DOI: 10.3726/9781918026054.003.0008

The term ‘neurodivergent’ refers to an individual or individuals whose neurodevelopment differs from those considered ‘neurotypical’, that is, those whose neurodevelopment is considered normative, while the term ‘neurodiverse’ describes a collective of mixed neurotypical and neurodivergent brains (Pellicano & Den Houting, 2022). Societal understanding and acceptance of the neurodivergence movement is increasing, and this is reflected in scholarly research and contemporary policymaking. However, the lived experiences of mothers and birth parents identifying as neurodivergent (commonly Autistic and ADHD [attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder]) are largely missing from the literature. In this chapter, I discuss the importance of lived experience research in terms of increasing knowledge and awareness and the implications for informing policy. I finally discuss mediating the various challenges of bringing lived experience methodologies into my PhD research.

Key words neurodivergence, autism, mothering, childbirth, and lived experience

(Charlton, 1998, in Barnes, 2020)

The experience of childbirth and parenting is transformative for all new parents; however, for some, it can be a time of trepidation and uncertainty. Disabled birth parents often experience additional barriers to those faced by non-disabled parents. Redshaw et al. (2013) note that women with disabilities often experience multiple oppressions and forms of discrimination, restricting their ability to achieve full societal participation. While the literature on parenting neurodivergent children is abundant, the lived experiences of parents identifying as neurodivergent is scarce (Redshaw et al., 2013).

While the topic of neurodivergence is slowly gaining traction in academia, health settings and within the wider public sphere, understandings and reactions vary and are frequently contested (Kapp, 2020). However, in recent years, the landscape has shifted towards understanding neurodivergence in social terms of human rights and identity as opposed to a pathological deficit in need of treatment and cure. Similar to the critical disability and mad studies movements, ‘a politics of neurological diversity recognises power inequalities between people differently situated in relation to neurology, comparable with social stratifications such as class, gender, and ethnicity’ (Rosqvist et al., 2020). Viewed through a neuroaffirming lens, lived experience is centred and hegemonic views of neurodivergence are countered and resisted.

My PhD thesis entitled ‘The lived experiences of neurodivergent birthing people in Australia: A qualitative, reflexive analysis’ focuses on the lived childbirth and parenting experiences of birth parents identifying as neurodivergent. It aims to better understand the experience of neurodivergent mothers and families and to amplify the voices of a marginalised and often misunderstood group. In this chapter, I aim to discuss the existing – albeit sparse – research on the lived childbirth and parenting experiences of neurodivergent (Autistic and ADHD) mothers/birthing parents. I then discuss the concepts of insider and participatory research, noting the benefits and challenges of each. I finally discuss ways in which I aim to mediate the challenges of producing insider and participatory research as a PhD researcher and examine the implications for policymaking.

The term ‘neurodiversity’ was coined collaboratively in 1998 by sociologist Judy Singer, journalist Harvey Blume and other members of an autism advocacy email list, and was thereafter incorporated into the lexicon of the fledgling autism advocacy movement (Kapp, 2020; Pellicano & Den Houting, 2022). Its original meaning was simply an acknowledgement of the diversity in human brains, broadly conceptualising such varied conditions as autism, ADHD, Tourette’s syndrome, dyslexia and dyscalculia under its umbrella. In some conceptions, it also includes conditions such as schizophrenia, hearing voices, bipolar, Down syndrome and dementia; however, this is contested (Kapp, 2020). The neurodivergence paradigm rejects the biomedical model’s notion of neurodivergent conditions as biological impairments and deficits, instead building upon the social model of disability which understands disability as the result of an environment whose structures create barriers for people with impairments (Oliver, cited in Watson & Vehmas, 2020). The term ‘neurodivergent’ refers to an individual or individuals whose neurodevelopment differs from those considered ‘neurotypical’, that is, those whose neurodevelopment is considered normative, while the term ‘neurodiverse’ describes a collective of mixed neurotypical and neurodivergent brains (Pellicano & Den Houting, 2022). The contemporary neurodivergence paradigm considers the complex intersections and structures that both disadvantage and benefit neurodivergent individuals in a myriad of ways. It advocates for a framework of social inclusion that acknowledges people’s differences and agentic capacity as individuals, whilst celebrating the unique and diverse societal contributions of neurodivergent brains (Kapp, 2020).

