Human beings, who are almost unique in having the ability to learn from the experience of others, are also remarkable for their apparent disinclination to do so.

One of the greatest challenges in “doing” phenomenological research, in attempting to learn from the experiences of others, is figuring out just what to “do”. This appendix aims to encourage prospective hermeneutic researchers by offering, in its entirety, the method I developed to research the experiences of Irish university students with mental health difficulties presented in this book and elsewhere. It is offered in the spirit of open access, in response to the many kind emails from students and practitioners who get in touch to ask “how did you do it?”. This is not the hermeneutic phenomenological method, but rather a demonstration of how one phenomenological study, beginning from a point of deep engagement with the philosophy of hermeneutic phenomenology, proceeded to understand the experiences of one cohort within the higher education system.

This approach was inspired by a desire to understand lived experience and position the experiences of others as valuable a form of knowledge as the findings from the most rigorous scientific study. To do so required attending to four inter-related commitments:

1. A commitment to the philosophical principles of hermeneutic phenomenology;

2. A commitment to the ontological and epistemological integrity of the research approach;

3. A commitment to the trustworthiness of the data and process; and

4. A commitment to ethically sensitive research.

This appendix focuses on the second, third, and fourth of these commitments. It does so with the explicit assertion that the first, an understanding of the philosophical principles of hermeneutic phenomenology, is primordial and essential. Indeed, the most frequent criticism levied at phenomenological researchers is a lack of awareness of the philosophical foundations upon which this approach to research rests. A personal understanding of the philosophy of phenomenology means that a researcher, when faced with the many inevitable day-to-day research quandaries and decisions, responds to these in a way that upholds the integrity of the approach rather than reacts with “solutions” offered by other, sometimes opposing, approaches, methodologies, or methods. The philosophy of phenomenology, and the original texts of philosophers such as Husserl, Heidegger, Gadamer, Merleau-Ponty, and others, can initially appear intimidating and impenetrable to many, if not most, researchers. In an attempt to offer a handrail to guide first steps into this rich but often-intimidating philosophical domain, I wrote a paper, “Researching Lived Experience in Education: Misunderstood or Missed Opportunity” (Farrell, 2020), to which I brazenly refer interested researchers.

This appendix, in tun, will attend to (a) the ontological and epistemological assumptions, or paradigm, within which hermeneutic phenomenological research is conducted, (b) the method by which the data presented in this book were generated and analysed, (c) how the trustworthiness of these data were upheld and guaranteed, and (d) the measures implemented to ensure that the research was conducted and disseminated to the highest ethical standards. It will be organised by each accordingly:

1. paradigm

2. method

3. trustworthiness

4. ethical considerations.

The aspiration is to be clear and to offer practical insights into how the research was “done”. Again, this is just one hermeneutic phenomenological method, offered in the hope that it might guide, encourage, and offer some sense of direction to the perspective phenomenological researcher.

Bateson (Bateson, 1972, p. 320) argued all researchers are philosophers in that “universal sense in which all human beings […] are guided by highly abstract principles”. These principles include beliefs about ontology, or the nature of reality and what can be known about it; epistemology, or the relationship between the knower and what can be known; and methodology, or how the researcher can go about finding out what they believe can be known. Thus, one’s ontology directs our epistemology which in turn guides our methodology.

The living man is bound within a net of epistemological and ontological premises which – regardless of the ultimate truth or falsity – become partially self-validating.

This net, containing the researcher’s ontological, epistemological, and methodological premises, is often referred to as a paradigm (Guba, 1990). A researcher’s paradigm acts as a framework, or lens, through which we view a particular phenomenon. Paradigms are human constructions categorised by differences in beliefs about the nature of reality and knowledge construction. They are established by communities of scholars and as such can be neither proved nor disproved. There are a number of different research paradigms, the four major ones being positivist, postpositivist, interpretive, and critical social theory (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011).

Hermeneutic phenomenology is considered to sit within the interpretive paradigm. The interpretative paradigm evolved from the Heideggerian view of the nature of being-in-the-world and of humans as self-interpreting beings. Interpretivists study phenomena through the eyes of people in their lived situations with the ultimate goal of understanding. Benner (1994) highlights how interpretive inquiry is concerned with articulating, appreciating, and making visible the voices, concerns, and practices of those who are the focus of the inquiry.

The interpretive paradigms assumes a relative ontology (there are multiple realities), a subjectivist epistemology (knower and respondent co-create understandings), and a naturalistic (in the natural world) set of methodologies (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011). Ontologically, the interpretive paradigm is based on relativism, a view of truth as composed of multiple realities that can only be subjectively perceived. Epistemologically, interpretivists believe that knowledge is subjective; that there is no one ultimate or “correct” way of knowing. This epistemological view of knowledge as subjective has led some to consider interpretivism a paradox in that interpretivists attempt to develop an objective science from subjective experience (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011). Rainbow and Sullivan (1987) attest that this paradox is based on an objective-subjective split when, in fact, as Munhall (2012) points out, “objectivity is a subjective notion”.

