DOI: 10.3726/9781917503327.003.0006

Look out the window.

The sky’s almost covered.

Some grayish white clouds,

Some almost black.

But between them, you can see a bit of blue.

I focus on the blue.

– Léa Roback32

***

In this last chapter of Auntie Léa’s biography, I discuss the thoughts Auntie Léa shared in the interviews she gave during her eighties and early nineties. I also discuss the many tributes and honours she has received for her work and reflect on the ways her activism continues to live on in the generations of educators and activists who have followed her. While much that has been written about Auntie Léa has focused on the stories she told about her activist work in the 1930s and 1940s, I found the ideas she shared towards the end of her life about growing older as an activist very compelling. Auntie Léa’s ideas about love, family support and being grateful for beauty in the world while struggling against its ugliness offer today’s activists helpful ways of thinking about their own activist work.

In several of the interviews Auntie Léa gave in the later years of her life, she was asked if she regretted not getting married and if growing older as a single woman with modest financial means was challenging. For example, in her interview with Auntie Léa at the age of 93, Ghila Bénesty-Sroka asked Auntie Léa if she thought she had placed her political commitments above love. In response, Auntie Léa explained:

Love is very broad, you know. It all depends on what one wants to put into that word, the expectations one has. I was very busy; I had all kinds of things on my mind. I liked making love, it was very good. And then, a man’s caress, of course, is wonderful, you can’t do without it. But a husband, no (Bénesty-Sroka, 1996, p. 84).

Auntie Léa’s expansive idea of love – her understanding of love as being connected to her political commitments – was, I believe, part of what sustained her passion for activism for seven decades and why she never regretted not getting married.

The closeness Auntie Léa felt to the people she worked with, and the love she felt for them, resonates in some ways with bell hooks’ writing on love. hooks was an American Black feminist writer who drew from the writings of psychologist Erich Fromm. In her book All About Love , hooks understands love as “the will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth” (hooks, 2000, p. 4). Explaining further, hooks shares Fromm’s argument that, “Love is as love does. Love is an act of will. It is both an intention and an action. We do not have to love. We choose to love” (hooks, 2000, p. 4). In order for community love to thrive, hooks believed people need to embrace a variety of practices including care, recognition, respect, commitment, trust, and honest and open communication.

Throughout her life Auntie Léa extended herself to nurture other people’s growth. Not so much for spiritual growth (although she often told interviewers her activism was fuelled by the Jewish religious and cultural imperative to do something in the face of injustice), but perhaps for political growth. Auntie Léa worked hard to provide the people she worked with the care, recognition and respect she knew they deserved. She supported young women making hard decisions about unwanted pregnancies, protected the seniority of unionized workers, and challenged racism in hiring decisions. The people Auntie Léa worked with trusted her because she was direct and honest when she spoke to them. She had no regrets about not marrying because she had experienced love among the people she worked with in the labour and women’s movements. Her ability to embrace love within her social and political movement work not only nourished her own activism, it also sustained the lifelong activism of others, like the union stewards in the factories that Auntie Léa helped to unionize.

At the same time as she showed care and respect for the people she worked with, Auntie Léa was also very opinionated, and would express her opinions forcefully when fighting for her political values. There were people she didn’t hold much compassion for – like the factory bosses and people interested in profiteering – and, as discussed in Chapter 4, she would often confront them harshly when fighting for the rights of their workers. Although confrontation and intimidation often allowed Auntie Léa to meet her political goals, they also sometimes prevented her from doing the work she wanted to do. For example, after being fired from RCA, she would have liked to have worked in the Jewish social service sector but was considered too radical and unrelenting. She wasn’t a person who sought consensus, a skill valued in social work within the mainstream Jewish community.

Answering a similar question about growing older with modest financial means from Nicole Lacelle, Auntie Léa said:

…. It never bothered me at all. I have to say that my family has always supported me. My mother always told me that the door would always be open, that there would always be a bed to sleep in and a plate on the table. It’s an inner security when you have moral support … Like I said, I must not be normal, but I never thought that, once I was old, the sky would fall on my head. I told a friend who was worried: “We’ll think about it when we get there.”