However, the neurodiversity movement has faced some critique from academics, health professionals and parents of Autistic children for being ‘unrepresentative and divisive’ (Kapp, 2020, p. vi). Two of the primary arguments made by opponents are that it is not inclusive of people with more significant impairments, whilst some stanchly constructivist social science and humanities academics have suggested the movement is biologically reductionist. A third argument asserts that the terms ‘neurotypical’ and ‘neurodivergent’ are divisive and dichotomising, enabling an ‘in group’ and ‘out group’ mentality (Russell, 2020, p. 288). A full exploration of the critiques levelled at the neurodiversity movement are outside the scope of this chapter. Suffice to say that my positionality as a neurodivergent researcher aligns with that of the neurodiversity movement, which not only makes compelling arguments about the nature of neurological diversity and its implications for scientific research and understanding, but champions the notion of societal inclusivity eschewing the imperative of the medical model of disability to find a cure for this perceived deviance/deficiency (Kapp, 2020; Pellicano & den Houting, 2022). For those of us who have spent a lifetime feeling strange or deficient, the neurodiversity movement offers the hope of acceptance and equity. daVanport (2019, p. 150) writes:

Out of Searching Came Community: neurodiversity soon became something that I intimately understood as the all-inclusive acceptance of every neurological difference without exception. I further came to appreciate that neurodiversity didn’t leave anyone out. Even the opponents of this concept reaped the benefits of the work by neurodiversity activists. It didn’t matter whether they agreed with the concept or not, they personally benefited. Furthermore, their children did as well, as the specific premise of neurodiversity is full and equal inclusion.

The personal is indeed political, and as numerous academics, advocates, and others have noted, it is possible to be cognisant of the disabling societal barriers neuronormative society presents to neurodivergent people, acknowledging the wide diversity in neurodivergent conditions and presentations, while simultaneously being committed to a paradigm shift in terms of societal understandings of neurodivergence. Following other social justice movements, the neurodiversity movement recognises the importance of an intersectional approach which understands that neurodiversity is compounded by other forms of societal oppression such as race/ethnicity, class, gender and sexuality, and works to ameliorate these oppressions (Kapp, 2020; Giwa Onaiwu, 2019). It is therefore imperative to amplify the voices of neurodivergent people, particularly those from further marginalised communities.

The ways in which historical societal conceptions of neurodivergence, and particularly autism, have shifted over the course of the last 100 years have been extensively documented. Steve Silberman’s (2016) influential historical analysis of Autism, Neurotribes, discusses in depth the varying medical and societal paradigms that have dominated Autism psychology, research and practice. In the twentieth century, these ranged from explicitly eugenicist discourses (p. 120) and parental blame (p. 206) to harsh behavioural modification techniques based on psychological methods of operant conditioning (p. 305–310). By the turn of the twenty-first century, a myriad of pseudoscientific alternative treatments were offered as potential ‘cures’ (365). Common to all these is the prevailing notion of autism as a ‘debilitating’ and undesirable condition (p. 283) in need of intense management in the hope of overcoming and eliminating Autistic behaviours. The rise of the neurodiversity movement (p. 501–504) has empowered and emancipated Autistic people and their families from bleak and paternalistic conceptions of autism to the idea that Autistic people can live fulfilling, autonomous lives that don’t depend on hopes of recovery (p. 504).

However, notions of ‘curing’ autism persist. Garcia (2021) discusses problematic contemporary societal discourses, including criminally profiling Autistics and spreading misinformation. He notes that three quarters of research funding in America goes towards discovering the ‘root causes’ of autism and the ‘best ways to treat’ Autistic people, while only 6% is used for improving services and supports (p. xiv). Donald Trump has been quoted as spreading misinformation and disinformation in terms of the (debunked) connection between vaccination and autism, and furthermore, referring to autism as an ‘epidemic’ (p. xii). Trump’s rhetoric, as stated on Twitter and CNN, extended to his presidential campaign:

On April 2, 2017, Trump’s presidential proclamation for World Autism Day read “My Administration is committed to promoting greater knowledge of [autism spectrum disorders] and encouraging innovation that will lead to new treatments and cures for autism.”