Methodologies associated with the interpretive paradigm, reflecting both its relativist ontology and subjective epistemology, are united by an emphasis on the intersubjective construction of meaning and understanding. Knowledge is generated in interpretive research when “relevant insights emerge naturally through research-participant discourse” (Coffey and Atkinson, 1996, p. 54). Therefore, the researcher’s perspective is inextricably bound up within the findings of an interpretive inquiry. The interpretive paradigm views knowledge building as an inherently social act (the hermeneutic circle) and, as a result, methodologies within this paradigm tend to be qualitative.

While methodology (stemming from the Greek hodos meaning “way” and logos meaning “to study”) refers to “the pursuit of knowledge”, method (stemming from the Greek methodos) refers to the “mode” by which knowledge is pursued. The mode by which knowledge was pursued in this study forms the focus of the next section.

Some people speak of a method greedily, demandingly; what they want in work is method; to them it never seems rigorous enough, formal enough. Method becomes a Law … the invariable fact is that a work which constantly proclaims its will-to-method is ultimately sterile … [there is] no surer way to kill a piece of research and send it to join the great scrap heap of abandoned projects than Method.

Heidegger talked about phenomenological reflection as following certain woodland paths towards a “clearing” where something could be shown or revealed in its essential nature. These paths (methodos ), however, cannot be determined by fixed signposts, rather “they need to be discovered or invented as a response to the question at hand” (van Manen, 1990, p. 29). Indeed, it has been said that the method of hermeneutic phenomenology is that there is no method (Gadamer, 1979; Rorty, 1979).

What is offered here is the methodos by which the experiences of the students represented throughout this book were generated, analysed, and understood. It is not the method of hermeneutic phenomenology by any means, but just one method that might offer insights and points of reflection for other hermeneutic phenomenological researchers. I hope it is helpful.

The methodological point of departure for any study is its research question(s). These are especially important in hermeneutic phenomenological research where, in the necessary absence of a clearly delineated set of directions, they offer a guiding and welcome picture of the destination. Returning to these research questions, to this image of the destination, at regular intervals throughout the research journey helps ensure that the research stays on track.

This study was underpinned by two research questions:

1. What is the nature of the lived experience of students with mental health difficulties in higher education?

2. What meaning do these students ascribe to their experience?

Once established, these research questions also helped determine the what (nature and meaning of mental health difficulties), the who (university students with mental health difficulties), and the how (data generation and analysis) of the study. Each of these will be examined in turn, beginning with the sample (the what and the who) before turning to the method of data generation and analysis (the how).

According to Steeves (Steeves, 2000, p. 45), sampling “implies that a researcher is choosing informants because those informants might have something to say about an experience they share with others”. As a result, qualitative researchers typically, although not exclusively, employ non-probability sampling techniques. Non-probability sampling refers to a number of sampling strategies (e.g. convenience sampling, purposive sampling, opportunistic sampling, quota sampling, judgemental sampling, and snowball sampling). Non-probability sampling techniques, in contrast to probability sampling (the word probability deriving from the Latin probabilitas, a measure of authority or authoritativeness), do not aim to generate a sample representative of the entire population. Herein lies what many consider the major weakness of non-probability sampling.

Basically, non-probability samples are not samples at all but could be regarded as complete populations from which no statistical generalisations to larger populations can be made.

However, as the aim of qualitative research is to generate rich, contextually laden, explanatory data, it has little concern with generalisations or generating population-based estimates. Indeed, the relevance of generalisability to qualitative research has long been disputed, with transferability deemed a more appropriate measure of probabilitas (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Sandelowski, 1986). Research subjects in qualitative studies are selected, not because they increase the study’s p-value, but because they provide insight into the phenomenon under study.

Purposive sampling was the non-probability sampling strategy adopted for this study. Purposive sampling is based on the premise that study participants should be chosen based on the purpose of their involvement in the study. The strength and potency of purposive sampling, argues Quinn Patton (2002, p. 230), “lie in selecting information-rich cases for study in-depth […] those [cases] from which one can learn a great deal about issues of central importance to the purpose of the inquiry”. As the purpose of this study was to explore the lived experience of distress, direct experience of a mental health difficulty was an essential criterion for participation. The type or severity of mental health problem was not pertinent, nor was “expert” (e.g. psychiatrist or other mental health professional) validation or diagnosis. Hermeneutic phenomenology aims to understand subjective experience, and as distress is a highly subjective experience, it was considered futile to attempt to objectively categorise (i.e. via diagnoses, psychiatric classifications) this experience. However, by virtue of the majority of participants being recruited through university disability services, which, as discussed in Chapters 2 and 4, require a diagnosis as evidence of eligibility, the majority of the students in this study had received a diagnosis.

Sample size is often one of the most perplexing issues in hermeneutic phenomenological research. When Harry Wolcott (1994, p. 3) was asked “how many qualitative interviews is enough?” by a team of researchers from the British National Centre for Research Methods, he replied “the answer, as with all things qualitative, is ‘it depends’”. Phenomenological studies, however, tend to involve smaller sample sizes as these are more cost and time efficient and allow for greater focus on depth rather than breadth. Speaking about sample size, Quinn Patton suggests:

No rule of thumb exists to tell a researcher precisely how to focus a study. The extent to which a research or evaluation study is broad or narrow depends on purpose, the resources available, the time available, and the interests of those involved. In brief, these are not choices between good and bad but choices among alternatives, all of which have merit.

