DOI: 10.3726/9781916985285.003.0002

In this chapter, William presents information regarding the circumstances leading to becoming a refugee. The chapter starts with a depiction of his early days in his home village prior to the onset of the Second Sudanese Civil War. He then transitions into the narrative of the outbreak of war in his village, its consequential impact, the remarkable acts of sacrifice he observed among ordinary individuals amid adversity, and the living conditions within the refugee camps.

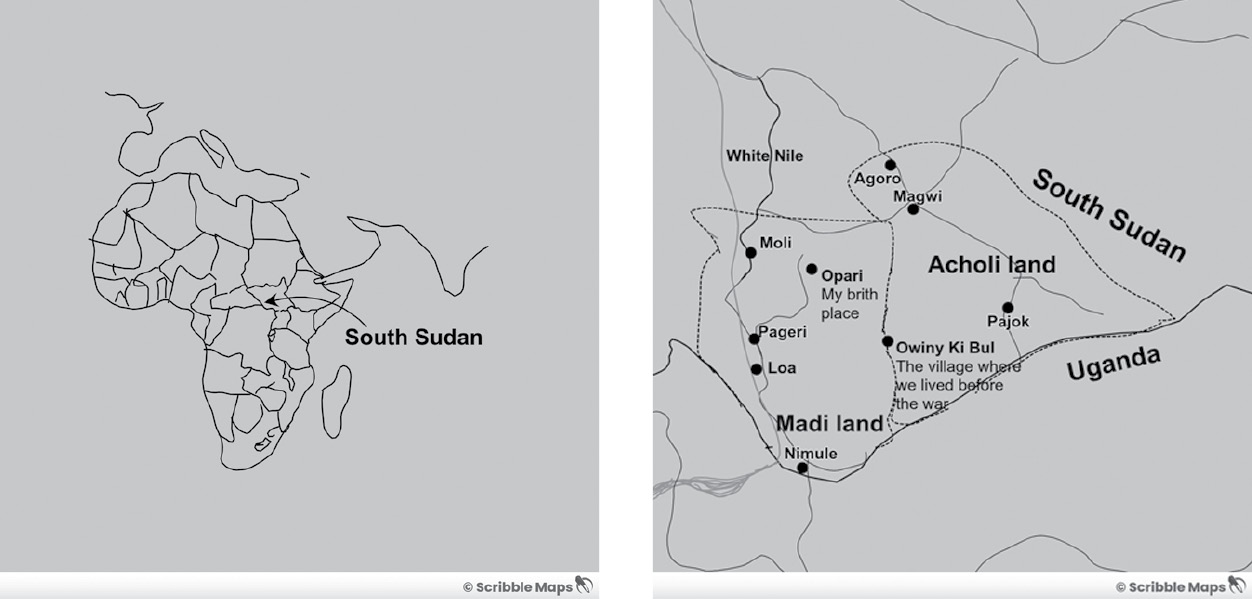

I was born in what was then called Sudan, now South Sudan – specifically, in Ma’di land, in Opari. We lived in a village on the border between Ma’di and Acholi land, called Owiny-Kibul, near the now South Sudan and Uganda border (see Figure 1). I had five other siblings, so there were eight of us in total, including my parents. During the farming season, we lived on the farm outside the main local township of Owiny-Kibul where my father had a quarter, and during the dry season, we lived in the main local township. Although many people in this village commonly spoke Acholi, they also spoke Ma’di. Nonetheless, the village was peaceful, and most people were happily involved in subsistence farming, and small-scale animal husbandry, including my parents.

As a farming community, people had enough food throughout the year to feed their families and give some away to help the widows and orphans in the village. Every home had granaries to store their family’s food, keeping it dry and safe from termites. People had all sorts of foods to sustain themselves – groundnuts, maize, cassava, peas, sesame, sorghum, sweet potatoes, and many more. People in the village also reared goats and sheep, which were tended to by young boys. We had a river that flowed all year round which we used for drinking water and fishing.

Our small village had a unique way of life that was different from what I am accustomed to today. Rather than buying food from the markets as I do now,, we had a self-sustaining system. We produced everything we needed to survive, from vegetables and grains, to livestock and poultry. Our community had a deep connection to nature, and we took pride in our ability to live off the land.