It is with all this in mind that I commenced my PhD research focusing on the lived experiences of birth parents identifying as neurodivergent. I have undertaken sociological research in the past in the field of childbirth, maternity care and birth trauma, so that is familiar territory. After discovering my own neurodivergence whilst completing a qualifying social work master’s degree and working in the field of disability support, I became increasingly interested in the birth and parenting experiences of neurodivergent mothers/birthing people; in fact, I would regularly find myself musing about doing a PhD on the topic. I aim to contribute to the sizable gap in the scholarly literature on the lived experiences of these parents in terms of their own experiences of neurodivergence rather than that of parenting their neurodivergent children, of which there is much written. My positionality as a mother who has given birth twice and who identifies as ‘AuDHD’ (Autistic and ADHD) aligns with the concept of ‘insider research’, in which the researcher is a part of the community under investigation and possesses a level of knowledge of the community and its members due to lived experience (Greene, 2014; Kirpitchenko & Voloder, 2014). As Pellicano and Den Houting (2022) note, previous research in the United Kingdom reveals that Autistic people and their families have been frequently disappointed in research projects in which they have felt objectified and devoid of agency, often having little to no access to the results of the study in which they participated. It is thus crucial to situate research and policy objectives in contexts that are not only meaningful to neurodivergent people and communities, but which engage neurodivergent people as researchers and coresearchers.

I knew very little about participatory research initially; however, upon doing further reading, I was fascinated and wanted to incorporate this into my thesis. Nevertheless, given the various structural constraints of postgraduate research – and the fact I was already well into my second year and had already changed topic and supervision team once – I decided after discussing the matter with my supervisors to remain with my original (well, revised) traditional qualitative research model conducting semi-structured interviews with twelve to fifteen neurodivergent mothers/birth parents recruited mostly from various neurodivergent-focused Facebook groups. That said, my objective is to utilise my insider status reflexively to attempt to negotiate the research process in order to afford participants as much opportunity as possible to amplify their voices and to have meaningful input.

My aims and research questions are:

• To understand the lived experiences of an often-marginalised group, whilst being mindfully aware of differences in identity perception and understandings of what constitutes being ‘disabled’.

• To illuminate areas in which neurodivergence is useful or life-enhancing.

• To exert reflexivity regarding the researcher’s insider status to assist in amplifying the voices of participants.

• To uncover policy gaps and make salient recommendations for inclusive policymaking.

This latter point is important because it connects research focused on lived experience to policy, reframing the ‘problem of autism’ (Stace, 2011) in terms of the human rights and support needs of Autistic individuals, as stated by Autistic people themselves.

Throughout this paper, I utilise the ‘identity-first’ term ‘Autistic’ or ‘Autistic person’ rather than the increasingly outdated ‘person-first’ term ‘person with autism’ as preferred by some scholars and clinicians, to reflect the preference of the majority of the Autistic community (Chown, 2017; Kapp, 2020). In line with this, I capitalise the identity-first proper adjective ‘Autistic’ as it pertains to Autistic individuals as a mark of respect as noted by autism advocacy organisation Amaze (2024). I will, however, use person-first terms when directly citing an author or text. Similarly, I will use ‘ADHDer’ or ‘AuDHDer’ when discussing my own experiences; however, as the majority of the published literature used ‘person/people with ADHD’, I will use that language for purposes of clarity.

Considering the multiple barriers to autism and ADHD diagnosis in Australia (Senate Community Affairs References Committee, 2023; De Broize et al., 2022), I wanted to ensure that participation in my research was as equitable as possible; hence, recruitment criteria states that participants may be professionally or self-diagnosed.

Language used to describe pregnant people/women and mothers/parents will alternate between gendered terms (women, mother) and gender-diverse terms (birthing person, birth parent) to best facilitate inclusion.

There is extensive interdisciplinary research on childbirth and parenting worldwide. Despite varying opinions on the best methods for childbirth and parenting, it is generally accepted that everyone has the right to a safe birthing environment where they can exercise agency and control. Disabled birth parents often encounter additional obstacles to this objective. The World Health Organization (2022) reports that disabled individuals frequently face stigma and other barriers in the healthcare and maternity care system, including insufficient knowledge or negative attitudes from healthcare providers, discrimination and inaccessible facilities. These issues can lead to feelings of exclusion, otherness and a lack of trust in healthcare providers and systems – factors essential for a positive birthing experience.

The existent literature on people with ADHD is negligible, while that on neurodivergence comprising of two or more (multiple) neurodivergences is non-existent. Scarcely any attention is given to the lived experiences of birth/birthing parents who identify as being both Autistic and ADHD – commonly and colloquially known as ‘AuDHDers’ (Hinze et al., n.d). This constitutes a monumental gap in the research, which my current research aims to rectify! This is crucially important, considering the rapidly increasing prevalence of diagnosis and/or identification of mixed neurodivergence both in Australia and globally (Sutherland, 2024). It is imperative for policymakers to ‘hear’ the voices of neurodivergent birthing people, particularly considering recent parliamentary inquiries such as the Select Committee on Birth Trauma (Parliament of NSW, 2023). Various experiences of birth trauma have been apparent in the literature on neurodivergent birthing experiences (Stuart & Reynolds, 2024; Donovan, 2020). The consultation draft of the ‘National Autism Roadmap’ (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, 2024), despite an extensive consultation and codesign process with Autistic adults, pays scant attention to the needs of Autistic parents other than in their capacity as carers of Autistic children. Due to this lack of mixed identification/dual diagnosis in the literature and policy, this section first considers the sparse literature on mothers/birthing people with ADHD, before moving on to the research on Autistic mothers/birthing people.