This research began with an anticipated sample size of 10–12 students. However, when an invitation was extended through three recruitment channels (youth mental health service and two university disability support services) the level of interest from students far exceeded expectations. It became clear that the opportunity to share their story rather than be “subjected” to a researcher-defined battery of questions, or survey, was of great interest to students. It was decided that, in line with the “open” principle of hermeneutic phenomenology, all students who would like to share their experiences should be offered the opportunity to participate (even if it did add a year to the research!). In total, 27 students shared their experiences as part of this study (Table 1).

Pseudonym |

Age |

Sex |

UG/PG |

Field of study* |

Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Adrianna |

22 |

F |

UG |

AHSS |

2 |

Alicia |

22 |

F |

UG |

AHSS |

1 |

Annie |

21 |

F |

UG |

AHSS |

2 |

Ashley |

22 |

F |

UG |

AHSS |

1 |

Claire |

20 |

F |

UG |

STEM |

1 |

Ella |

21 |

F |

UG |

AHSS |

1 |

Faye |

20 |

F |

UG |

Health Sciences |

1 |

Fiona |

19 |

F |

UG |

AHSS |

1 |

Greg |

29 |

M |

PG |

STEM |

1 |

J. D. |

20 |

M |

UG |

AHSS |

1 |

James |

26 |

M |

PG |

STEM |

1 |

John |

29 |

M |

UG |

AHSS |

1 |

Joseph |

43 |

M |

UG |

AHSS |

1 |

Kate |

27 |

F |

PG |

AHSS |

1 |

Kinsley |

21 |

M |

UG |

AHSS |

1 |

Lauren |

21 |

F |

UG |

AHSS |

1 |

Leon |

41 |

M |

UG |

AHSS |

1 |

Louise |

30 |

F |

UG |

Health Sciences |

2 |

Mai |

22 |

F |

UG |

Health Sciences |

1 |

Marie |

23 |

F |

UG |

STEM |

2 |

Mary |

26 |

F |

PG |

AHSS |

2 |

Millie |

19 |

F |

UG |

AHSS |

1 |

Niamh |

21 |

F |

PG |

AHSS |

1 |

Robert |

25 |

M |

UG |

AHSS |

1 |

Sarah |

26 |

F |

PG |

AHSS |

2 |

Sophie |

20 |

F |

UG |

AHSS |

2 |

Thomas |

19 |

M |

UG |

AHSS |

2 |

The genuine will to know calls for the spirit of generosity rather than for that of economy, for reverence rather than for subjugation, for the lens rather than for the hammer.

Data, stemming from the Latin datum meaning something “given” or “granted”, reflects the manner in which a hermeneutic phenomenological researcher is “given” an insight into another’s experience. However, as van Manen (1990) points out, experiential accounts are never identical to the lived experiences, rather transformations of those experiences:

So the upshot is that we need to find access to life’s living dimensions while realising that the meanings we bring to the surface from the depths of life’s oceans have already lost the natural quiver of their undisturbed existence.

The point of hermeneutic phenomenological data generation is to “borrow” other people’s experiences in order to form an understanding of the deeper meaning of an aspect of human experience. The data of other people’s experiences allows us to become more informed, shaped, and enriched, enabling us to render a fuller understanding of the phenomena in question. Hermeneutic phenomenological data may be generated using a number of techniques. These include conversational interviewing, eliciting written responses, participation observation, and oral or written biographies. However, the most commonly employed data generation technique in hermeneutic phenomenological research is conversational interviewing. Conversational interviewing is an effective means of exploring and gathering experiential narrative material with the aim of developing a richer and deeper understanding of a human phenomenon (van Manen, 1990). The conversational nature of hermeneutic phenomenological interviewing allows for what Bernstein (1991, p. 4) calls the “to-and-fro play of dialogue” with the ultimate aim of a “fusion of horizons’”(Gadamer, 1960/1989) between researcher and participant.

A total of 35 conversational interviews were carried out with 27 students. These ranged in duration from 40 minutes (for a second interview) to 90 minutes, with an average of just over an hour. Those students who expressed interest in participating were provided with detailed information about the study and the opportunity to ask any questions that they might have. At this stage, if the student was happy to proceed, a date and time for the first interview was arranged. The student was met in a public place and walked to a quiet room in which the interview was to take place. This offered an opportunity to chat to the student more informally and, hopefully, put them at ease, plus overcome the intimidating prospect of expecting the student to find a small, third-floor room in a large, unfamiliar building. Once settled in the quiet interview room, the aims of the study would be reiterated, with a particular emphasis on how the study was very much about understanding the student’s experience, that there were no right or wrong answers, and that what was important was whatever was important to the student themselves. The consent form was discussed and the students invited to ask any questions before signing the consent form. At this point the digital recorder was turned on.

Each interview was guided by just one question – can you tell me a little about yourself and your experience? From here the student would typically begin by describing themselves, what they were studying and a little about their family/living situation. However, often within the first five minutes, the student would begin to settle in, open up, and share their story – the story of their experience of “it” (whatever “it” happened to be). Interviews typically lasted between 60 and 90 minutes, with most conversations drawing to a close naturally at about the 60-minute mark. It was my responsibility, as researcher, to guide the student back – re-orienting them to the present by asking about their plans for the rest of the day or chatting casually about upcoming assignments or plans for mid-term break. It was an opportunity to check in and ask how they were after our conversation and reiterate the support available to them by virtue of participation in the study, if they needed it. Directly after the interview, I would make notes in the field journal. These would often be added to later in the day, and sometimes in the days following the interview, as new thoughts, ideas, and reflections came to mind.

