DOI: 10.3726/9781916704206.003.0001

Singing and dancing female figures dominate the make-shift stage characteristic of outdoor performances of ludruk theater. The sounds of the accompanying gamelan music played on an ensemble largely comprised of metal keyed instruments and gongs pierce the air through an enormous sound system: interlocking octaves pop; lines of melody sparkle; powerful drum strokes articulate the dancers’ delicate yet powerfully precise movements. The incessant “chrings” of their ankle bells add a layer of color, life, intensity, and magic. Some watching whistle with delight and desire; others whisper their wonder. While some of the dancers are perhaps in their thirties, ripe in their sexuality, others are older, exuding a more mature womanliness no less stunning. While some are slender and others are not—some shy, some coy, some confident, some detached—each interprets the drumming in their own way as they dance not quite together with the others; their femininity engulfs, mesmerizes, and arouses despite the maleness of their bodies.

A tayub event is no less remarkable. Rows of guests, mostly men, sit at long tables awaiting their turns to request a song and dance with the female singer-dancers who have been hired to entertain them. The women have enhanced their beauty by carefully applying thick false eyelashes; drawing exquisite mustaches above their full, red lips; and donning wigs of neat, short hair. Seemingly unimpressed by the guests when they perform, the dancers move to the sounds of the gamelan with a strong sort of grace, their lolloping head rolls and martial-arts-like moves enhanced by bass drum and cymbal crashes, the gamelan supplemented with a keyboard to appeal to the tastes of audiences who enjoy popular forms of music. Despite the masculinity that the movement and music evoke, the powerful womanliness of the dancers’ figures and voices overwhelms. An earthiness permeates the damp, humid air already heavy with snaking tendrils of cigarette smoke, already pregnant with the smells of cloves, tobacco, mud, alcohol, and sweat.

* * *

Come! I invite you to delve into males’ embodiment of femininity and females’ embodiment of masculinity in the cultural region of east Java, Indonesia, where I conducted field research on dance and its accompanying gamelan music and where I visited over the course of 2004 to 2015, with a period of intensive fieldwork spanning 2005 to 2007. Captivated by the fashioning of femininities and the making of masculinities, I have been inspired to write about the negotiation of gender through dance performance (Sunardi, 2009; 2011; 2013; 2015; 2020; 2022). My admiration of the artists I consulted and saw perform continues to fuel me as I build on my prior work to offer this intentionally short book meant for use in undergraduate courses. As such, this book addresses the questions:

1. How is gender a cultural construction that people continuously produce, reproduce, contest, challenge, alter, and so on—in short, negotiate?

2. How can we understand processes by and through which individuals negotiate gender through the performing arts and their lived experiences as artists in specific cultural contexts?

I offer answers to these questions—recognizing that these are not the only answers—by establishing my analytical and methodological approaches in this chapter and, in the following two chapters, by centering the lived experiences and perspectives of six dancers in the east Javanese regency of Malang. I argue that through both their onstage participation in cross-gender dance performance and through their offstage lives they contributed to the cultural production of gender, and in doing so, they contributed to the production of local place-based identity. Chapter 2 focuses on ways in which two men and one waria (a male who dresses and lives as female) produced complex senses of gender through the performance of female-style dance since the mid-twentieth century. Chapter 3 presents three women who produced complex senses of gender through the performance of male-style dance through the course of the twentieth century (perhaps since the late 1890s) and into the twenty-first. In addition to onstage–offstage implications, themes that link Chapters 2 and 3 include gender fluidity, gender pluralism, and spirituality. Chapters 2 and 3 are framed by learning objectives and questions for discussion. These questions are very much meant as a place to start and I encourage you to develop additional questions for discussion, reflection, and additional research. I conclude the book with some closing words, and then suggest discussion questions pertinent to the entire book as well as project or assignment ideas. A short list of recommended further readings follows the list of references at the end of the book, although I do recommend every source in the reference list as well! But before we get to all of that, let’s get our bearings.