Despite our self-sufficiency, there were a few essential items that we had to buy from the market – soap and salt being the most important, as they were not something we could produce ourselves, so we relied on Ugandan merchants to bring these goods to our village. Occasionally, second-hand clothing and shoes were also sold, but they were not a necessity, except during Christmas when people bought new clothing and shoes for themselves. As most people didn’t have hard currency, most of the exchanges of goods and services in the village were in the form of barter trade – people directly exchanged goods for other goods or services, for example, exchanging ten kilograms of grains for a bar of soap.

Geographic position of my village (Source: Google Maps)

Our village’s unique way of life was not without its challenges, but we took pride in our self-sufficiency and our ability to produce everything we needed to survive. We were a close-knit community who worked together to overcome any difficulties that came our way. For example, people made their own soap from shea nut or sesame oil when the Ugandan merchants were unable to bring goods to our village. We crystallised salt from patches of salty soils and ashes from specific trees. This process was time-consuming and required a lot of effort, but we did it when necessary.

In the village, everyone had a designated responsibilities. The parents were responsible for working and providing food for their families. Young boys who were not yet able to perform heavy tasks, such as cultivating, were given the duty of looking after the animals. The younger boys and girls were either required to accompany their parents to the garden or to stay at home and take care of the babies. I happened to fall into the latter category and was responsible for babysitting my younger sibling while my mother was busy with her work. Fathers showed their sons how to build houses, make arrows, bows, and spears, hunt, till the land to feed their families, and help find good girls to marry. Fathers were also responsible for paying a dowry when their sons got married. In our village, people rarely used their goats and sheep for meat; instead, the animals were primarily reserved for use as dowry payment by the family of a boy seeking marriage.

Every morning, young boys would take their goats and sheep to the pastures by the riverbank and spend the day in the bush, caring for their animals. As a result, I started rearing goats at the age of six. I used to wake up early and follow the older boys who were driving goats and sheep to the pastures. Upon reaching the pastures by the riverside, the older boys would engage in wrestling, and various other activities, including swimming, hunting, and fishing. However, as younger boys, we were not allowed to engage in any of these activities. Instead, the older boys made us look after the animals while they grazed by the river. As we got more opportunities to go goat-rearing as young boys aged around six to seven years, we became confident and began competing with some of the older boys. We competed in many things, ranging from running, target shooting with bows and arrows, distance shooting, and many other things that young boys do. We also shot fish with bows and arrows from the river.

In our village, gender roles were clearly defined as they had been for generations. Boys were mentored by their fathers to fulfil their roles as providers and caretakers of the land, while girls were guided by their mothers to prepare them for their future roles as nurturing and caring mothers. We all learned together. This intergenerational transmission of societal roles and responsibilities was integral to the fabric of our community. We engaged in the collection of firewood during the day to facilitate the creation of an evening fire, mirroring the practices of our forebears. Each evening, we gathered around the fire, where our elders regaled us with stories about the stars and the fundamental questions of existence. As young individuals, we were recipients of narratives that had been transmitted across generations. Within our cultural milieu, the mode of knowledge preservation centred on oral tradition and musical expression, rather than script-based mediums. Our ambitions focused on maturing into individuals who would perpetuate our traditional lifestyle, characterised by its perceived purity, unadulterated nature, and inherent virtue.

People from different tribes lived together, including non-Sudanese people who had been in our village for generations, such as families of Greek origin, Middle Eastern heritage, and Ugandans. Our people were kind-hearted and shared land for cultivation. There were intermarriages among the different tribes, and people respected each another’s beliefs and practices, irrespective of religion. Women were held in high regard and seen as the foundation of the family. Our village was secular, and our people did not discriminate against others based on their tribes, gender, race, or beliefs. We had rainmakers and fortune tellers, who were allowed to practice their ways of life, provided they did not intend to harm anyone. Fortune tellers gave people amulets made of cowry shells to protect against bad spirits. Rainmakers had a special status in the village because they had been used for generations to forecast rainfalls.

Our village market opened only on Saturdays in the afternoon after people returned from working in their gardens. At the market, women sold traditional beer known as kwete or malwa, and distilled alcohol. The market was a popular spot for people to catch up with one other and to meet people from other nearby villages. Market day was also popular for courting among the single, mature-aged boys and girls in our village. Courting a girl was a competitive affair, with different groups of boys often vying for a girl’s attention. Girls could date as many boys at a time as they wished, and would eventually choose one to marry.