A follow-up email was sent to every student the evening after their interview. Each was personalised, expressing the appreciation and enormous respect felt towards the participant. It was outlined that, sometimes after going back over such deeply personal issues, the student might feel vulnerable and, if they were at all concerned, the student was encouraged to get in touch and additional support could be provided if necessary. For students who only did one interview, they were invited to stay in touch and were reminded that they would be updated about the research at various points throughout its life course. For students taking part in a second interview, the process above was repeated a second time

The conversational interviews themselves were just that – conversational. The experience, as researcher, of walking into a room to meet a stranger without an interview schedule or any sense of how things were going to unfold, was intimidating, to say the least. It offered a sense of how reassuring a clipboard with a series of guiding questions could be and how, particularly during the first few interviews, a lack of clear structure meant that every interview was a journey into the great unknown. However, the lack of structure proved to be one of this approach’s greatest offerings in that it created space for the student to take the researcher through their experiences, thoughts, and feelings without these being curtailed or restricted by the pre-ordained conventions of an interview schedule or hypothesis-driven agenda.

My task as research was to simply initiate the conversation with the question above (can you tell me a little about yourself and your experience?) and interject only when (a) I didn’t quite understand something and needed clarification, (b) when trains of thought or conversation slowed or appeared to come to a halt and needed to be restarted and, (c) from time to time, to gently steer the focus back to what it was actually like (lived experience) and rather than getting overly caught up in the “and then this happened”. Prior to almost every interview I was worried that, without the handrail of a series of pre-prepared questions, the conversation would fall flat. However, time and again I was astonished at how much students wanted to share, and how much they thrived upon the opportunity to tell their story in their own words, in their own way, and in their own time. The richness and complexity captured in the data presented in this book and in other publications from this research bears testimony to this.

The check-in emails sent to each student after every interview had a two-fold intent – to thank them for giving so much during the interview and to check that it hadn’t taken too much out of them or brought any difficult feelings or memories back to the surface. However, it also offered them an opportunity to feed back, not only how they were doing, but how they found the experience overall. The following feedback, offered by Niamh, reflected the student’s appreciation not only of the approach and its value in informing responses to mental health issues, but the opportunity to be empathically and respectfully listened to.

I haven’t really ever opened up or talked in depth about those experiences since therapy a few years ago. It was incredibly emotional for me I guess but a huge satisfaction came from it especially today I feel like a weight off my shoulders. It’s an honour to talk to someone so incredibly empathetic and a great listener and I hope it will help your research and it will future allow other professionals in the mental health care services that peoples experiences have such a huge richness and so much can come from it. I admire the approach you have taken and the time and effort it takes.

A total of 36 hours of audio was recorded over the course of the 35 conversational interviews, and this yielded, when transcribed verbatim, 997 pages of written data. The next step was to analyse these data.