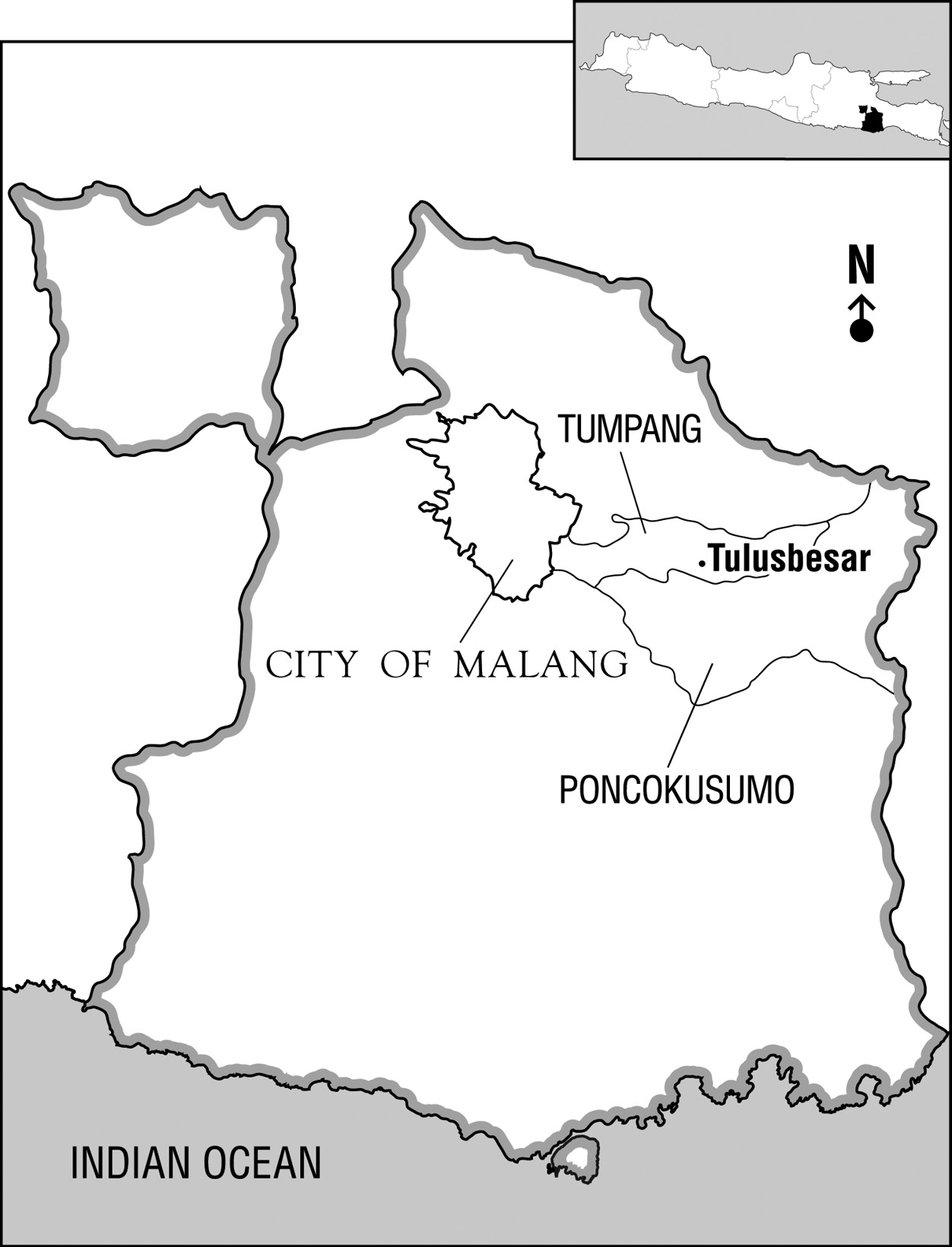

Malang is a regency (kabupaten ; analogous to a county in the Unites States) and city in the cultural region of east Java, one of several cultural regions within the Indonesian province of East Java (Figure 1). Unless I specify otherwise, I am referring to Malang as a whole—the city and regency together—when I write Malang. I use the approach of the ethnomusicologist R. Anderson Sutton (1985; 1991) to distinguish national political divisions from cultural regions as the two do not always match: lower-case letters refer to cultural regions (such as east Java and central Java) while upper-case letters refer to names of Indonesian provinces (such as East Java and Central Java). The traditions of music, dance, and theater that musicians and dancers referred to as east Javanese are rooted in the central part of the province of East Java, including the cities of Malang, Mojokerto, Jombang, and Surabaya and their surrounding areas (Sutton, 1991, p. 121; Sunardi, 2010, pp. 89, 120n3; 2015, p. ix; 2017, p. 65; 2020, p. 448; 2023, p. 8; in press). Banyuwangi at the eastern tip of Java and the island of Madura to the north each have their own traditions of performing arts (Sutton, 1991, pp. 121–122; Crawford, 2001, p. 329). As one moves west from Malang, the performing arts traditions become increasingly similar to those of central Java. When performers in Malang spoke about central Javanese arts, they were usually referring to the arts associated with Surakarta within the province of Central Java, sometimes including Yogyakarta in the Special Region of Yogyakarta (Sutton, 1991, pp. 19–68, 121; Sunardi, 2010, p. 89; 2015, p. x; 2017, p. 65; 2023, p. 11). I resided about 23 kilometers east of the city of Malang in the village of Tulusbesar (or Tulus Besar), studying gamelan music and dance primarily with artists in the subdistricts of Tumpang and Poncokusuma, and also interviewing performers and observing performances in the city of Malang (Figure 2).

Map showing Malang as well as provinces, special regions, and selected cities of Java. Map drawn by David Wolbrecht, © 2013 University of Washington.

Map showing the village of Tulusbesar, the subdistricts of Tumpang and Poncokusuma, and the city of Malang within the regency of Malang. Map drawn by David Wolbrecht, © 2013 University of Washington.

Malang was a stimulating place, visually and culturally. I regularly saw breathtaking hills and mountains, including an active volcano visible in the distance, agricultural fields, apple orchards, rivers, streams, ruins of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century temples, ducks, chickens, goats, cats, dogs, small horses, and more, all of which constantly reminded me of the importance of the land and animals in sustaining life and culture in the area over the centuries. The diverse ethnic makeup, including Javanese, Chinese, Madurese, and various multi-ethnic people and families contributed to a rich multi-cultural fabric. Religious diversity was no less noticeable. While predominately Muslim, Christianity was also present—one of my teachers was Catholic. Hinduism was also practiced, particularly in the Tengger mountain communities that span the regencies of Malang, Pasuruan, Probolinggo, and Lumajang (Hefner, 1985, p. 44). Javanese spiritual beliefs and practices were very present, sometimes comprising part of what the anthropologist Timothy Daniels refers to as the Islamic spectrum in Java to capture the variety of approaches to Islam, ways of being Muslim, and ways of expressing Islamic piety in Java (2009). Indeed, spirituality is a theme that permeates this book.