Despite having a reported prevalence of 2.5% in adults worldwide (Walsh et al., 2022), research on birthing people with ADHD is scant. What exists is drawn primarily from the disciplines of obstetrics, medicine, nursing or psychology, and commonly framed through a pathological deficit model that focuses attention solely on risks and health complications associated with the condition. Walsh et al. (2022) acknowledge the paucity of research in the perinatal period, arguing that this requires remediating considering ADHD is associated with a variety of comorbidities. This includes ‘depression, anxiety and accidents’, placing those with the condition at greater risk of negative life outcomes with increased likelihood of mental health issues ‘associated with increased pregnancy and birth complications’ (Walsh et al., 2022 p. 2). Their study revealed higher rates of every medical condition that was tested for in patients with ADHD, with the authors highlighting the importance of this for informing clinicians treating such patients. Additionally, Walsh et al. (2022 p. 2–3) assert that there is an increased likelihood of women with ADHD, who are taking stimulant medication, experiencing unplanned pregnancies. This issue is explored by Poulton et al. (2018) who note that while ADHD stimulant use and prescribing was low during pregnancy (3.5%), stimulant use was associated with ‘small increases in the risk of some adverse pregnancy outcomes’ (p. 377). A report by Krewson (2023) cited an increased risk (24%) of mothers with ADHD of developing postpartum depression compared to those without ADHD, while Fuller-Thomson et al. (2016) state that women in general with ADHD were three times more likely to experience conditions, including chronic pain, insomnia, generalised anxiety disorder, suicidal ideation and experience sexual abuse. Additionally, they note that these women are twice as likely to experience ‘substance abuse, current smoking, depressive disorders, severe poverty and childhood physical abuse in comparison with women without ADHD’ (p. 918). Finally, Samuel et al. (2022, p. 309) observe the potential of recent improvements in autism awareness to similarly inform the needs of women and birthing people with other neurodivergent conditions such as ADHD.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition (DSM-5)) defines autism as ‘Persistent deficits in communication and social interaction across multiple contexts’ (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 50). It is considered to be a lifelong neurodevelopmental difference; however, diagnosis requires symptoms to have been present from childhood. In the DSM V, the term ‘autism’ is used to cover the entirety of pre-DSM V diagnoses, including Asperger syndrome, autism spectrum disorder and pervasive developmental disorder, among others (Chown, 2017). The prevalence of autism is hard to establish due to barriers to diagnosis and changing understandings of the nature and presentation of autism (De Broize et al., 2022); however, Australian Bureau of Statistics data recorded 164,000 Australians with an Autism diagnosis in 2015, an increase of 42.1% since 2012, with the vast majority of those diagnosed being young males (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020). However, while there are currently no figures available on the number of Autistic parents in Australia, it is likely that actual numbers are higher. This is possibly due to lack of autism awareness among healthcare providers and financial and other barriers to diagnosis and healthcare faced by Autistic adults in Australia (Arnold et al., 2024; Rasheed, 2023).

Research on Autistic mothers and birthing people is scant, although this is beginning to change. Existent literature reveals a range of strengths and challenges common to Autistic birth parents in terms of both childbirth and parenting experience. Autistic mothers have often been reluctant to disclose their autism to health professionals, citing concerns of negative judgement and stigma (Pohl et al., 2020). A study by Lum et al. (2014) revealed that 75% of participants who revealed their diagnosis had received a negative response, while participants in the research by Hampton et al. (2022) felt professionals were dismissive of their experiences. Hampton et al. identified additional challenges for Autistic mothers in terms of communication and sensory barriers as well as deficits in health professionals’ understandings of autism. Sensory sensitivities are common in Autistic adults, with research indicating prevalence at over 90%. Autistic women have reported greater sensory sensitivities than both non-Autistic women and Autistic men (Samuel et al., 2022). Talcer et al. (2023) note that pregnancy heightened the sensory sensitivities of some study participants with such aspects as foetal movement, nausea and heightened visual processing considered distressing.