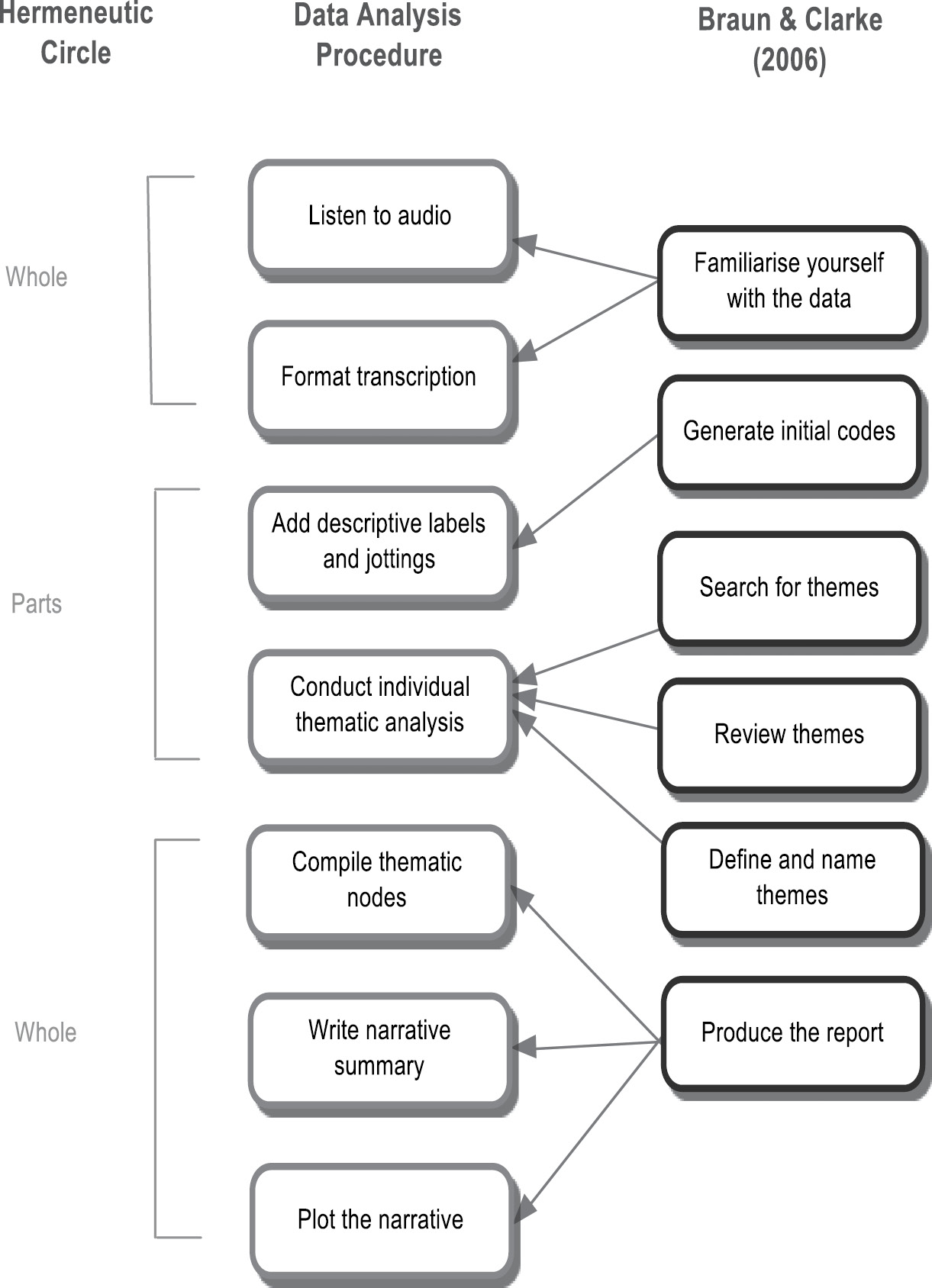

Perhaps the greatest challenge in adopting a philosophical approach such as hermeneutic phenomenology is translating its often complex philosophical concepts into methodological techniques. Indeed, as Roberts and Taylor (1998, p. 109) have noted, “many of the so-called phenomenological methods leave prospective researchers wondering just what to do”. In attempting to overcome this challenge, data generated over the course of this study were analysed using a combination of the principles of the hermeneutic circle and the methodological framework for thematic analysis offered by Braun and Clarke (2006).

The concept of the hermeneutic circle can be viewed from both ontological and methodological perspectives. Heidegger and Gadamer both viewed the circularity of interpretation not so much as a methodological principle, but as a ubiquitous and inescapable feature of all human efforts to understand. As such there is no method, experience, or meaning that is independent of the hermeneutic circle. Moreover, all efforts to interpret or understand are always located within some background (e.g. socio-historical tradition, value system, or practice) that cannot be ignored. Prior to generating and analysing the data, time was devoted to explicating this background (a significantly abridged version of this explication can be seen in Chapters 1 and 2).

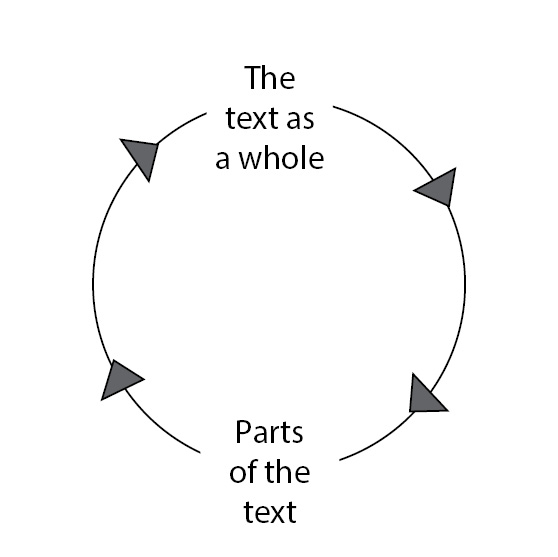

The hermeneutic circle is essentially based on the idea that understanding the meaning of a text as a whole involves making sense of the parts, and grasping the meaning of the parts depends on having some sense of the whole. As such, interpretive understanding goes forward in stages, with continual movement between the parts and the whole allowing understanding to be enlarged and deepened.

The hermeneutic circle as method of interpretation.

The hermeneutic circle, by its very circular nature, suggests that the meaning of a text is not something that can grasped once and for all. Meaning exists in a complex interplay between parts and whole. Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step process of data analysis provided a flexible framework for analysing the “parts” as well as the “whole” of the text. It is a framework that enjoys “theoretical freedom” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 5) in that it is applicable across a range of epistemological and theoretical approaches without impeding on the particular values of an approach such as hermeneutic phenomenology. As Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 4) themselves acknowledge, “one of the benefits of thematic analysis is its flexibility”. As such, it is a methodological framework that can be adapted to align more closely with the approach taken. Figure 2 outlines the relationship between the data analysis procedure employed in this study, Braun and Clarke’s (2006) method of thematic analysis, and the hermeneutic circle itself.

Relationship between individual data analysis procedure, hermeneutic circle and Braun and Clarke’s (2006) method of thematic analysis.

The steps taken to analyse the data in this study were as follows.