I found the people I met and worked with in the village environments of Tumpang and Poncokusuma to be quite cosmopolitan. Most were fairly current on national and international events through television, newspapers, word of mouth, and, for younger generations, social media. Those interested in fashion and celebrity gossip were also up to date on those matters. Cell phones and texting were a regular part of life, particularly for the younger people. People in Tumpang and Poncokusuma frequently traveled to the city of Malang for various reasons, such as to work, shop, attend school, and for fun. Many had also traveled to other parts of Java, other parts of Indonesia, and/or to other countries for various reasons, including to work and to visit family. Some had family members who had traveled. I met or heard about a few people who had made the haj, the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca (Sunardi, 2015, pp. xv–xvii). It was in the dynamic context of Malang as a place with its stunning beauty and engaging individuals that I had the privilege of studying local styles of performance.

Malang as a place was critically important to most of the 60 or so performers I consulted, including dancers, musicians, and puppeteers/masked dance narrators. Most consistently emphasized their performance practices, traditions, and identities as Malangan—a distinct substyle and identity within east Java. Within Malang, they distinguished styles and ways of performing music and dance associated with different areas, and differences within areas at the levels of villages and in some cases individuals (Sunardi, 2010, pp. 89, 90–91; 2015, pp. xxii–xxiii).

Many voiced concerns that their local styles of performance (music, dance, theater) would disappear as they were replaced by the more popular and prestigious traditional styles from central Java and Surabaya and by genres of popular music. Such genres of popular music included dangdut , which features electric guitar(s), bass, keyboard(s), and drums at its core, often with flute (Frederick, 1982; Manuel, 1988, pp. 210–211; Yampolsky, 1991; Weintraub, 2010), and campur sari , which combines gamelan instruments with electric keyboards, bass, and guitar, among other instruments depending on the group (Brinner, 2008, p. 19; Supanggah, 2003; Cooper, 2015). The artists I consulted in Malang felt that their arts had been marginalized, underrepresented, and, due to audience preferences and demands for central Javanese, Surabayan, and popular forms, local Malangan styles would eventually vanish (Sunardi, 2010, pp. 93–94; 2015, pp. 22–25).

The artists I worked with were thus heavily invested in preserving their local styles of performance, which they sought to do in part by working with me—having me document their traditions and their experiences and taking this material to share with others in the United States through my writing and teaching as a professor, which indeed I have done my best to do. One significant takeaway from my fieldwork—from listening to performers—is that the production and representation of gender through dance performance was integrally connected to performers’ senses of their local, place-based identities. In other words, I found that the production of gender and place-based identity were intricately connected, one informing the other, as performers strove to maintain Malangan styles of music, dance, and theater as distinct substyles within the cultural region of east Java. This point, a key component of the main argument of this book, builds from the argument in my first book that through changes performers made to tradition, they negotiated culturally constructed boundaries of gender and sex (2015, p. 1) as well as my attention to the production of senses of place and local identity through the performing arts (2010; 2015; 2017; 2020; 2023).

My thinking about the roles of the performing arts in the production and representation of place-based identities has been enriched by the work of Martin Stokes, R. Anderson Sutton, and Zoila Mendoza, among other scholars. Martin Stokes, an ethnomusicologist, argues that “music and dance … provide the means by which the hierarchies of place are negotiated and transformed” (1994, p. 4). He goes on to write that music (and dance, I add) are “socially meaningful not entirely but largely because [they provide] means by which people recognize identities and places, and the boundaries which separate them” (1994, p. 5). The anthropologist Zoila Mendoza investigates dance troupes’ performances during patron saint festivals in Peru as a form of ritual dance that produces complex senses of identity in relation to notions of place, history, ethnicity/race (one complex category), gender, generation, and class (2000). Similarly, R. Anderson Sutton, also an ethnomusicologist, focuses on multiple senses of identity produced through performance as he investigates South Sulawesians’ presentations of themselves as belonging to a region, as a particular ethnicity, as modern, and as part of the Indonesian nation through dance and music (2002). In earlier work on gamelan traditions in different regions of Java—including in east Java and Malang—he examines expressions of place-specific identity through analysis of performance practice and institutions, work that I have extended in my analyses of Malangan and east Javanese gamelan performance practices (Sutton, 1985; 1991; Sunardi, 2010, pp. 91–92; 2011; 2015; 2017; 2020; 2023).

The performing arts that I studied in Malang fall into what performers categorized as “traditional” (tradisi), including gamelan music and dance accompanied by gamelan music. Gamelan are ensembles comprised largely of gongs, keyed percussion instruments, and drum(s) (Figure 3). Vocal parts may also be used and sometimes featured, and other instruments such as zither, bowed fiddle, and bamboo flute may also be used. Gamelan ensembles of various types can be found on the Indonesian islands of Java, Madura, Bali, and Lombok. Similar types of ensembles are played in other areas of Southeast Asia as well, such as piphat in Thailand, pinpeat in Cambodia, saing waing in Myanmar/Burma, and kulintang in the Philippines (Kalanduyan, 1996; Spiller, 2008, pp. 23–38; Douglas, 2010). In Java, the metal that is usually preferred for the gongs and metal keyed instruments in a gamelan is bronze, although iron and brass, which are less expensive, may also be used (Brinner, 2008, p. 3). As indicated, there are different regional styles, and different styles within regions.