Courting could last for several months, or even years, with several boys coming to the girl’s home to get to know her better. When a boy came to the home, he would stop at the edge of the compound and wait for the girl to welcome him inside. Sometimes, the girl would ignore the boy, and he could wait for three or four hours before being seated. Sometimes, the girl’s mother would provide the boys with water as they waited for a welcome from their daughter. These were the activities that we looked forward to when we came of age, but war robbed us of that life.

In the early days of 1986, the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) made an unexpected appearance in Owiny-Kibul, a village devoid of any Sudanese Government presence. We did not have any police or government administration in the area. Despite the absence of conflict, the SPLA insisted that the residents leave the area immediately. As it was farming season, my father had already moved us to live on the farm. On that day, as I sat in our house on the farm, people – including children and the elderly – started pouring into our home with luggage on their heads and water jerrycans in their hands. I was six years old at the time.

I was surprised by the influx of people into our home, and I wanted to find out what was happening. I turned to my mother and asked, “Mama, a Ma’di word for ‘mother’, why are people gathering in our home?” But my mother did not respond. The number of people congregating in our home continued to increase. There were people under all the tree shade in our compound, granaries, and veranda. We had a goat pen at the edge of our compound, and those people who could not find shade occupied the goat pen. I was uneasy with strangers filling all the available shades in our home. I again sought information from my mother, but again, she did not respond. That afternoon, my “Baba”, a Ma’di word for “dad”, was not home. He had gone hunting. “Has something happened to Baba?” I asked myself quietly. I left my mother, who was panting heavily and headed towards my grandmother’s place. When I reached there, my grandmother interrupted me before I could ask her anything. She instructed me to wake up my uncle, who was sleeping under the veranda. Despite the noise around us, my uncle continued to sleep soundly, which surprised me.

In our village, there is a procedure for waking people from their sleep. To wake someone, you must say their name and then gently touch them. If you do this three times and the person does not wake up, you leave them to continue sleeping. However, if the matter is urgent, after three attempts to wake the person up, you shake them vigorously and call their name louder until they wake up. When my grandmother asked me to wake up my uncle, I called his name and touched him three times, but he did not wake up. I returned to my grandmother and said that my uncle must be feeling exhausted. I suggested that we should allow him to complete his sleep. However, she insisted that I should shake him vigorously until he woke up. I went back and woke my uncle up by nudging him vigorously.

As I shook my uncle awake, I noticed an uneasy look on his face. A small stream of fresh saliva flowed down his cheek, and his eyes were bloodshot and tired. His legs were covered in dirt, forming rough, scaly clay stockings, and his shirt was soaked with sweat, leaving cloudy patterns throughout. The collar was darkened with thick sweat and dirt, which weighing heavily on his shoulders. When my uncle woke up, he looked around the crowded room as if he was lost for a moment. “Dada says I should wake you up”, I informed him. “Dada” is a Ma’di word for grandmother. My uncle didn’t say anything to me but sat there with his hands wrapped around his knees, looking confused too. He suddenly got up and headed to my grandmother.

As soon as my uncle walked away to see my grandmother, I caught sight of my father returning from his hunting trip that afternoon. However, shortly before he entered the compound, a loud noise rang out. People who were sitting under the shades quickly dispersed and started running. My mother shouted at me to run as well, but I was confused and didn’t know what was going on. I thought the sound was coming from a bridge in the village that was built by the British during their governance of the Sudan (see Figure 2). As children, we crossed the bridge frequently. However, because the bridge was built using steel with certain sections in a state of disrepair, it made a lot of loud noise that echoed the loud sound that rang out. As a result, when I saw people start running away, I was confused, and I asked why they were running from the sound of the bridge.

The bridge in our village built by the British in about early 1900s. (Source Google Image: Photo by Luo Prince in December 2021)

I saw my grandmother run with all her might, holding her walking stick in her right hand, while her left hand supported her hips. My father dropped the bushmeat that he had hunted, and immediately grabbed my younger sister, making me realise that something was wrong. I followed the others and started running as fast as I could. When we used to herd goats, we were taught to recite a particular song in our minds and run without looking back whenever being chased by wild animals. The song we sang literally translates to: “the backs of my head watch over me, my face is not watching me”. Metaphorically, this song is intended to invoke a sense of feeling unwatched and vulnerable, while also conveying the sentiment that those expected to look out for you are unable to do so. I sang that song in my mind, repeating the same line again and again. When I stopped, my knees shook, and I was all alone. My heart was racing and beating hard in my chest. I did not know where I was, or how I had become separated from the rest of the people. After a while, I started seeing other people coming past, and walking deeper into the bush. I waited for my parents until they arrived, and joined them to walk deeper into the bush.