1. Listen to audio. Each interview was listened to and transcribed verbatim.

2. Format transcription. Each interview was listened to a second time, checked for accuracy, and the transcripts formatted for analysis. This simply involved coping the data from the masterfile into a new document, increasing the line spacing and adding a wide margin on one side for the descriptive labels and jottings below.

3. Add descriptive labels and jottings. Each interview was listened to for a third time and descriptive labels and jottings were added to a margin constructed along the side of the transcript. This was the point at which content and themes began to be noted and a sense of what the dataset reveals overall began to form. The labels and jottings at this stage mainly comprised striking quotations or words used by the students. This helped ensure the labelling process remained as true to the students’ own words as possible.

4. Conduct individual thematic analysis . Each individual student’s data set was analysed thematically. This step enveloped three of Braun and Clarke’s methodological steps (as seen in Figure 2). It also marked the step where the data began to be “transformed” (Wolcott, 1994). This transformation involved actively uncovering themes or, as van Manen (1990, p. 90) describes them, “knots in the webs of our experiences, around which certain lived experiences are spun and thus lived through as meaningful wholes”. A theme, according to Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 82), “captures something important about the data in relation to the research question, and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set”. This individual level of analysis continued for each student and, once completed, was followed by a “stepping back” and taking stock of all of the themes or thematic nodes generated.

5. Compile thematic nodes. Each of the 331 thematic nodes generated by phases 1–4 was written on individual strips of card with the student’s pseudonym written on the back. Each piece of card was then laid out, organised, and collapsed under thematic headings. For example, “‘picked on’ by teachers” (Mai), “Bullying” (Marie, Ella, Niamh, J. D., Sophie), and “Dyslexia” (J. D., Sarah) were all themes relating to issues that students described affecting their early school experiences and so were collapsed under the thematic heading of “Difficulties in School”. Significant time and thought were dedicated to this organising and compiling, and the sounding board of a “critical friend” (see trustworthiness section below) was particularly helpful in this process.

6. Write the narrative summary offered the opportunity to step back and review the “whole”. It involved writing a “narrative summary” of each student’s story that was both temporal and thematic, that is, it told their story, as they described it unfolding, and ensured that the major themes identified in earlier phases were represented in this chronological telling. The anonymised narrative summaries of each of the 27 participants were presented as an appendix in the final report. During the data generation process, and particularly in the early stages of data analysis, a structure began to emerge from the students’ narratives. It became clear that the students themselves, when given freedom and space to tell their story in their own words, did so in a particular way. Their stories followed a “plot”. Step seven involved plotting this narrative for each student.

7. Plot the narrative . While the plotting of the initial stories began as an exercise in curiosity, it became clear that this structure was revealing something very important about the way in which the students were making sense of their experiences. It revealed the narrative meaning that the students had ascribed to their experiences and, as the same structure emerged in dataset after dataset, the plotting of narrative became not only an integral part of the data analysis process but a unique way of viewing each dataset, both in terms of its “parts” and its “whole”. These plots can be seen in Farrell (2022b).

This process of analysis yielded:

1. 27 narrative summaries

2. 46 themes (i.e. the nature of the lived experience)

3. A four-phase plot which offered an insight into how students organised their experiences into meaningful wholes (i.e. meaning).

At every stage of the research process, measures were taken to uphold the validity or trustworthiness of the data and to ensure that the research was conducted to the highest ethical standards. These measures form the focus of the remainder of this methodological appendix.

Up until the late twentieth century, social science researchers had developed a certain degree of consensus about what counted as knowledge and, more importantly, what kind of knowledge claims could be validated. However, the “narrative turn”, which occurred towards the end of the century, posited a challenge to conventional forms of evidence. Researchers steering the narrative turn, which Polkinghorne (2007, p. 472) collectively refers to as “reformists”, argued that personal descriptions of life experiences offered knowledge about important, but often neglected, aspects of the human realm. The pre-existing group, which Polkinghorne (2007, p. 472) refers to as “conventionalists”, struggled to accept this new movement. Their dismissal of the claims generated by this form of research was largely justified by the failure of the claims to withstand conventional measures of validity.

Typically, the issue of validity is approached by applying one’s own community’s protocols about what, in its view, is acceptable evidence and appropriate analysis to the other community’s research. In these cases the usual conclusion is that the other community’s research is lacking in support for its knowledge claims.

In response, researchers, such as Lincoln and Guba (1985), took conventional criteria for establishing the “trustworthiness” of claims and developed parallel criteria for more qualitative research approaches. These criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability will structure the discussion around this study’s efforts to uphold standards of rigour and trustworthiness. Table 2 provides a visual overview of conventional measures of validity, Lincoln and Guba’s (Lincoln and Guba, 1985) parallel criteria for qualitative research, and the measures taken to uphold and demonstrate efforts to ensure that the data, interpretations, and claims espoused in this study are, in so far as it is possible, trustworthy.