This photograph shows several instruments of a gamelan ensemble. Photograph taken by the author, 2006.

Among other purposes, gamelan music in Java is used to accompany dance, including forms of masked and non-masked dance, dance events called tayub or tayuban in which professional female entertainers are hired to sing and dance for a host’s guests, hobby-horse dance events that often feature dancers going into a trance (jaranan), and various forms of theater, including shadow puppet theater (wayang kulit), masked dance drama (wayang topèng), and ludruk, a form of east Javanese theater that features a variety of opening acts and a main play or drama. Performing art forms such as these are typically sponsored by a host (which could be an individual, a family, a community, a business, and so on) to celebrate a certain occasion, such as a wedding, the circumcision of a boy marking his transition to manhood, the opening of a business, an anniversary (such as the founding of a community or organization), a holiday, an auspicious day on the Javanese calendar, and village-cleansing ceremonies. Music, dance, and theater may also be featured at festivals and competitions, and in other contexts.

This book focuses on the dances Beskalan, Ngremo (Ngrema, Ngrémo, Remo), and masked dance, which exist in both male (lanang, putra, pria) and female (putri, wanita ) styles. Male-style dances are characterized in general by wider stances, higher arm positions, and larger movement volumes than female-style dances (Figures 4 and 5). Male-style dances include Beskalan Lanang, Ngremo Lanang (also referred to as Ngremo Putra, Ngremo Pria), and masked dances that portray males. Female-style dances include Beskalan Putri, Ngremo Putri (also referred to as Ngremo Wanita), and masked dances that portray female characters. Beskalan, Ngremo, and masked dances may be performed as opening or welcoming dances for other performances or events—such as an opening dance for a puppet performance, ludruk, or tayub (although typically when an opening dance is used for tayub it is Ngremo). Masked dances may also be performed in the context of masked dance drama. Ngremo dancers often sing in the course of performing the dance, welcoming audiences and/or guests and singing a form of poetry called parikan , such as the epigraph of this book, among other texts (Sunardi, 2015, pp. 17, 51-54, 81-82; 2023). While historically Beskalan dancers also sang in the course of performing the dance, this had largely fallen out of typical practice at the time of my fieldwork and visits to Malang (Sunardi, 2015, pp. 127-157).

The dancer Tri Wahyuningtyas poses in a position from the male-style dance Beskalan Lanang in costume. Photograph taken by the author, 2009.

The dancer Wahyu Winarti poses in a position from the female-style dance Beskalan Putri in costume. Photograph taken by the author, 2006.

Male-style dances in Java are not exclusively performed by male dancers and female-style dances are not exclusively performed by female dancers. The dancer Tri Wahyuningtyas, posing in a position from the male-style dance Beskalan Lanang in Figure 4, for example, is a woman that you will meet again in Chapter 3. A person’s body type as well as their personality and disposition tended to be considered in relation to what dances they were steered towards performing by teachers, mentors, and consumers—that is, what patrons requested or hired them for, among other factors. Individuals were also drawn to certain dances based on affinities they felt for the dance. For example, a dance may resonate with a dancer’s own personality, disposition, and ways of moving. Indeed, performing dances as cross-gender dance in Malang—both women performing male-style dance and men or waria performing female-style dance—was common and for some dances was expected.

Cross-gender performance has had multiple meanings in east Java and related cultural regions. On one end of the spectrum, it has been an accepted practice integral to local worldviews. Traditions of cross-gender performance in masked dance, social dance, and popular theater have existed throughout what is now the province of East Java since at least the 1820s and early twentieth century (Pigeaud, 1938, pp. 277, 301, 321–323, 328). Paul Wolbers (1989; 1993) and R. Anderson Sutton (1993) link boys’ performance of female-style dance for ritual ceremonies in Banyuwangi to centuries-old Hindu and indigenous Javanese imagery in which androgyny represents cosmic power and fertility. There are also historical and contemporary examples of cross-gender performance, both males performing female-style dance and vice versa, in Central Java and West Java (Sunardi, 2015, pp. 20–21). For example, males performed female-style dance in central Javanese contexts, including eighteenth-, nineteenth-, and twentieth-century courts (Raffles, 1988, p. 342; Ponder, 1990, p. 134; Hughes-Freeland, 1995, p. 184; 2006, pp. 65–66; 2008b, pp. 154–157; Sumarsam, 1995, p. 276n59).

On the other end of the spectrum, cross-gender performance has been a strategy that individuals have employed to negotiate official Indonesian constructions of manhood and womanhood. Influenced by Javanese aristocratic, Dutch colonial, and Islamic norms, dominant Indonesian constructions have tended to separate maleness from femaleness, link gender to biological sex in a one-to-one mapping—masculinity to male bodies to man, femininity to female bodies to woman—and privilege heterosexuality, shaping gender ideologies the Indonesian government has promoted since the declaration of independence in 1945 (Blackwood 2005: 866, 869–871; 2007: 185–188; Sunardi 2009; 2013; 2015; 2020; 2022). In a nutshell, dominant, state-promoted constructions of ideal masculinity promoted larger-bodied, physically stronger-looking masculine figures as men were encouraged to assume positions of leadership within the nation as political leaders and lawmakers and within the family as household heads (Shiraishi, 1997, pp. 90–91; Wieringa, 2002, p. 99; Spiller, 2010, p. 26). Women were encouraged to be refined, polite, quiet, and dedicated to the home and their social roles as wives supporting their husbands and as mothers raising their children (Shiraishi, 1997, pp. 90–91; Wieringa, 2002, pp. 99, 130–132; Sunardi, 2009, pp. 462–463; 2015, p. 38).