Well, now I’m there, and my goodness, I don’t think about it much more. I don’t have money, I can’t afford to travel, but it’s not a big deal. If missing something made me unhappy, that would be a different story! … I’ve never felt insecure. Once, I had two or three dollars left, I didn’t have a job, and I spent them to go to the theatre! There’s nothing worse than being unhappy every day (Lacelle and Roback, 2005, p. 164).

When Auntie Léa would come home after a late night union meeting, she’d always find a plate on the kitchen table prepared by her mother Fanny with something “good to nibble on” and a little note saying, “I hope you are not too tired.” When she had to travel outside of Montreal, Fanny would send Auntie Léa a letter every week, and call her intercity, to ask, “What do you need? Do you want me to send you something?” (The life of a union activist: Rose Pesotta and Léa Roback, 2023). These were the days when long distance calls were expensive and were only made on Sunday evenings, after 8:00 p.m. when the rates were cheaper.

Additional family support came from Auntie Léa’s sister Annie (the sister who hosted us for lunch before the Quebec City premiere of Sophie Bissonnette’s film Des lumières dans la grande noirceur). Auntie Annie often sent Auntie Léa clothes she was no longer wearing. Auntie Léa, who loved beautiful dresses, blouses and jackets, embraced the second-hand clothing from Auntie Annie and her other sisters, telling Nicole Lacelle, “I’ve always been well-dressed with my sisters’ clothes; it was an honor because they had good taste!” (Lacelle and Roback, 2005, p. 163).

In her later years, Auntie Léa’s nephew – Edgar Goldstein – my dad, who was an oncology pharmacist at the Montreal Jewish Hospital, made sure that Auntie Léa was well taken care of. He and his wife Louise visited Auntie Léa regularly, helped her move from her apartment to a small seniors’ residence when she no longer wanted to cook meals for herself, and made sure she had the everyday things she needed, like new underwear, stockings, and shoes. Although I was living in Toronto working on my doctorate degree by the time Auntie Léa moved into the residence, I visited often. During my visits, I could see she was still living an active, engaged life.

At the seniors’ residence, Auntie Léa, who by then was in her mid-nineties, had a rigorous routine. She got up early, showered, and dressed before breakfast which she took in the dining room with the other residents. Then she went for her first walk of the day. The residence was located on a steep hill, and walking up the street kept her fit. When she returned from her walk, she’d read two daily newspapers – one French, one English. On warm days, she was able to sit outside on the small balcony to read until she was called for lunch.

After lunch, Auntie Léa would retrieve her cane and go walking again. The cane she used was first used by her grandfather, and then by her mother. It had passed through three generations of Robacks. By the time Auntie Léa got back from her second walk of the day, it was time for supper, and then after supper, in the summer, she’d take one more walk. In the winter, when it was too dark to walk after supper, Auntie Léa would go into her room and listen to the news. Auntie Léa was never a fan of television. She always called it “the idiot box.” But if my dad phoned her to tell her that there was something interesting to watch on television, she might watch it.

Right up to the time she died, Auntie Léa loved music, theatre and reading. The cultural activities that sustained her passion for life and activism in her younger years, continued to sustain her passion for life as she aged. In addition to reading two daily newspapers, she also read biographies, poetry, and the occasional novel (a copy of Marge Piercy’s City of Light, a novel about the French Revolution which I had brought as a gift was on her night table the last time we visited). Sharing her love of reading with journalist Susan Schwartz, Auntie Léa stated, “The moment you stop using your brain, you stop living” (Schwartz and Roback, 1996/1997, p. 9).

Auntie Léa also remained as political and feisty as ever. Sophie Bissonnette remembers a story about a telephone call my father Edgar received from her seniors’ residence telling him that Auntie Léa was trying to unionize their staff. They wanted her to stop. When I asked my dad’s wife Louise if she remembered the phone call from the residence, she said she did. She also remembered my dad talking to Auntie Léa about not antagonizing the people who managed the residence if she wanted to keep living there.