Sensory experience of light, sound, touch and smell were often heightened in participants in four qualitative studies reporting a significant increase in anxiety throughout childbirth, as discussed in a systematic review by Samuel et al. (2022). Hampton et al. (2022) note that some Autistic participants found the sensory environment of the hospital more stressful than the physiological experience of pain (p. 1168) and found the postnatal maternity ward replete with noise of visitors and crying babies challenging. Some mothers experience sensitivities or aversion to sensations associated with breastfeeding; however, according to Pohl et al. (2020), the majority of Autistic mothers (80%) in their study were able to successfully breastfeed.

Communication issues emerged as another prevailing theme in the literature. Many study participants found communication with professionals difficult due to factors such as lack of autism awareness, perceived negative judgement and communication differences between neurodivergent and neurotypical people. While the medical model argues that Autistic people experience impairments in social communication, the ‘double empathy problem’ theory arising from a social model perspective argues that neurodivergent and neurotypical people have different communication styles, resulting in difficulty empathising with one another (Mitchell et al., 2021). Autistic women have commonly reported a lack of clear, direct communication from health professionals during pregnancy and childbirth, resulting in misunderstandings, confusion and experience of significant anxiety (Pohl et al., 2020; Hampton et al., 2022).

Several recommendations have been made regarding better ways to support Autistic mothers and birthing people in the perinatal period based on the experiences of these mothers. These include such factors as a need for clear communication, improved continuity of care and vastly improved understanding of the sensory and communication needs of Autistic people. Talcer et al. (2023, p. 846) suggest supporting pregnant Autistic people with occupational therapy to develop ‘tailored sensory strategies’, further noting that lack of accommodation of Autistic individuals’ needs should be viewed as contrary to the Disability Discrimination Act (2010). Hampton et al. (2022) argue for sensory accommodations during childbirth such as dimming of lights, noise reduction, providing a private room where possible and increased awareness among health professionals not only of some of the challenges, but also of the strengths Autistic people possess. This may include in the maternity provision context, increased aptitude for knowledge and research enabling better childbirth preparation and understanding of their own sensory and other needs resulting in the development of coping strategies (Talcer et al., 2023). Better understanding of support needs and improved neurodivergence awareness could significantly reduce the anxiety and overwhelm Autistic women frequently report in maternity services. This is especially crucial given the greater likelihood Autistic mothers face of experiencing both antenatal and postnatal depression (Samuel et al., 2022).

Similar to childbirth, Autistic mothering/parenting is an under-researched area; however, the existing research reveals that there are similarly challenging aspects reported. These may include the following:

– Problems in terms of communicating with professionals

– Fear of negative judgement by professionals and others

– Sensory and tactile difficulties when parenting their children

– Lack of, or conversely, overemphasised bodily awareness

– Intense overwhelm and fatigue

– Executive functioning issues

– Isolation and loneliness

– Experience of stigma and dismissive attitude

Several strengths were also noted, including enhanced connection with their Autistic children, lack of concern for the attitudes of others and better understanding of the challenges their Autistic children may experience (Sutcliffe-Khan et al., 2024). For many parents of Autistic children, discovery of their own autism follows their child’s diagnosis, and several parents have reported subsequent ‘focused interest’ on parenting and neurodivergence as a means of gaining knowledge that was invaluable in terms of parenting decisions. Parents also noted a feeling of connection with and acceptance by their children and increased insight into their children’s lived experience (Sutcliffe-Khan et al., 2024).

Parents reported that some of the intense demands of parenting could be overwhelming and isolating. The imperative to socialise more and put their children’s needs for (for example) socialisation ahead of their own needs (possibly for solitude and quiet) was often perceived as difficult, and parents reported the increased need to ‘mask’ their autism in social settings (Sutcliff-Khan, 2024; Pohl et. al., 2020). This can be exceedingly tiring and contribute to overall levels of fatigue and overwhelm. Autistic mothers were more likely to find motherhood an isolating experience due to lack of connection and feelings of difference (Pohl et al., 2020). This could be especially profound in settings such as parent groups and when needing to communicate with their children’s health professionals and educators (Pohl et al., 2020; Sutcliffe-Khan et al., 2024). Two of the key themes in a study by Thom-Jones et al. (2024) examining Autistic women’s experience of motherhood on social media platform Reddit were ‘Autistic mothering is different’ and ‘Autistic mothers need Autistic mothers’ (p. 5). Autistic mothers’ interactions with other Autistic mothers engendered feelings of normalisation and validation and a sense of solidarity (pp. 5–7). The informal peer support garnered in such settings appears to be invaluable in terms of increasing connection and decreasing loneliness (Thom-Jones et al., 2024).