By embodying the gendered characteristics associated with the opposite sex onstage and/or in their daily lives, males and females in many parts of Indonesia have resisted dominant constructions, as discussed in the work of scholars such as Evelyn Blackwood (2005), Benedict Anderson (1996), Dédé Oetomo (1996), Tom Boellstorff (2004a; 2004b), Jan Mrázek (2005), Herry Gendut Janarto (2005), Setiyono Wahyudi and G.R. Lono Lastoro Simatupang (2005), and Felicia Hughes-Freeland (2008a; 2008b, pp. 161–162). Individuals in Indonesia have contended with multiple logics and meanings of cross-gender performance in different ways in diverse contexts, articulating senses of masculinity and femininity for a variety of reasons. In so doing, as I show in this book about dancers and dance in Malang, performers have contributed to complicated expectations about cross-gender representation. While performers have resisted dominant norms in terms of what type of bodies produce and embody what gender, performers have also reinforced dominant norms, such as norms of behaviors, ways of moving, and ways of sounding that constitute ideal senses of femininity and masculinity.

Similarly, cross-gender performance in various Asian traditions has provided cultural space in and through which performers have navigated, negotiated, challenged, and reaffirmed dominant gender norms and ideologies. A few of these traditions, each with rich and complex histories, include Chinese opera, in which males have performed female roles and vice versa (Rao, 2002, pp. 408, 413, 416; Li, 2003; Lau, 2008, pp. 67, 70, 73), Japanese kabuki theater in which male actors have specialized in female roles (Wade, 2005, pp. 114–115; Isaka, 2016), and the Japanese Takarazuka Revue company in which females have played male roles (Robertson, 1998; Solander, 2023). Indeed, performance is an important site in which to explore the production and negotiation of gender.

A focus on performers and performance offers a critical means to explore and examine ways in which individuals produce and represent complex senses of gender. Onstage, people may take on a persona, express themselves through a performed persona, and/or push at dominant norms in ways that they would not do in offstage daily life. In some cases, transgressing dominant norms is culturally and socially accepted onstage but not in daily life. Transgressing dominant norms onstage has the potential to change ideas about what is socially acceptable in daily life as people become more used to seeing it onstage. Performance can thereby open cultural space for change. Performance also provides a window into the production of gender because performers’ manipulations of their bodies are particularly exposed and conventions of embodying, producing, and representing femininities and masculinities are particularly visible. Performance denaturalizes gender because it makes the reality that gender is a construction and an enactment—rather than inherent—more transparent, a point I draw from Judith Butler’s analysis of drag (1999, p. 175; Sunardi, 2015, pp. 14–15).

I foreground the agency of artists who perform cross-gender dance as individuals who produce complex constructions of gender through performance and play critical social roles that affect local senses of identity. On the one hand, they may reify mainstream cultural norms in Malang by performing ideal constructions of “male” and “female” in terms of physical appearance, behavior, and social position through established dance forms. On the other hand, they may simultaneously undermine a one-to-one mapping of biological sex and gender role. They may further challenge norms through the different personas they embody when performing onstage and when living their daily lives. This is not to say, however, that dancers do not have many reasons for performing cross-gender dance—including earning a living.

My approaches to thinking about gender have been influenced by many scholars, only a few of whom I discuss here. From the gender theorist Judith Butler (1990; 1993; 1999), mentioned above, I have built on the notion of gender performativity—that gender is an unstable cultural construction that is produced by and through what a person does. In other words, a person is not a gender because of the biological sex they were assigned at birth, but because of what a person does to be and identify as a gender, which can change and shift. “Doing” a gender—or performing a gender broadly speaking and not just on a stage in a theatrical sense but also in daily life—may include how a person dresses, acts, speaks, does their hair, wears makeup (or not), and so on. It is important to recognize that a person does and thereby produces their gender in relation to many other facets of their identity, as the theoretical framework of intersectionality emphasizes; such facets that intersect with gender include but are not limited to a person’s ethnicity and/or race, class, age, generation, national identity, regional identity, religion, political affiliation, and so on—categories that, like gender, are also fluid and products of complex webs of power (Crenshaw, 1991; Nash, 2008; Cho, Crenshaw, and McCall, 2013, p. 795; see also Del Negro and Berger, 2004). Cultural and historical context, including the place(s) where people live, work, and spend free time are thus critical in understanding how individuals negotiate gender in particular ways.

Butler’s argument that it is the repetition of cultural norms that makes many people believe that the norms are natural and normal, rather than cultural constructions that people create, has also shaped my thinking (1999, p. 12). The potential for some aspect of the repetition to differ from previous repetitions, however, does allow space for change (1993, p. 234). In other words, adjustments people as active agents make to the way they do a gender in a particular context can lead to changes in what are culturally acceptable (or contested) ways of being—or doing—that gender. Such adjustments and changes may range from subtle to radical. Perhaps you can think of some examples.