Scientific paradigm criteria |

Measures taken |

||

|---|---|---|---|

Truth values |

Internal validity |

Credibility |

✓ “Phenomenological nod” ✓ Critical friend ✓ Field journal |

Applicability |

External validity |

Transferability |

✓ Narrative summaries ✓ Sample transcript and analysed outputs from this transcript ✓ Critical friend |

Consistency |

Reliability |

Dependability |

✓ Overview of approach taken ✓ Explication of researcher’s bias ✓ Outline of methodology |

Neutrality |

Objectivity |

Confirmability |

|

✓ Audit trail ✓ Direct quotations ✓ Critical friend report ✓ Sample transcript and analysed outputs from this transcript |

The term “credibility” is used to represent the truth value of the research. Lincoln and Guba (1985) claim that a study is credible when it presents such faithful descriptions that when co-researchers or readers are confronted with the interview transcriptions they recognise the thematic conclusions. The Dutch phenomenologist Buytendijk referred to the “phenomenological nod” as a way of indicating that a credible phenomenological description is something we can nod to, recognising it as an experience that we have had or could have had (van Manen, 1990). In order to ensure that all conclusions arrived at in the current research are firmly grounded in the data, a random selection (n=4) of interviews – their recordings, transcripts, thematic analyses, narrative summaries, and plots – were read and assessed by a “critical friend”. With a background in philosophical criticality, the critical friend was well poised to assess the credibility and truth value of the data analysis. According to Koch (1994), credibility in hermeneutic phenomenology is enhanced when researchers describe and interpret their experience as researchers. She believes self-awareness to be essential and recommends researchers keep a journal “in which the content and process of interactions are noted, including reactions to various events” (Koch, 1994, p. 92). A detailed field journal was maintained throughout the data generation, analysis, and “write up” phases of this research project. Comprising of two full Moleskine notebooks, the field journal(s) offered a space to record details around the data generation process, my own reflection on the experience of engaging in the “to-and-fro” of each conversational interview, and any instances my own pre-judgements or prejudice may have bubbled to the surface. It also offered a space to consider the identification of themes in the analysis process and the many factors that may have resulted in “seeing” some themes and not others.

The applicability of conventional social science research is assessed by how well threats to external validity have been managed. These threats include anything that may interfere with a study’s ability to produce claims about cause-and-effect relationships that are generalisable to populations. Reformist approaches, in contrast, believe generalisability itself to be somewhat of an illusion and focus, not on cause-and-effect relationships, but on understanding human experiences. Guba and Lincoln (1985) suggest that the applicability of such research is better established by its transferability or “fittingness” into similar contexts.

A study meets the criterion of fittingness when its findings can “fit” into contexts outside the study situation and when its audience views its findings as meaningful and applicable in terms of their own experiences. In addition the findings of the study, whether in the form of description, explanation, or theory, “fit” the data from which they are derived.

Contextual information is essential if a reader is to assess whether findings “fit” into particular contexts. Accordingly, the reader was provided a detailed narrative summary which provided contextual information, not only on the student and their story, but on the process by which the story was generated and analysed. Moreover, a full transcript was provided so that the reader was able to read a verbatim account of an interview and determine if the interpretations of this data, presented in the narrative summary and in the findings relating to that particular student, “fit” with the data from which they are drawn. The critical friend had an opportunity to do this with four full transcripts and their appraisal of transferability was included in the final report.

There is no neutrality. There is only greater or less awareness of one’s biases.

The consistency and neutrality of an inquiry, sometimes spoken of in terms of “reliability” and “objectivity”, refer to the degree to which various readers or researchers may arrive at comparable, but not contradictory, conclusions given the same data (dependability), as well as the degree to which the conclusions may be confirmed by the data (confirmability). Lincoln and Guba (1985) suggest that both dependability and confirmability are best assessed based on the study’s “auditability”.

Essentially an auditor called in to authenticate the accounts of a business or industry is expected to perform two tasks. First, he or she examines the process by which the accounts were kept, to satisfy stakeholders that they are not the victims of what is sometimes called “creative accounting” […]. The second task of the auditor is to examine the product – the records – from the point of view of their accuracy.

Just as a fiscal auditor should have access to details of the process, the inquiry auditor, or reader, should have access to the details of the process by which the product – the data, findings, interpretations, and claims – was developed. The final report included details of the approach itself, an exposition of my own prejudice, as well as an audit trail detailing the sampling strategy and data generation and analysis processes. The reader was also offered an opportunity to examine the accuracy of the “product” in a number of ways. These included (a) the use of direct quotations, complete with reference to the page of transcript from which they were taken, (b) the critical friend report which provided an outsider assessment of the dependability and confirmability of four, randomly selected, transcripts and their outputs, and (c) access to one complete transcript, its initial analysis, the thematic conclusions drawn, and the manner in which the student’s story was “plotted” onto the narrative structure than emerged in the study.

In being able to assess the process of the inquiry, the reader was able to attest to its dependability (Table 2). Equally, in examining the product, the reader was able to confirm the degree to which the product is supported by the data. As such, auditability offers a means of assessing both the dependability and confirmablity of the study (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). Research cannot be considered trustworthy, that is, credible, transferable, dependable, and confirmable, unless it is, in the first instance, ethical.

Hermeneutic phenomenological research methods, such as conversational interviewing, typically require the researcher to enter the participant’s lifeworld and access their lived experience (Polit and Hungler, 1999). This intrusion into the private sphere means that hermeneutic phenomenological research is categorised as “sensitive” research. Consequently, ethical considerations are of great importance in research adopting a hermeneutic phenomenological approach, particularly this study which sought to access the lived experience of psychological distress. Gaining ethical approval is at the heart of all research, particularly sensitive research. Accordingly, this study necessitated, and was successfully awarded, ethical approval from the ethics committees of the two universities and one mental health service from which students were recruited.