In celebration of one of Auntie Léa’s birthdays in her 90s, my father and Louise hosted a tea party for Auntie Léa and family who were visiting or living in Montreal. Journalist Susan Schwartz, who was writing a profile of Auntie Léa for the magazine This Country Canada in 1996, was invited to the party and was treated to good music, good food, and a beautiful view. She wrote:

After spirited piano performances by [my cousin Barbara’s] twins [Joshua and Noah] and a hearty toast by Edgar to Léa’s continued good health, the family repaired to a dining-room table, groaning with delicacies. Léa tucked in and ate with pleasure. After a time, she stared out of the dining-room window of the eleventh-floor apartment at the spectacular view of Montreal’s skyline and the St. Lawrence River to the south. “I’ve been here at night, and you see right across the river. It’s so beautiful. We’re lucky that we still have eyes that can see and appreciate this beauty. “C’est pas possible.”

“C’est pas possible” was something Auntie Léa would often say, meaning “How is it possible that there is so much beauty in this world?” Choosing to see beauty in a world that was often ugly, was one way Auntie Léa embraced optimism in both her younger and older years. As the opening quote of this chapter shows, on a day when the sky above her was covered with dark clouds, “some almost black,” Auntie Léa looked for a spot of blue. “I focus on the blue,” she told Nicole Lacelle.

When she died at the age of 96 in the summer of 2000, Auntie Léa left behind a rich legacy of activism and care that made the world a better place. That legacy has been recognized and honoured in a variety of ways. The first public recognition came in 1985, when Auntie Léa was 82 years old and became an honorary member of the Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women (CRIAW). The CRIAW wanted to recognize Auntie Léa for her social and political activism around human rights, workers’ rights, and women’s rights.

In 1993, in honour of Auntie Léa’s 90th birthday, feminist activists in Montreal established the Léa Roback Foundation, whose goal was to raise scholarship funds for socially committed and economically disadvantaged women. This honour was particularly important to Auntie Léa as it provided women without financial support the means to continue their education. She would often say, “Education is the hallmark of self-realization, and above all, a key to people’s freedom!” (Léa Roback Foundation, 2015).

To celebrate the launch of the Léa Roback Foundation and Auntie Léa’s 90th birthday, a brunch was arranged at La Maison Egg Roll, a restaurant in the working-class neighbourhood of St. Henri in Montreal. One hundred people attended, including peace activists, labour organizers, environmentalists, feminists, teachers, students, writers, filmmakers, family, and friends (Léa Roback Foundation, 2015; Schwartz and Roback, 1996/1997). An activist singing group called the Raging Grannies was invited to perform at the party, and a number of friends and colleagues brought prepared words of appreciation for Auntie Léa’s seven decades of activism and care. Raging Granny, Mildred Ryerson, who worked with Auntie Léa in the campaign for peace, told guests, “Léa represents our dreams.” Dorothy Goldin Rosenberg who was also a member of Voice of Women praised Auntie Léa as someone who had always been in the vanguard of social causes. And in the book of tributes that had been prepared for the celebration, guest Marie Mottashed wrote, “According to Jewish folklore, each generation is blessed with 36 compassionate individuals whose presence accounts for whatever goodness and justice there is in the world. I have no idea who the other 35 are, but I am certain that we have one of these select 36 in our midst” (Schwartz and Roback, 1996/1997).

Three members of my family have volunteered as members of the board which directs the Léa Roback Foundation in its work. One was Donna Mergler, whose maternal grandmother was Moishe’s sister, Lottie Roback Helfield. The second was Louise Goldstein and the third is my cousin Melanie Leavitt, who has just recently replaced Louise. The first scholarship was given out in 1994 to Linda Bherer, a nurse who used the funding to complete her degree in midwifery.

Twenty years later, Leavitt reported that in 2024 the Foundation had granted 34 scholarships totalling $85,000 to recipients from age 18 to age 67. Their educational pursuits included literacy courses, French courses for recent immigrants, high school completion courses, community college diplomas and university degrees. Each of the women who received scholarships to continue their education is using what they learned to better the lives of people in their communities. They are continuing the social justice work Auntie Léa engaged in. Auntie Léa would be absolutely thrilled.