An equally influential point that I have taken from Butler’s work is that biological sex, in addition to gender, is culturally constructed (1990, p. 275; 1993, pp. 1–2; 1999, pp. 10–11). That is, the ways people understand biological sex, what comprises biological sex, how many sexes exist, and so on, are culturally constructed. Butler’s work has helped me to formulate ideas about how gender and biological sex are performed, articulated, created, and negotiated by artists in Malang both onstage as performers and offstage as they live their lives. Artists thereby impact and create or produce culture at large. Another way to put this is that artists contribute to cultural production, including the cultural production of gender. Butler and others also importantly acknowledge that while cross-gender performance can challenge what types of bodies can embody, represent, and produce which genders, cross-gender performance can also reinforce dominant norms, as I have mentioned earlier. For example, a person assigned male at birth performing hyper-femininity on stage as a drag artist may reinforce dominant social pressures for how women should look, sound, and act (Peacock, 1987, pp. 168–172; Butler, 1993, pp. 125, 231, 237; Anderson, 1996; Shaw, 2005, p. 16).

The gender studies scholar Judith Halberstam (now Jack Halberstam) and the anthropologist Tom Boellstorff have provided approaches and vocabulary to identify and analyze complex senses of gender in Malang. Halberstam has offered the concept of female masculinity—senses of masculinity that are produced, owned, and embodied by female bodies and differ from male masculinities (1998, pp. 1–2, 15; Blackwood and Wieringa, 2007, pp. 9, 14–15; Blackwood, 2010, p. 29; Sunardi, 2013, p. 141; 2015, p. 11; 2022, p. 290). From Tom Boellstorff I have taken an analogous concept of male femininity—senses of femininity produced, owned, and embodied by male bodies (2004b; 2005b, pp. 169, 171, 175; 2007, pp. 82, 99, 108; Sunardi, 2013, p. 141; 2015, p. 11; 2022, p. 290).

A male–female gender binary or spectrum in many ways is still assumed or maintained through terms such as female masculinity and male femininity (Sunardi, 2015, pp. 10–11). In the cultural context of Malang (and Indonesia more broadly speaking), that binary is strong and, in addition to female masculinity and male femininity, the concepts of “male” and “female”, “man” and “woman”, “masculinity” and “femininity” have been useful, as Boellstorff highlights for Southeast Asia in general (2007, p. 208). At the same time there is also gender fluidity as people move between different ways of doing gender, and gender pluralism, which the anthropologist Michael Peletz explains:

includes pluralistic sensibilities and dispositions regarding bodily practices (adornment, attire, mannerisms) and embodied desires, as well as social roles, sexual relationships, and ways of being that bear on or are otherwise linked with local conceptions of femininity, masculinity, androgyny, etc. (2006, p. 310)

Gender fluidity and gender pluralism are two additional interrelated themes that thread this book.

Complicating the gender binary in Indonesia is the waria gender identity or category. I recognize that using English terms for waria presents challenges, as discussed by Tom Boellstorff. For example, since the waria he consulted “usually see themselves as originating from the category ‘man’ and as remaining men in some fashion”, he found that the terms transgender and transsexual fell short in capturing how they understood themselves (2007, p. 82). Additional challenges of using English terms include the continuous emergence of new vocabulary in transgender studies, the array of terms transgender people use to identify themselves in English-speaking contexts such as the United States, and differing attitudes among transgender people about the same terms; what one person may find respectable another may find insulting (Green, Denny, and Cromwell, 2018, pp. 100, 106). Terminology also changes in Indonesia. More recently, in 2014 and 2015, Benjamin Hegarty found that waria understand the English word transgender and that some use it in Yogyakarta and Jakarta, places frequented by foreign researchers and journalists who may have contributed to its usage (2017, pp. 78–79).

The gloss that I use for waria—males who dress and live as female—is meant to communicate the male femininity that is a key part of waria identity for many and to allow for the recognition of waria as a gender category that is distinct from that of “woman” (Oetomo, 2000, p. 50; Boellstorff 2004b; 2005b; 2007; Sunardi, 2015, pp. 63–93). At the same time, I do not mean to imply that there is any one way of living as female or identifying as a woman, that all males who live as female necessarily identify as waria rather than as women, or that identifying as a waria and as a woman is mutually exclusive. Hegarty analyzes an interview with a group of waria in which one, for example, does refer to herself as a woman (2017, p. 86; Sunardi, 2022, pp. 296–297).

Evelyn Blackwood’s and others’ writing about the enactment of gender being dependent on context has also influenced my analytical approach—that is, that people may do gender in different ways in different situations—and I extend Blackwood’s concept of “contingent masculinity” to think through instances of contingent male femininity, contingent female masculinity, and the contingency of gender more broadly speaking (2010, p. 21; Oetomo, 2000, p. 50; Boellstorff, 2007, p. 100, Sunardi, 2013, p. 141; 2015, p. 11). For example, a person may express gender in one way when at home with their family and in another when out with friends. A person may do a gender in a particular way when they are performing onstage and in another when they are living their daily lives. Onstage–offstage negotiations of gender are a fourth theme of this book.

My research methodology is grounded in my training in ethnomusicology, a discipline that centers the relationships between culture and music and related performing arts such as dance and theater. As in anthropology, a discipline that has strongly influenced ethnomusicology, one important research methodology many scholars employ is ethnographic fieldwork, and specifically participant observation—spending time with a group of people (however defined) to learn from them by listening to what they have to say, observing what they do, and participating in activities with them, such as playing music or dancing. Although I focus on dance in this book, I believe it worth including that given my interest in both music and dance performance practice, I spent much of my time in Malang studying the playing techniques of several gamelan instruments, focusing on Malangan and east Javanese playing styles as well as studying east Javanese male- and female-style dances. I had two or more private lessons most weeks—each of which tended to be at least two hours in duration. In between lessons I practiced extensively alone, with a friend, or with groups of various sizes. Sometimes I joined practice sessions of other groups, and sometimes I organized practice sessions with the musicians in my primary gamelan teacher’s group so that I could gain more experience playing or dancing with a fuller ensemble. With the help of my teachers, I also organized video and audio recording sessions to document the music and dance that my teachers were teaching me.