Together, this existing research on birthing and parenting demonstrates a significant need for the specific needs of birthing people to be further researched and for researchers and policymakers to jointly engage in a process of co-production and design with Autistic birthing people. The ‘Report on research, codesign and community engagement to inform the National Roadmap to Improve the Health and Mental Health of Autistic People’ (Autism CRC, 2024, p. 9) engaged with a range of stakeholders which included 125 Autistic people, of whom ‘56 of the parents, carers or guardians of Autistic people also identified as Autistic’. They produced twenty-five recommendations, recommendation twenty of which states:

Develop and establish national evidence-based standards in pain measurement for Autistic people, considering intersectional experiences and identities across diverse settings such as bedside care, ambulance transport and childbirth, ensuring applicability across all ages and abilities.

While most of the report refers to general healthcare services, several findings and recommendation in this report are highly salient to the maternity context. These include challenges relating to:

– Differences in pain perception and interoception

– Experience of [medical and other] trauma

– Executive functioning difficulties

– Being disbelieved by medical professionals

– Issues around informed consent

– Wishes being ignored

– ‘Competing life demands, including parent/carer responsibilities’

– Sensory issues within the healthcare environment

There is clearly scope to develop this type of consultation and codesign process further in terms of more specific recommendations aimed specifically at birthing people.

Insider research, which occurs through a process of positionality, involves intentionally aligning one’s self-interests with one’s research.

Insider research is research conducted within a social group of which the researcher her/himself is a member (Greene, 2014). It originates in ethnographic field research arising from the disciplines of sociology and anthropology. Insider research is concerned with the researcher’s positionality and social location (Green, 2014). As such, the researcher is ‘imbricated within the research and possesses an a priori intimate knowledge of the community and its members’ (Wilkinson & Kitzinger, 2013, p. 251). While insider research has a long history, its use in autism research is a recent development.

Kirpitchenko and Voloder (2014) note the existence of a long-standing dichotomy in social science research between insider and outsider research (p. 3). Distinctions of ‘Insider-Outsiderness’ are predicated on socio-demographic categories of the researcher in comparison to the research group participants – for example, age, gender, ethnicity, social class, sexual orientation, and as of recently, neurodiversity – although as Den Houting et al. (2021, p.148) note, ‘participatory autism research is still rare’. Moreover, participatory ADHD research appears absent from the literature. Some scholars argue that insider researchers possess the advantage of inherent knowledge and understanding of a particular group, while outsider researchers possess the necessary distance to question taken-for-granted assumptions (Kirpitchenko & Voloder, 2014).

Influential sociologist Robert Merton (1972) critiqued the notion that only insiders can truly understand the social and cultural nature of a group, arguing that while insider perspectives hold valuable and unique insight, they should not be the only perspectives offered in the research process. The notion of an insider-outsider dichotomy has been strongly contested. Insider status would be better conceptualised as being on a continuum as opposed to a binary and comprises of total insiders, who share multiple identities or profound experiences with the community they are studying, and partial insiders , who share a sole identity with a certain extent of distance or detachment from the community (Greene, 2014, p. 2).

As Merton suggested, neither an insider nor outsider position is superior to the other. That said, there is a strong argument that insider-led research conveys particular benefits. These include:

Insider positionality may confer disadvantages as well as advantages. Researchers may find forming professional boundaries difficult, which can compromise ethical integrity, compromise the study results and result in overwhelming the researcher in circumstances in which participants have additional expectations of them as a community member. Managing relationships, both professional and personal, may be challenging, and bias may occur in terms of participant selection.

Insider research has been oft-critiqued as being too subjective and bias laden (Chavez, 2008; Greene, 2014; Kirpitchenko, 2014). This is particularly true in disciplines such as psychology which is, as Wilkinson and Kitzinger (2013, p. 251) assert, ‘deeply committed to a concept of objectivity that treats insider research as contaminating the production of knowledge’. The same has traditionally applied in sociology, with classical sociologists such as Georg Simmel arguing that the production of knowledge by strangers is more transmissible and superior in terms of scientific rigour (Kirpitchenko & Voloder, 2014). However, as feminist and standpoint scholars have argued, a traditional positivist paradigm seeks to generalise experiences, negating individuality and deep, rich data collection, and ‘denying the power of diversity’ (Kirpitchenko & Voloder, 2014, p. 5). Moreover, as previously stated, positionality is not binary, nor is it static. Identity cannot be reduced to one sole position; rather, researcher identity must be considered in an intersectional manner that recognises the multiple and diverse intersecting identities of both the insider researcher and the research participants (Couture et al., 2012). Several scholars have discussed their personal experiences of negotiating the insider research experience and have suggested numerous ways in which potential pitfalls may be avoided or minimised (Wilkinson & Kitzinger, 2013; Kirpitchenko & Voloder, 2014).