The board members of the Léa Roback Foundation are strong fundraisers, and the amount of scholarship money they have to give out each year continues to grow. For example, in 2012, the Foundation organized a benefit concert that featured songs of struggle from Paul Robeson (1898–1976). Robeson was a popular Black American singer, famous for his Negro spirituals and folk songs, who was involved in the anti-fascist, workers’ rights, and civil rights movements in the first part of the twentieth century. Robeson toured through Europe and North America, played Othello on Broadway and sang Ol’ Man River in the film Showboat. Robeson’s activism made him a target of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) under the anti-communist politician Joseph McCarthy. Denounced as a traitor and a communist, his career was destroyed. Although he had been internationally acclaimed, he was blacklisted from performing on stage, screen, radio, and television in the United States. In 1950, the American government revoked his passport. However, after years of protest campaigns and legal action, the American Supreme Court returned his passport, and Robeson made one last concert tour. After three years of touring, he returned to the United States and retired from public life in 1963 due to ill health. He died 13 years later, at the age of 78.

The Foundation’s fundraising concert that featured Paul Robeson’s music reminded me of the people’s and workers’ concerts that Auntie Léa attended in both Berlin and Montreal when she was a member of the communist movement. Twelve years after losing Auntie Léa, the board was able to resurrect the warmth, generosity, songs, and exhilaration of comradeship that Merrily Weisbord writes about in her book The Strangest Dream to raise money for scholarships to be given out in her name.

The legacy of Auntie Léa’s activist work also lives on in Le Centre Léa Roback, a research centre in Montreal that focuses on research into social inequalities. It also lives on in Maison Parent-Roback, a hub for community groups defending women’s rights, which was established in 1997 to honour both Auntie Léa and her long-time friend and fellow activist Madeleine Parent. Maison Parent-Roback is owned and operated by ten women’s organizations. It opened on 27 September 1998, with funding from a variety of foundations. Like the scholarship recipients, each of these organizations works hard to support the communities they serve.

In 1999, on National Seniors’ Day, which takes place annually on the first of October, Auntie Léa’s work in Quebec was recognized by the Elders Council. The following year, in April 2000, the YWCA honoured Auntie Léa at its Women of Distinction gala, once again alongside Madeleine Parent. Then, in May 2000, just a few months before she died, the Quebec government inducted Auntie Léa as a Knight of the National Order of Quebec. I attended the ceremony where Auntie Léa was given a certificate, a ribbon, and a medallion – posthumously – for her outstanding achievements. I framed the certificate, and it now hangs on a wall in my office at the University of Toronto, where I talk to my students about Auntie Léa’s life and work.

I passed on the ribbon and the medallion to my cousin Lea Goldstein, who was named after Auntie Léa, on the occasion of her bat mitzvah. Lea is my Auntie Léa’s great-great-niece and the great-granddaughter of my grandmother Rose. Lea’s bat mitzvah took place on Zoom during the Covid lock-down. During the reading of her Torah portion, Lea sat behind a table with a tablecloth that held her reading and Auntie Léa’s ribbon and medallion. It was a moment full of meaning for Lea and her family: on the day she became a young woman responsible for deciding how she would like to practice Judaism, Lea chose to remind herself of her great-great-aunt Léa’s legacy of working towards social justice. Of course, Lea will find her own ways to work toward social justice in the different communities she is part of, and they may be different from the causes her great-great-auntie Léa adopted. But like so many others, I know that Lea will be inspired by her aunt’s incredible courage, persistence, and optimism, as she finds her own way to make the world a better place.