Since that day, we experienced a constant disruption. Despite the efforts of everyone, the danger of war was still present and eventually caught up with us, causing great harm to our people. Armed militias, mainly from Parajok, Magwi, and Polataka, which were supported by the government, raided our hiding places frequently because they assumed that the people in our village supported the SPLA, forcing us to move constantly. We were defenceless, and the people in our village did not have any weapons to protect themselves. In our village, there were three men, including my father, who possessed arms with limited ammunition. They used their ammunition sparingly, reserving it for exceptional circumstances, such as strategically diverting attacking militias away from our hideouts. Despite their efforts, there were instances when our hideouts were burnt down, children were kidnapped, and animal stocks were taken during raids.

Unfortunately, these raids became a constant event that would define the lives of people in our village for decades to come. My grandmother and uncle decided to return to Ma’di land, which was relatively peaceful then. Due to the losses experienced, many people fled to refugee camps in Uganda in 1989, where they remain today, but my family, and a handful of families stayed back. I was not sure why my father decided to stay despite the risk to our family. There were numerous instances when local militias attacked our hiding places because of supporting the SPLA, sparking fear among the children in our village, including myself. It was a constant state of apprehension and uncertainty about when the next attack would occur. On one occasion, I became disoriented in the bush for several days during an attack, leading my parents to believe I had perished or been taken captive. Fortunately, I accidentally stumbled upon a neighbouring village, whose inhabitants assisted me in returning to our village.

The war situation in our village was evolving quickly. Soon, men who remained in our village started to join the SPLA, including my father, to protect the village against militia attacks. Women watched their men vanish on the horizon as if they were just going for a short stroll, some without letting their wives/mothers know. That was the last time some of them would see their beloved husbands or sons. As children, we would ask our mothers about our fathers, but not a single mother answered. The only time we knew where the men had been was when some of them returned to the village, armed, after several months of being away from home.

My father, as I would later learn, never wanted to join the SPLA rebels. However, the relentless attacks on our hideouts, and the torture that was perpetrated by the returning SPLA soldiers forced my father to make the fateful decision to join the SPLA. Just like that, the war took my father away from me. Every evening, we waited with our eyes on the road, hoping that he would come home, but he never did. We held onto hope, but it was false. The dreaded fate we feared most came to pass. Our mother received information from the returning SPLA soldiers that our father was killed in a battle somewhere at the Sudan-Ethiopian border. I was about eight years old at the time.

In our traditional society, the absence of a father figure can pose significant challenges for young boys, as paternal guidance plays a pivotal role in their development and mentorship. Similarly, the absence of a mother can have a similar impact on the lives of young girls. Personally, I found myself in a difficult situation and faced several challenges due to the death of my father. During that period, I found myself having to make independent choices and decisions. I observed and absorbed valuable insights by listening to the advice that fathers gave their children, and I thoughtfully considered how this wisdom could apply to my own life. Additionally, I observed fathers imparting practical skills to their sons, such as the construction of makeshift houses, and other traditional male roles within our society. I undertook tasks that were typically reserved for older boys, such as cutting poles and erecting temporary shelters. Moreover, I took on the responsibility of looking after my father’s goats, until they were gradually consumed by the SPLA.

Following the news of my father’s passing, my mother would wake me and my two older siblings – an elder sister and a brother whom I followed – at 4:00 a.m. to go to the garden. During the planting season, the grasses were tall and heavily laden with the early morning dew. By the time we reached the garden, we were drenched, cold, and shivering. However, when the sun rose, we gradually became dry and warm once again. We did not have breakfast, but we had water to drink. Our collective effort for the day was worth our father’s daily work. On our return from the garden, our mother would proceed to the riverbank to distil alcohol. Some men would commission specific quantities of alcohol and reimburse her through labour in our garden. On some occasions, my mother enlisted a group of men to work in our garden in exchange for “kwete”. Consequently, despite my father being deceased, we did not experience frequent famine because of our mother’s efforts.

However, because of the constant attacks on our hideouts by the riverbank, I got lost again in the bush. In the absence of my father, my mother encountered considerable difficulties, eventually leading to a collective effort by village inhabitants to locate and retrieve me following a three-day search. But in late 1990, when I was ten years old, I was wounded on my right leg in one of the attacks on our hideouts by the riverbank and taken captive. In captivity, I experienced challenging and traumatic experiences, including physical and psychological abuse, deprivation of basic needs such as proper medical treatment for my wound, food, water, and confinement in a small room.