Lessons, practice sessions, and recording sessions provided not only invaluable experience in learning about how the music and dance forms worked, but also provided many opportunities for me to listen—and here I emphasize listen, and the intentionality of listening—to musicians and dancers as they shared their experiences as artists, their perspectives about the arts, their offstage lives, and more. I also conducted formal interviews with artists. Hanging out with my teachers and other artists provided additional rich opportunities to listen. I listened to people in the community in which I resided, including neighbors and people who became friends. Chit-chat with taxi drivers and mini-bus drivers were further opportunities to listen and to learn. My fieldwork included attending performances—where I was often provided explanations and commentary from my teachers, mentors, other artists, and members of the audience. Sometimes I recorded performances and watched them with my teachers. Watching performances together—either live or videotaped—gave me many opportunities to learn more from my teachers as they explained conventions, identified musical compositions, identified what performers were doing well and what they thought was not going so well or what they thought performers were not doing right. In this book I use the phrase “personal communication” in the in-text citations to indicate information I learned from listening to people in all of these ways.

I was also generously given opportunities to perform as a musician and dancer. These experiences taught me more about the arts, allowing me to experience the rush of performance in my own body, and provided opportunities for me to continue learning from my teachers as they offered advice for how to improve. Audiences received my performances very generously, encouraging me enthusiastically; many seemed appreciative that I would come all the way from the United States to learn about local traditions in Malang. For many, I believe, it was enjoyable to watch a foreign person perform local arts for the unusual aspect of it, and because on some level it showed that a Western person—and a US American in particular—was not as good as a local performer, which showed that Western culture and people were not inherently superior to Javanese/Indonesian people, in effect disrupting assumptions of Western superiority that have been internalized as a psychological impact of colonialism (Williams, 2001, p. 13; Sunardi, 2015, pp. xxiv–xxv; 2023, pp. 6–7).

While ethnographic research is the heart of my research methodology, I recognize that biases, implicit and explicit, are part and parcel of humans working together. For example, most of the artists I consulted over the course of my research in Malang were men as the professional traditional performing arts scene was largely male dominated. I have attempted to balance, at least somewhat, men’s perspectives, voices, and experiences with those of women and waria I consulted, as well as my own perspectives as a woman (Sunardi, 2015, p. xxii). I also recognize that each individual—including me—has their own biases, opinions, perspectives, and so on that are shaped by multiple factors such as life experiences, personality, positionality, moment at which we interacted and what we were thinking about and feeling at that moment, and so on (Sunardi, 2015, p. xix). To present a range of perspectives and experiences, I offer portraits of six individual artists in this book, most of whom I consulted multiple times over the course of my fieldwork to build trust and to listen further, or in the case of a deceased artist, one I heard about on multiple occasions. And I strongly encourage you to read other analysts’ work on Java, Indonesia, gender, other topics I address in this book, and other interests this book may spark to engage with still more perspectives, as my positionality (and personality) as a researcher also impacted my findings and the work that has resulted, including this book.

My own identity and perceptions of my identity were certainly factors as I worked with individuals in Malang, as were complicated power dynamics. I worked with a number of teachers as their student—they were the masters of the tradition and I was a novice. I was at their mercy in terms of what they chose to share (and not share) depending on what they felt I was ready to learn, what they wanted me to know to take back to the United States, what they felt was appropriate for me to know, and what they were thinking about on any given lesson day. At the same time, my status as a foreign researcher from the United States—I was in a PhD program during my fieldwork spanning 2005–2007 and on subsequent visits was a professor at a US university—held a lot of clout for many of the people with whom I worked. Given that I am a mixed-raced (Black, white, and a little Native American), brown-skinned woman married to a Javanese man, my skin color and marriage inclined people to think that I was like them to some degree. Many held their arms next to mine, noting the similarity in skin color, and saying things like “we are the same”. Many assumed that I sincerely loved Javanese culture because I had married a Javanese person. Some expressed that I could understand them because I was from a historically marginalized group in the US as a Black/Brown person—that is, I could understand their plight as marginalized people in Indonesia due to their education level, class level, and/or regional identity as east Javanese culture is generally seen as less prestigious than central Javanese culture.

The maleness and femaleness many people in the community perceived in me due to my height and broad shoulders also led me to be mistaken for a waria. My activity performing a female-style dance that was associated with waria performers and the hellos I said to waria performers I saw on- and offstage reinforced assumptions that I was a waria, too. This gave me insights into how waria are perceived and treated, topics I discuss in the next chapter. (For more on my positionality as a “tall-broad-shouldered-foreign-but-brown female researcher”, see Sunardi, 2015, pp. xxiii–xxix).