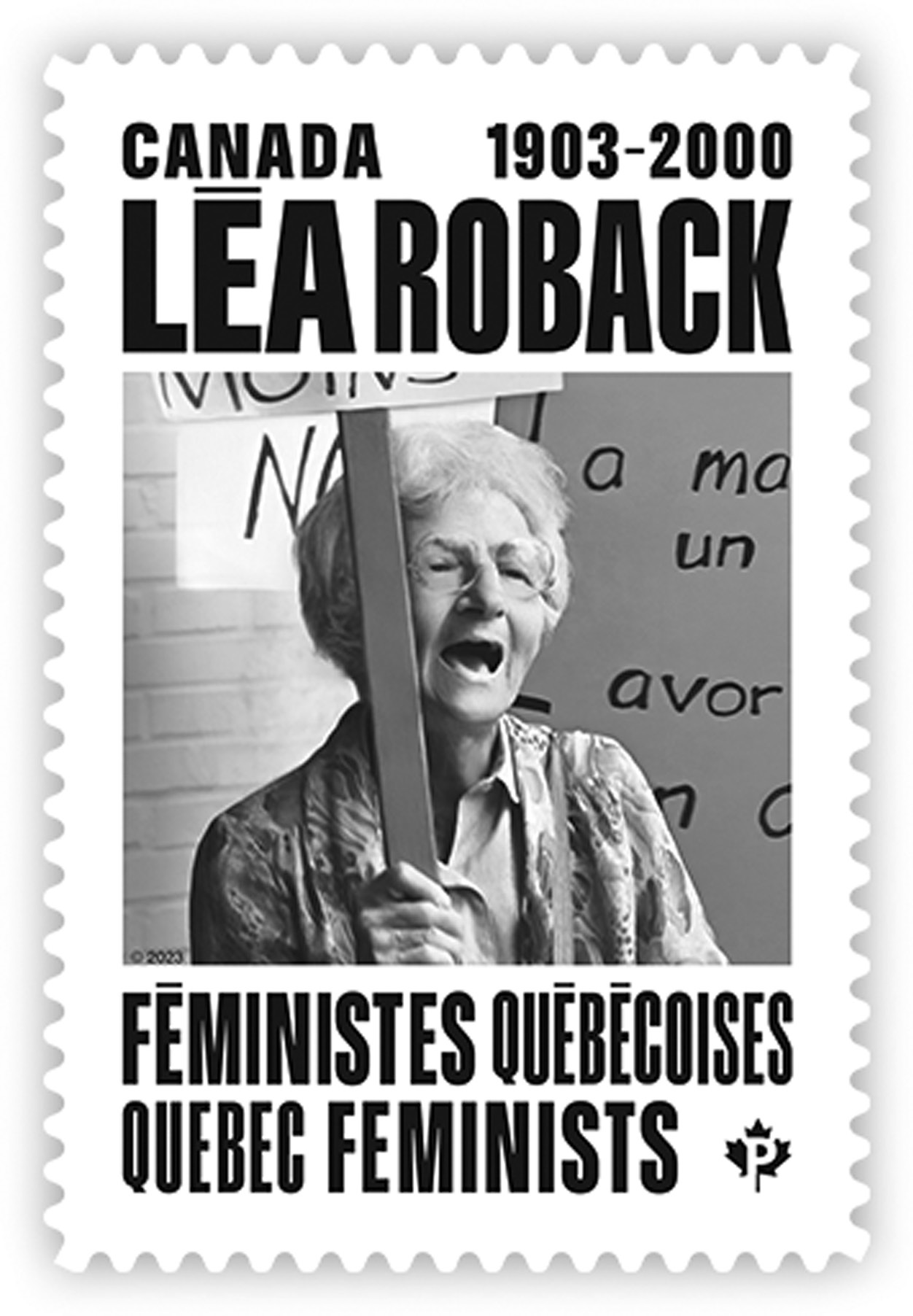

In addition to having been named a Knight of the National Order of Quebec, Auntie Léa has had a street named after her in her childhood home of Beauport, a park named after her in the city of Côte Saint-Luc on the island of Montreal, and another street named after her in the Montreal neighbourhood of Saint-Henri. Rue Léa Roback (Léa Roback Street) in Saint-Henri is not far from where the original RCA plant was located in the 1940s. Most recently, in August 2023, Canada Post released a stamp celebrating Auntie Léa alongside two other stamps honouring Quebec feminists: Madeleine Parent and Simone Monet-Chartrand.

While I was unable to attend the ceremony in Montreal that celebrated the release of the stamp, I video-recorded a message to be played at the gathering and received a full report of the event from my cousin Melanie Leavitt who was there. It was after hearing Melanie’s description of the joy and excitement that accompanied the way Auntie Léa and her fellow activists Madeleine Parent and Simone Monet-Chartrand were being honoured that I began thinking about writing this story of Auntie Léa’s life and activism. In closing my biography, I’d like to share one of my strongest memories of spending time with Auntie Léa.