These experiences have had an impact on my psychological and emotional well-being. During and after my captivity, I started having some strange dreams that I never had before. In one of the dreams, I was being chased, but I was unsure why people were after me or what I had done to be in such a situation. Whenever people came to chase me, I would spread my wings and fly away from them. Flying like a human bird high up in the sky, away from trouble, felt amazing. However, whenever I landed by a riverbank, people found me, and I had to fly away again. In 1991, I escaped captivity, fled to my maternal grandmother in Ma’di land, and became completely separated from the rest of my immediate family. Consumed by war, I never saw them again. I continued to have this dream regularly, even when I was in a refugee camp in Uganda and Kenya until I went to Canada when I was 21 years old. I will return to discuss my experience in Uganda, Kenya, and Canada later.

Nevertheless, I lived with my grandmother for over a year after I escaped from captivity until the war uprooted us in 1992. During my time with my grandmother, she enrolled me in a school for unaccompanied children, although for a brief period (I will discuss this further in Chapter 3).

I witnessed incredible acts of sacrifice after my grandmother’s township was attacked. It was not just the soldiers who made sacrifices but also ordinary people who performed extraordinary deeds. One particular event stands out in my memory – the day we fled my grandmother’s township. It was an early morning, the grass still wet with dew and the air chilly. I woke up earlier than usual, feeling something was not quite right. I asked my grandmother if I could fetch some water, but she refused, saying it was still too early, and the sun had not yet risen.

I went back to the house that I shared with many other children. I still felt unsettled, so I came out and began sweeping our compound. After finishing the sweeping, I gathered all the rubbish and set it on fire. When the other kids saw the fire, they came out and joined me by the fire site. Suddenly, I noticed an unusual movement of people along the main road. I alerted the other kids, and we all crouched to the ground to avoid being seen. We instinctively concluded that the township was being invaded and was going to be attacked. We scattered, and each one of us ran into the house where our parents or guardians were sleeping.

I ran to my grandmother and woke her again. I told her about an unusual movement of people that looked like an attack on the township. This reminded her of a rumour she had heard earlier from one of the mothers about an imminent attack on the township. As she peeped outside carefully, she heard footsteps that sounded like military boots. Quickly, she recoiled her head and signalled me to keep quiet. As it began to drizzle, my grandmother looked outside once more but saw nothing. It was eerily quiet, as though the entire township was deserted. Fear began to overwhelm me, and I felt terrible that I could not run away. In the past, whenever things got scary, I would always run away. But this time was different. My grandmother blocked the door and told me to stay quiet as I hid under the bed. Even from my hiding spot, I was restless and anxious. All I wanted was to escape far away from the war that threatened to consume us.

A gunfight broke out 30 minutes after it started drizzling. I was not sure why it took so long for the fighting to start this time. Suddenly, the township was filled with the sound of crackling gunshots. The battle lasted for two to three hours before the township was finally taken over, and the SPLA soldiers retreated. As a result, many civilians left the area and fled to the next township.

The next township was about three-days walk. There were many children and women with loads on their heads walking in groups towards the next township. Some individuals appeared to be tired and had fallen behind, walking at their own pace. Likewise, the elderly men and women were walking slowly but steadily, making sure to keep up with the weaker members of the group. They all held tightly onto their walking sticks to support their weight and alleviate some of the stress on their bodies. The elderly women used long walking sticks in their right hands and supported their waists with their left hands, while the elderly men had shorter sticks. As the group was walking, a rebel commander drove past them in a military jeep on his way to the next township.

As we were travelling away from the town we had escaped, my grandmother suddenly realised that she had left behind the family heirloom which had been passed down through generations. Despite the distance, she decided to go back and retrieve the item. The family heirloom was a symbol of social status and was traditionally inherited by the firstborn, regardless of their gender. My grandmother said she could not continue the journey with us without the family heirloom. Before she went back, she asked me to wait for her under a big tree where most people passed and rested. She instructed me not to go anywhere or follow anybody. She was the only person close to me in my bloodline, and I was living with her at that time. I nodded, and off she went.