One question that I am often asked is how I came to be interested in Javanese culture in the first place. In some ways, the answer is quite simple—I became entranced by the sound of gamelan music during a music of Asia survey course I took as an undergraduate at the University of California, San Diego. It was unlike anything I had heard before and it captivated me. I had loved taking piano lessons as a child, playing clarinet in school concert and marching bands, later switching to mallets in marching band, and playing various saxophones in jazz band. Playing mallets led to an interest in percussion that I pursued in college and contributed to my fascination with gamelan—an orchestra comprised largely of percussion instruments. Right around the time I fell for gamelan, I was finalizing where to study abroad during my junior year (which I had long wanted to do) and decided to apply to the University of California study abroad program in Indonesia, which was based in Yogyakarta. I was accepted and during that program, 1997–1998, I had the opportunity to study gamelan and a little dance. I also met the man who would become my husband. The program was ended a little earlier than planned in May 1998 rather than July 1998 due to the political unrest surrounding the end of the authoritarian Suharto regime. After the political situation became more stable, I returned many times to visit my boyfriend, later fiancé, continuing to study gamelan and deepening my studies of central Javanese dance, particularly female-style dance. Aside from brief forays into ballet and tap as a child, I had not pursued much dance, preferring sports. With my boisterous, chatty, heart-on-my-sleeve demeanor, it was a new challenge to focus on central Javanese female-style dance with its controlled, subtle, and graceful movement and calm, unchanging, mask-like facial expression.

Fast forward to 2003, when I was in a PhD program in ethnomusicology at the University of California, Berkeley, I saw the internationally renowned master central Javanese dancer Didik Nini Thowok (b. 1954, Didik Hadiprayitno) perform Beskalan Putri , a female-style dance from Malang, in San Francisco (Sunardi, 2015, p. xxii). Didik, a celebrity in Indonesia, is a man who specializes in female-style dances (Janarto, 2005; Mrázek, 2005; Ross, 2005; Hughes-Freeland, 2008a). I had had the opportunity to meet him when I was living in central Java, and had the opportunity to participate as a musician in a performance project he directed that featured males, including him, performing female-style dance. (I decided to get into the cross-gender aspect and dressed as a male musician for the performance.) When I saw Didik perform Beskalan Putri in San Francisco, I was again taken—like when I was an undergraduate student and heard gamelan music for the first time. I had found my dissertation topic—or at least one of the dances that would be at the center of my dissertation research—and I plunged into the issue of gender.

During a preliminary trip to Malang in 2004, Didik helped introduce me to the community that became the base for my fieldwork. Once there, I learned about other east Javanese dances, including Ngremo and masked dances, and about east Javanese gamelan music and theater forms. In some ways, my previous studies of central Javanese gamelan and dance gave me a little bit of a head start on studying east Javanese gamelan and dance, but it also led to some mistaken assumptions about east Javanese music that I had to unlearn, as well as a certain touch in my playing and dancing that performers identified as central Javanese (Sunardi, 2010, pp. 99, 106, 118–119; 2017, pp. 62–63). I believe this contributed to my many conversations with performers about what made the music and dance I was studying east Javanese and Malangan in particular, which, as indicated, was critically important to them. My own interest in gender and performers’ attention to the articulation of local identity through the arts has thus been at the center of much of my work in various manifestations, including this book.

This chapter has offered an introduction to Fashioning Femininities, Making Masculinities: Gender, Performance, and Lived Experience in Java, Indonesia , including its focus on gender as a cultural construction that people continuously negotiate and ways we can understand how individuals negotiate gender through the performing arts and their lived experiences as artists in specific cultural contexts—in this case Malang in east Java. I have presented my analytical approaches to gender, including gender performativity—gender as an unstable cultural construct that people produce by “doing” gender in particular ways (Butler 1990; 1993; 1999)—and intersectionality—gender intersects with many other aspects of a person’s identity, all of which are fluid and produced in and through complex webs of power (Crenshaw, 1991; Nash, 2008; Cho, Crenshaw, and McCall, 2013, p. 795; see also Del Negro and Berger, 2004). I also build upon the concepts of gender pluralism (Peletz, 2006), female masculinity (Halberstam, 1998), male femininity (Boellstorff, 2004b; 2005b; 2007), and contingent gender (Blackwood, 2010).

My intent in this chapter has also been to make transparent that this book and its findings are products of my individual experiences and perspectives as a researcher and very much situated in my experiences conducting ethnographic fieldwork in Malang primarily spanning 2005 to 2007, with a prior visit to Malang in 2004 and subsequent visits, the most recent of which was in 2015 at the time of this writing. No less influential in the shaping of my work is my positionality as a mixed-race US American woman researcher, including my path to Java and east Javanese performing arts. I invite you to take this book for what it is and to seek out other perspectives. I am nonetheless excited to introduce you to individual dancers in the following two chapters. Through the stories they shared about their lives and experiences, as well as the perspectives they shared about the arts, we have the opportunity and privilege to explore themes of onstage–offstage gender negotiations, gender fluidity, gender pluralism, and spirituality.

My hope is that by the time you finish this book, you will be able to:

1. Identify ways the performance of dance in Malang provides cultural space in which gender norms can be reinforced, subverted, challenged, navigated, and so on—sometimes all at the same time;

2. Provide examples of complex senses of gender that both push at and reinforce a culturally dominant heterosexual, male–female gender binary;

3. Explain how the cultural context of Malang informs individuals’ negotiations of gender in the performing arts on- and offstage;

4. Apply theoretical and methodological approaches used in this book to the exploration of gender and performing arts traditions in various cultural and historical contexts; and

5. Build from the theoretical and methodological approaches used in this book to develop new approaches that are informed by the performing tradition(s) and cultural context(s) you are analyzing.