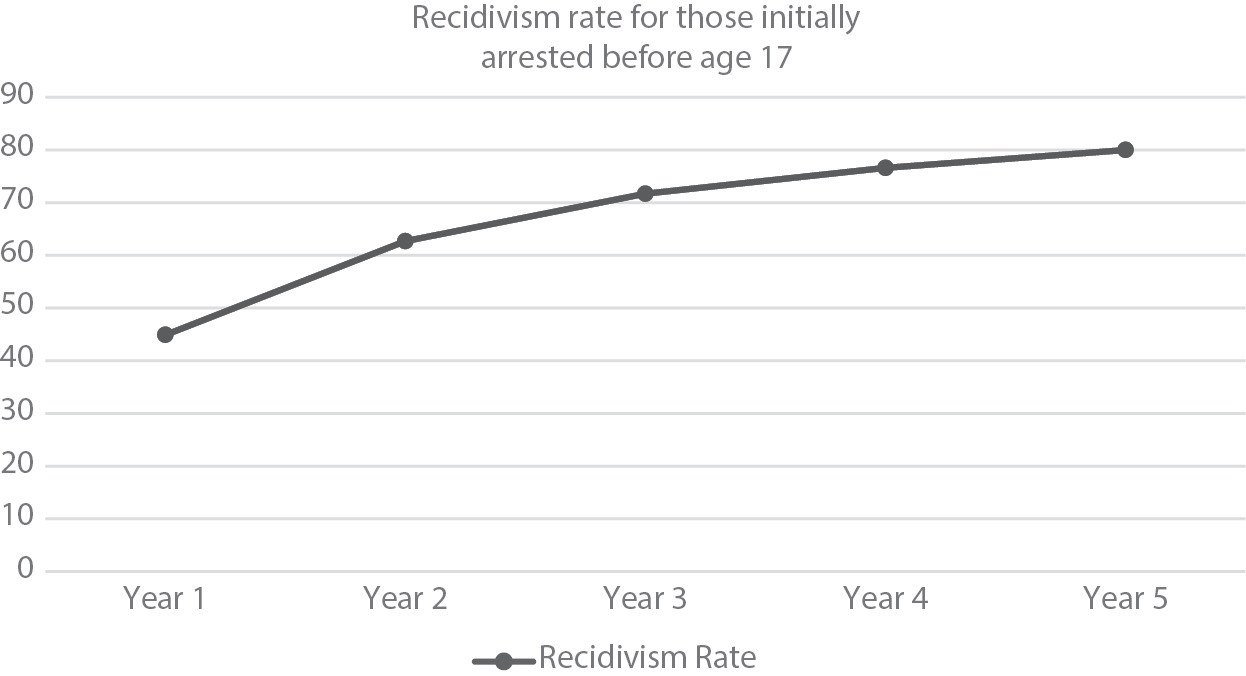

As seen above, the five-year recidivism rate can look bleak for youth. In year 1, the recidivism rate is 44.9% and by year 5, it is 80%.

In this chapter, the data for incarceration was presented. The United States incarcerates more individuals than any other developed nation. In future chapters, the book will discuss what it is like in DSS custody, how children get out of DJJ custody, and what comes next. In Chapter 1, there will be a discussion of how children enter the justice system.

1. What do you already know about the juvenile justice system?

2. What is your image of a juvenile in the justice system? Has your image changed based on the data provided?

3. What charges were you expecting juveniles to be arrested for? Which of the most common charges was surprising? Why?

4. Children as young as 11 are in the juvenile justice system. Is this surprising? What do you think about this based on 11-year-olds you know?

1. Opinion/Research—What does juvenile incarceration say about society? How do other countries handle youth who commit crimes?

2. Interview—Interview someone involved in the juvenile justice system. What is their role? How would they improve the juvenile justice system? What obstacles stand in the way of improvement?

3. Research—Look at your home state’s juvenile justice system. What is the rate of incarceration for youth? What are the alternatives in your state? What do you notice when you look at the data?