Participatory research (PR) is research that is carried out with participants as co-producers of knowledge. It is performed with them rather than on them (Cornwall & Jewkes, 1995). Vaughn and Jacquez (2020) define it as an umbrella term for methods that collaborate with those individuals or groups directly affected by the issue being studied. PR prioritises the co-constructing of research partnerships between researchers and community groups, individuals and other stakeholders not necessarily trained in research methods, engaging in a process of ‘sequential reflection and action’ (Cornwall & Jewkes, 1995, p. 1667). Participatory research primarily differs from conventional, top-down approaches to research by focusing on issues of power and control, aiming to disrupt hegemonic institutional power structures, and conduct research that is more equitable and democratic, involving participants as coresearchers in the decision-making process (Cornwall & Jewkes, 1995; Vaughn & Jaquez, 2020).

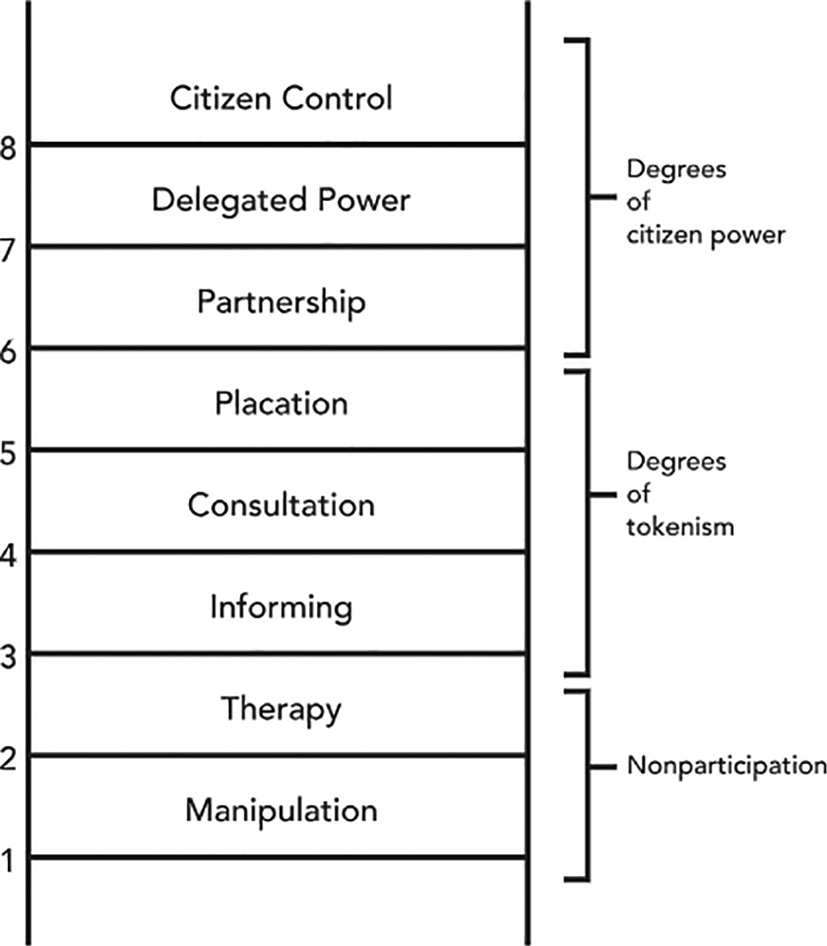

Despite a significant increase in autism research during the last few years, use of participatory models is still rare in terms of autism research (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019; Den Houting et al., 2021). Den Houting et al. state that despite calls from Autistic academics for more community co-produced research projects, truly equitable research remains uncommon. These are frequently limited to involving community stakeholders in advisory or consultative roles (p. 149). Cornwall and Jewkes (1995) note that there are several ‘models’ of participatory research ranging from those limited to consulting with communities/individuals through to those based on a Freirean pedagogical model of active participation in creating change. The various levels of participation can be conceptualised using Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation, which ranks participation levels from ‘non-participation’ (manipulation and therapy) through to ‘degrees of tokenism’ (informing, consultation, placation) to ‘Degrees of citizen power’ (partnership, delegated power, citizen control) (Arnstein, 1969).