I was waiting for my grandmother, and my eyes were constantly directed towards the path, eagerly anticipating her arrival. The six hours I spent under the tree felt like an entire week without any sleep. Gradually, most people left, and only a few arrived, and most of them looked very weak. Two hours after my grandmother had left, I saw a wounded SPLA soldier being carried on a donkey with two other soldiers beside him. I was all alone, and fear gripped me. My one heart was urging me to run away while the other was saying to wait for my grandmother. I made up my mind to wait for my grandmother and not leave her behind. As the SPLA soldiers approached, I stayed put and remained calm.

As they approached the tree, the two soldiers assisted the wounded soldier to the ground. I observed him clenching his teeth in agony. He had been injured in his leg and was struggling to remain upright. He was gasping for breath, exhausted, and perspiring. The weather was starting to heat up. When they requested water, I provided them with some. Water was an incredibly important and valuable resource. People always stored water in containers that could be easily retrieved in case of any unexpected attacks. One hour after the wounded soldier arrived, I spotted a family in the distance. As they approached, I noticed a woman with a child strapped to her back and two young children walking in front of her. All of them were limping and struggling to move forward. The woman carried a small piece of luggage on her head, wrapped in a cover sheet. I assumed they were exhausted and looking forward to reaching the big tree for some rest. However, I was confused as to why they appeared so tired after only walking for three hours.

As soon as the wounded soldier saw the woman and her children seeking shelter under the tree, he quickly hopped on one leg to help them. He carried one of the youngest children and placed him under the tree before going to the woman to help her with her luggage. From his pocket, he drew thick biscuits and gave one to each of the two children. The wounded soldier didn’t say a word to the woman or her children, but the woman greatly appreciated his kindness. I was so moved by his speed to react and assist the woman. Humanity is alive, I thought to myself. When the woman and her children asked for water, I gave them what little I had, but we all realised that we were running low.

After resting for another two hours, the wounded soldier instructed the two soldiers to assist the woman to reach safety. He asked them to load the woman’s luggage and the children onto the donkey, and take them to the next town. I overheard him telling the other soldiers that he would be fine, as he was used to such situations, but that it was not the same for the children. The woman was very grateful and seemed relieved. She spoke of how exhausted she and her children were, having walked for seven days from a distant town that they faced hunger. She mentioned that as soon as they arrived in our township, it came under attack, and they had not eat for two days. The man comforted her, saying, “It’s okay. You’ll be fine. Keep going and you’ll find food for the children. Everything will be alright.”

The wounded soldier asked me to go with the woman and her children, but I declined, stating that I was waiting for my grandmother. However, he insisted on staying with me until my grandmother arrived, calling me “Jesh Ahmer”, a Juba Arabic term meaning “Red Army”, which the SPLA often used for unaccompanied minors of my age. The presence of that soldier under that tree made me feel secure, and his act of kindness towards the woman showed that he valued others more than himself. I compared this to the commander who had passed by the fleeing people in his jeep without offering help to those who were weak. This taught me that ordinary people can touch the lives of others in ways that those in power often do not.

Upon my grandmother’s return, I told her the events that had taken place and how the man had helped me feel safe. My grandmother spoke to the wounded soldier in our dialect to express her gratitude, but he did not understand due to his limited knowledge of the language. As my grandmother did not speak the locally spoken Juba Arabic, I helped her interpret her gratitude to the man. My grandmother then informed the man that she would take him to safety, but he initially refused, telling us to go ahead without him. However, my grandmother rejected his excuse, citing concerns over his lack of water and food. The little water that we had brought was not going to last long, and the man would certainly die. Even though he insisted that my grandmother take me to safety, she refused, determined to help him.

With a swollen leg and limping on one foot, the soldier came to my grandmother and told her that he was willing to walk with us. We started a slow but long walk towards the next township. Instead of following the main path, my grandmother told the man that we had to go into the mountains to find water. We walked slowly with some food baggage that my grandmother had managed to salvage when she went back. We slept one night on the way before we could reach the foot of the mountains and found a small spring of water. We made a camp with twigs and leaves to give us shelter.

My grandmother nursed that man and tended to his wounds every morning and evening. We ate wild fruits and plant tubers. We experimented with different leaves from known and unknown plants before boiling them. If, after a week, the leaves that we removed from a plant did not change its colour to yellow, or change colour, we did not eat them because it was considered poisonous. However, when the leaves changed colour, we boiled and ate them. We stayed at the foot of the mountains for about three months until the man was able to walk better again.