In 1973, when I was fourteen, Auntie Léa took me to a summer theatre festival located in Stratford, Ontario. I was supposed to go to the Stratford Festival with my grandmother Rose, but she died unexpectedly in March, just before my brother Richard’s bar mitzvah. My grandmother was adored by everyone in the family – as well as by everyone who knew her – and we were all devastated.

Auntie Léa knew that it was my grandmother Rose who had introduced me to live theatre. Rose took me to see a French puppet show with her when I was about five or six. The show was sold out, and my grandmother had to put our names on a waiting list. When she went to speak to the box office clerk, she spoke in French. Like Auntie Léa my grandmother was completely fluent in French, English and Yiddish and could cross language borders easily. My grandmother told the box office clerk that our last name was Gauthier (not Goldstein). When I asked her why, she said that we were more likely to get to the top of the waiting list with a French-Canadian name like Gauthier than with an English, Jewish name like Goldstein. I don’t know if she was right or not, but we did get two last-minute seats under the name Gauthier. The experiences of the Roback family with antisemitism in Beauport and Montreal in the first decades of the twentieth century encouraged my grandmother to use her skill as a fluent speaker of French to border cross between her own English Jewish community and the French-Canadian theatre community.

Like Auntie Léa, my grandmother Rose also worked for His Majesty’s Theatre. It was Auntie Léa who got her a job there. Rose also sold tickets to performances put on by the Montreal Children’s Theatre (MCT), a children’s theatre company founded in 1933 by Dorothy Davis and Violet Waters. She reserved tickets for my brothers and me, and we attended many MCT performances. Then when I was seven or eight, my grandmother enrolled me in drama classes at MCT so I could audition for roles in the school’s annual production. During the time I took classes at MCT I played the roles of a villager in The Pied Piper and a fairy in Cinderella.

After my grandmother’s sudden death, Auntie Léa volunteered to take me to Stratford so I wouldn’t miss seeing the plays my grandmother had planned for us to see. Travelling from Montreal to Stratford, Ontario with Auntie Léa involved a train ride from Montreal to Toronto, an overnight stay in Toronto, a second train ride from Toronto to Stratford, booking a room in someone’s home as bed and breakfast guests, and then walking to each of the three theatres where the plays were held. Auntie Léa and I did it all. We saw three plays: Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew (a play about sexism), Othello (a play about racism – the same play that Paul Robeson starred in on Broadway), and a Canadian play by Henry Beissel called Inook and the Sun, which actually had its premiere at the 1973 Stratford Festival we attended.

Despite the wonderful theatre we saw during our trip to Stratford, my clearest memories from the trip are not about the plays we saw but all of the other things we did together. I remember going to the health food store to get lunch for our picnics in the park (it was the first time I had ever shopped in a health food store). I also remember attending a folk music concert at a club called The Black Swan (it was my first time going to a club to hear music late at night). And I remember eating breakfast at the Woolworth’s lunch counter and Auntie Léa ordering breakfast in French. The teenage server, who lived in English-speaking Stratford, did not understand a word Auntie Léa said. Auntie Léa told the server, a little harshly, that because she lived in a bilingual country, she needed to learn to speak French. The server who had never been told anything like that before, and who was likely a little intimidated by Auntie Léa, nodded silently. I remember being grateful that my parents had enrolled me in a French immersion program when I was in the seventh grade and that I was currently taking forty percent of my courses in high school in French. Unlike the English-speaking server at Woolworth’s in Stratford, I could read, write, and speak French even though I was a student in an English-speaking school in Montreal.

My trip to Stratford with Auntie Léa was not only a trip full of theatre, but a trip full of health food, folk music, and politics. At fourteen, I was introduced to ways of travelling and being in the world that were different from anything I’d ever experienced before. Culture – all kinds of culture, from Shakespeare to 1970s folk music, to Inuit fables – brought joy and pleasure. The kind of joy and pleasure that sustained Auntie Léa and her comrades in difficult times as activists.