‘Arnstein’s ladder’

However, Fletcher-Watson et al. (2019, p. 944) note some critique of this model for, among other issues, its lack of acknowledgement that ‘participation itself can be a goal and the process and diversity of experience matter as much as outcome’. They further state that the ladder remains a useful tool for conceptualising power dynamics in autism research, asserting that the majority of research affords either little or merely tokenistic forms of power to participants. Den Houting et al. (2021) note some challenges in terms of conducting participatory research, including the need to balance academic rigour with community participation, the complex nature of managing relationships and greater financial costs; however, they argue that the benefits of community participatory models outweigh its challenges. Similarly, Pellicano et al. (2022) note that not only does PR hold emancipatory power for individuals and communities, but it stands to improve the methodological, scientific and ethics of autism research.

As previously mentioned, incorporating a participatory research approach is something I would have loved to have included in my PhD research; however, systemic and other barriers have precluded this. Nevertheless, I fervently hope that my insider research can include some authentic (if minor) level of co-production (Southby, 2017). Cornwall and Jewkes (1995) argue that rather than methods, researchers’ attitudes form the fundamental element of participatory research and that PR is characterised by the location of power (pp. 1667–1668). Researcher reflexivity is an essential component of both insider and participatory approaches (as well as within qualitative research in general). Participatory research is informed by the concerns and values of the community being investigated. As Pillow (cited in Kirpitchenko & Voloder, 2014, p. 5) asserts, being a self-reflexive researcher means not only contributing insider knowledge to research, but also providing ‘insight on how this knowledge is produced’. Additionally, the use of autoethnography in terms of incorporating ‘self-narrative’ or ‘personal anecdotes’ (p. 10) in one’s methodology can be a valuable tool in terms of ‘the vulnerability and the humanity of the researcher in relation to a broader social context’ (Kirpitchenko & Voloder, 2014).

While it is important to avoid the risk of essentialising insider status to a single homogenous entity, a notion of shared identity can facilitate a sense of belonging, engendering rapport between researcher and participants with the potential to disrupt traditional power relations. Whilst it is crucial to retain strong professional boundaries, I conduct interviews by always considering participants’ needs first, ensuring that there are alternatives in terms of meeting place or communication style (e.g. some participants may prefer text-based conversations, others meeting in person, or Zoom); additionally, where appropriate, I like to include discussion of ‘what is needed’ in terms of healthcare facilities, policy or future research. In my personal experience, many people in the AuDHD space welcome the chance to have their thoughts and opinions noted, and most of my participants have expressed interest in staying informed and connected to the project.

Southby (2017) discusses their PhD research into the experiences of people with a learning disability in football participation in the United Kingdom, noting the ‘spectrum’ of participatory research in which participation can occur at ‘different levels and in unpredictable ways’ (p. 130). They reflect upon the challenges of doing participatory research as a research degree student, noting the multiple barriers inherent in the process. While certainly not impossible, practical methodological considerations, such as the structure of a PhD and the proposal process requiring such aspects as the formation of research questions before acceptance into a PhD programme, along with the necessarily rigid ethical procedures, make this difficult. Southby notes that these barriers to doing a participatory PhD may be overcome if the researcher is ‘already embedded in the field’ in which they wish to research (p. 134). They state that while they would have preferred for their research to be situated further along the participatory continuum, the need to adhere to university protocol to obtain their PhD precluded this; however, they were happy that some level was achieved (p. 139).

The examples discussed throughout this chapter have emphasised the importance of insider, participatory and codesigned research as crucial to understanding the lived experience of neurodivergent individuals. This research, in turn, is vital in terms of informing policy. Recent co-produced research undertaken in partnership with the Australian government informs a report intended to develop a policy ‘Roadmap’ addressing problematic aspects of healthcare provision for Autistic people in Australia (Autism CRC, 2024). This report reveals similar themes to the existent scholarly research on the lived experiences of neurodivergent mothers. Understanding these challenges and implementing recommendations in a policy context is of crucial importance; however, structural challenges contribute to the scarcity of participatory methodologies in empirical neurodivergence research.

Research methodologies led by neurodivergent researchers are vital to promoting inclusivity and studies conducted through a participatory or co-production lens facilitate meaningful and emancipatory opportunities to amplify the voices of a marginalised community or group. While participatory methods, in particular, present some challenges, the benefits are copious. It would benefit neurodivergent researchers, communities and policymakers if institutional barriers to participatory research were addressed systemically, particularly in terms of funding and the structural processes of PhD and postdoc/early career research. It is hoped that my current PhD research might begin to fill the significant gap in terms of research into the experiences of neurodivergent parents and that future research and policy might address salient areas of need in terms of healthcare and community and social services.