When it was time for us to leave the mountains and go to the next township, the man had conducted several secret observations of the town to ensure that the township was still in the hands of the SPLA. There had been a gun battle just two weeks before we left the mountains. When we observed that it was safe for us to go into the township, we entered at around noon. Early morning was not a good time, as we could easily be mistaken for enemies and fired upon. It was in that township that we separated from the man. He told us that he was going to find his family in another township.

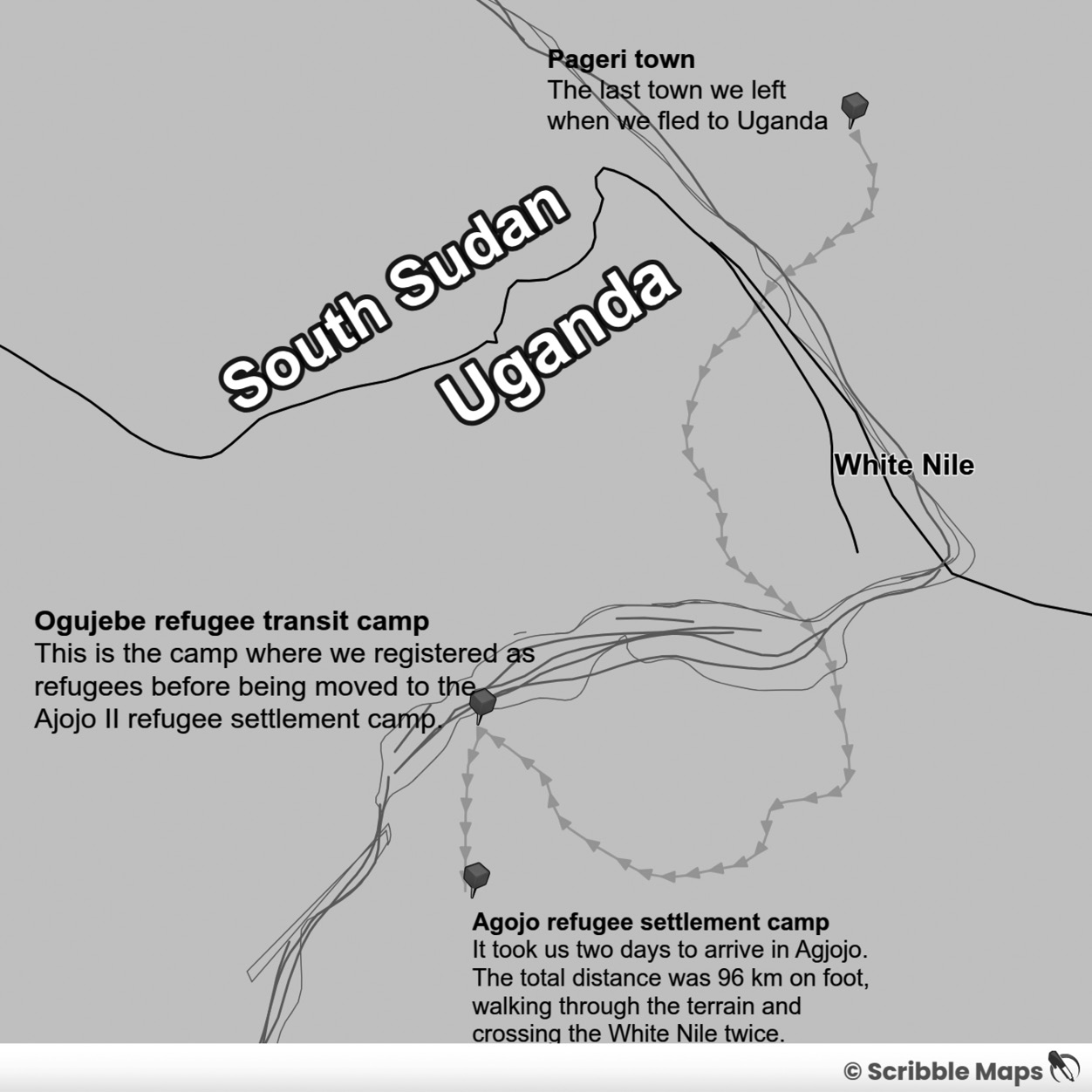

In December 1992, my grandmother and I fled to a refugee camp in Uganda. It took us three days to walk from Pageri to Agojo refugee settlement camp (see Figure 3). In the refugee camp, we were registered by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Ogujebe Settlement Camp and transported in a lorry to the Agojo refugee camp. In Agojo refugee camp, we were provided with basic items such as a tent, utensils, and emergency food. Life in the camp was vastly different from that which we had known in our homeland. Each person was given a piece of land measuring 5 m × 10 m to construct their own shelter. Unfortunately, we did not have any land to cultivate and grow our own food. People depended on food rations, which lasted only for some days. To conserve the little that was distributed, people ate food once a day and still ran out of food. It would be days before the next food rations were distributed.