A few years later, when I was in my twenties, I followed Auntie Léa and my grandmother Rose into theatre box office work. I was a university student at Concordia University studying English Literature and Women’s Studies (which had not yet been renamed Women and Gender Studies) and worked part-time selling tickets at the English-language Centaur Theatre in Montreal. In the summer, I worked at an English-speaking Canadian summer theatre festival held at Bishop’s University in Lennoxville, Quebec, a two-hour drive from Montreal. Many years later, after establishing a career as a researcher and teacher at the University of Toronto, I completed a master’s degree in playwriting at Spalding University in Louisville, Kentucky. In 2007, at the age of 50, I founded an independent activist theatre company called Gailey Road Productions.33 Based in Toronto, Gailey Road is a place where “research meets theatre and theatre meets research.” I write research-based and verbatim theatre plays that when read aloud or performed, provide opportunities for conversations around discrimination, human rights, and activism. For example, my most recent project, The Love Booth and Six Companion Plays , is a set of seven short plays about histories of queer and trans activism and care in the early Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Liberation movement (Goldstein, 2023).34

For readers who haven’t heard the term before, a verbatim play is created by researching what people have to say about their everyday lives or about an event that has happened in their community (Brown and Wake, 2010; Goldstein, 2023). The words of these people (for example, the words of the activists I researched) are then edited, arranged, and/or recontextualized to form a dramatic monologue or play script, which can be performed on stage by actors who take on the characters of the real individuals whose words are being used (Hammond and Stewart, 2008).

The first play in my project, The Love Booth, tells the story of lesbian activists Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen who became partners in life and a created a family of choice that supported their activism in the early 1970s to delist homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association (APA)’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The six companion plays tell the stories of other moments of activism and other families of choice created by queer and trans activists and their allies. They include stories of activism undertaken by gay men to support the presidential campaign of Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman to run for President in the United States in 1973; the activist work done by Iris de la Cruz to challenge the stigma and shame of living with HIV in the 1980s; the creation of Kitchen Table –Women of Colour Press by Black lesbian poet Audre Lorde and Black scholar and writer Barbara Smith; the poetry writing of Two-Spirit artist and activist Chrystos which was published in Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa’s groundbreaking 1981 book This Bridge Called My Back; and the activism of trans activists Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and Chelsea Goodwin to provide shelter for homeless young drag queens, gay youth, and trans women living in New York. Gailey Road staged a production of The Love Booth and Six Companion Plays for the Toronto Pride Festival in 2023. The performance provided me, the director, the cast, and the audience with the same kind of joy and pleasure Auntie Léa had received from the theatre performances she attended.35

I first began thinking about writing a biography about Auntie Léa’s life and activism after the stamp created in her honour was released in the summer of 2023. I began conducting archival research at the Jewish Public Library in Montreal in January 2024, and began writing in May 2024, in preparation for attending my first Biography International Conference. I thought I would get more out of the conference if I started to write the biography before the conference began. The conference was held in New York City, and I was able to get a ticket to the Broadway musical Suffs, a play about the American suffrage movement by theatre artist Shaina Taub. Knowing that I would be researching Auntie Léa’s participation in the Quebec suffrage movement, I thought it would be inspirational to see and hear how Taub staged moments of the suffragists’ activism on stage.

The show was sold out the night I saw it. We were an enthusiastic audience. The theatre was filled with young people, many of them young women, some of whom had come with their mothers and grandmothers. In May 2024, Americans were preparing to vote in a national election, and the audience was eager to hear stories about the nineteenth- and twentieth-century activists who fought for women to have the right to vote. At the end of the play, the entire cast came out to sing a song that sounded like a call to activism from the suffragists on stage to the people in the audience. The song was called “Keep Marching” and the chorus went like this:

Cause your ancestors are all the proof you need

That progress is possible, not guaranteed

It will only be made only if we

Keep marching, keep marching on …

… Yes, the world can be changed

We’ve done it before

So keep marching, keep marching

(Taub, 2024).

The idea that progress is possible, but not guaranteed is an idea that Auntie Léa knew to be true. What Auntie Léa also knew to be true was that the only way progress could be made is by marching and protesting against discrimination and inequality. Auntie Léa spent her life marching and protesting. She provided proof to her nephews and nieces and all of the young people who followed her that the world could be changed – but only if they kept marching. I hope this biography of Léa Roback’s activist life of community love and care inspires you to keep marching, in whatever way you think is needed. And when times get tough, I also hope it inspires you to focus on the blue.