This research was underpinned by two main ethical principles: informed consent and confidentiality.

1. Informed consent is the principle that participants should not be coerced or pressured into research against their will, but that their participation should be based on voluntarism and with full understanding of the implications of participation. Informed consent has been the cornerstone of ethical guidelines since the Nuremberg Code – a code established as a result of the atrocities carried out by medical professionals during the Second World War. Students who volunteered to participate in this study were informed about the aims of this research, what participation would entail, and their rights as participants in a number of ways. They were provided with a copy of the consent form and given time to read this in advance of the initial interview. The interview itself began with a verbal reiteration of the study’s aims and the students’ rights, as well as an opportunity to ask any questions, before the student completed and signed the informed consent form.

2. Confidentiality: The Declaration of Helsinki which outlines the ethical principles of medical research, added confidentiality and privacy to the Nuremberg Code. Confidentiality means not disclosing information gained from research in other settings, such as everyday informal conversation. It also relates to the protection of the identity of participants and sites in published accounts of the research. Participant confidentiality was a significant factor in this study – one that was taken very seriously. The only instance in which confidentiality would have been breached was in the event that participants were deemed to be at immediate risk of harming themselves or others. This was in line with standard ethical practice in mental health research (Psychological Society of Ireland, 2011) and participants were made fully aware of this limit to confidentiality verbally, in the information sheet and in the consent form which they were asked to sign before the first interview. Thankfully, this did not emerge as an issue at any stage throughout the study but if it had a protocol was in place at all times to ensure the researcher could access additional supports for the students if necessary. Anonymity was an important aspect of confidentiality. Students were asked to choose their own pseudonym – a name that they liked and felt represented them without making them in any way identifiable. Other distinguishing features such as names, places, courses of study, or events that would be considered usual or likely to make the student identifiable were altered to protect the student’s identity.

In addition to these two cornerstones of ethical research, Beauchamp and Childers (2001) outline a number of moral principles upon which ethical research practice is based. These are:

Respect for autonomy: respecting an individual’s right to make decisions and enabling them to make reasoned informed choices.

Respect for autonomy means respecting the participants’ freedom to decide what to do. This particularly relates to the students’ right to withdraw at any time without having to offer a reason. As already outlined, students were informed about their rights as participants in a number of ways – the participant information sheet, verbally at their first interview, and again in the consent form where they were required to tick boxes to confirm that they understood what was being asked of them and their rights as participants (including the right to withdraw at any time without giving a reason). Moreover, respect was one of the strongest values underpinning this research and respect for the student, and the stories they shared, extended far beyond the data generation process to every aspect of the analysis, write up, and dissemination phases.

Beneficence: seeking to achieve the best balance between risk and benefit that achieves the greatest benefits for the individual.

This study sought to capture the unique insight and expertise of those with lived experience of psychological distress so as to better understand the experience. At the outset, it wasn’t clear whether the participant would see any personal benefit in participating in the study. In addition, there was concern that participation might result in the student revisiting painful experience which may be distressing for them. However, as the data generation process unfolded it became clear that participating in this research offered students a rare opportunity to be listened to; to be truly heard for what they had to say without being interrupted or corrected; and for their perspectives and insights to be held as valuable sources of knowledge. In addition, students spoke about how much they wished to share their experiences in the hope that it might one day help someone else in a similar situation. It appears that these two, largely unforeseen, aspects of participation meant that sharing their stories as part of the research was a worthwhile and even “cathartic” (Kinsley – follow-up email) experience for the students.

I would feel so happy if I could help even one person out there to avoid the mistakes I made growing up … I was unlucky but through modern research I’m hoping that other people do not have to suffer like I did.

Justice: addressing issues fairly for individuals in the same or similar situation.

This study viewed the phenomenon of psychological distress, to borrow Marcel’s (1950) sentiment, not as a problem in need of a solution but a mystery in need of evocative comprehension. It does not seek justice or to unravel a problem, rather to achieve a direct contact with the world of living with psychological distress. In this sense, the present study sought to “do justice” to participants’ lived experiences rather than result in justice for participants and those in a similar situation.

Non-maleficence: avoiding causing harm.

The protection of those who participated in this study was of utmost concern. This concern extended beyond the important ethical aspects associated with the data generation process, to the protection of the students accounts, and the integrity with which these stories were treated during analysis, presentation, and dissemination.

The ability to learn from the experiences of others, as Adams suggests at the beginning of this appendix, presents one of the greatest opportunities available to us as human beings. Hermeneutic phenomenology represents a powerful way of understanding lived experience. However, many prospective hermeneutic phenomenological researchers struggle to find an entry point into the complex philosophy of phenomenology; to align the ontological, epistemological, and methodological orientations of the approach; to demonstrate the trustworthiness or validity of the research; and to know that they have considered all possible ethical requirements. I hope that prospective hermeneutic phenomenological researchers will be reassured, even encouraged, in reviewing this one attempt to research lived experience. I wish you well.