Due to the lack of income for my grandmother and me, I took the initiative to gather papyrus reeds, weave them into mats, and sell them to generate some income. I ventured deep into the papyrus swamps along the River Nile near the Ogujebe refugee settlement camp to collect the reeds. Despite the weight of the bundles, I transported them to the shore, where I split and dried them before bringing them home to weave into mats. I continued doing this job every school holiday until I completed primary school. However, there were also other life challenges in the camp including limited access to clean water, proper sanitation, and necessities such as food and clothing. The lack of adequate living conditions led to a variety of health issues, including the spread of diseases and malnutrition. Malnutrition was prevalent in the camp, and communicable diseases and infections were a daily occurrence that often led to death.

Google map showing the routes we travelled on foot from Pageri to Agojo refugee settlement camp in Uganda

As a result of our conditions in the refugee camp, I frequently got sick with diarrhoea and malaria, lost significant weight and became extremely thin. One day, while I was sweeping our compound, my grandmother noticed a swelling on my knee. She thought I had tried to hide it from her. She called me over and asked with a weary voice, what had happened. I told her nothing was wrong. She pressed on the protruding skin, but I felt no sensation. It wasn’t a swelling, but rather my bone pushing against the skin. As I lay on the ground, she asked me if I felt any pain. I responded that I wasn’t feeling any pain, but I could hear the sorrow in her voice as she told me that my bones were protruding. Before this question from my grandmother, I had no idea I was wasting away. I began worrying about my health. I started to pay closer attention to my body, noticing that my ribs were all visible and my leg bones hardly had any flesh on them. It was difficult to determine just how much weight I had lost because everyone looked the same – skinny and malnourished.

Moreover, future uncertainty and the past trauma from witnessing conflict and violence to being displaced from our homes led to a profound impact on the mental and emotional well-being of many people in the camp. Many people who did not drink alcohol or smoke started doing so. Faced with prolonged uncertainty and limited educational opportunities, the issue of teenage pregnancies was particularly high among youths. However, despite these immense challenges, many young people, including me, exhibited remarkable resilience and strength to pursue a better life for themselves and their families, showcasing the enduring human spirit in the face of adversity.

I have recounted my personal experiences of growing up in a peaceful village in what was then Sudan, now South Sudan, and the circumstances that led to my becoming a refugee. I described the close-knit community, self-sufficiency, and daily life in the village, including farming, barter trade, and traditional practices. However, the arrival of the SPLA in 1986 abruptly disrupted our lives. I vividly remember the chaos and urgency as my family and villagers fled our village to escape the militia’s raid. Living through the war in our village was harrowing. My family endured constant danger and loss as armed militias terrorised our community. My father joined the SPLA to protect our village but tragically lost his life in battle, leaving me without a father figure. I was forced to take on adult responsibilities and was eventually taken captive during a conflict. Despite the hardships, I held on to the kindness shown by others during those difficult times. One poignant memory is that of fleeing with my grandmother from a township under attack. Our escape showcased acts of sacrifice and bravery, including my grandmother’s decision to retrieve a family heirloom despite the danger. Throughout the journey, the resilience and compassion of the civilians, especially towards the elderly, women, and children, were incredibly moving. These experiences captured the indomitable human spirit, and selflessness in the face of adversity.

In 1992, my grandmother and I fled to a refugee camp in Uganda, where we encountered numerous challenges such as food scarcity, health issues, and limited access to clean water and education. Despite these hardships, I persevered and pursued education, eventually moving to Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya for further opportunities. Kakuma camp, which was initially established for unaccompanied minors from Sudan, faced extreme weather conditions and environmental challenges. My personal account provides insight into the devastating impact of war and conflict on families and individuals. It sheds light on the challenges faced by a young person growing up without a father in a traditional society, as well as the resilience and determination exhibited in the face of extreme hardship. My journey from a peaceful village to becoming a refugee encompasses the profound impact of war, loss, and displacement, but also highlights the strength, and compassion found in the mid of adversity.